‘But how on earth could he disappear into thin air?’

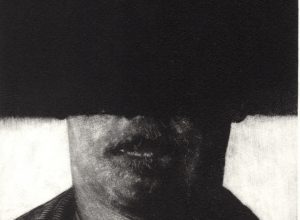

I could barely see the detective’s mouth move because his mustache was hung all the way down to his bottom lip. He scanned the room with eyes that looked as if they had seen more alcohol than violence.

It had been a week since my father’s disappearance. Mother had stopped crying. My brother looked mostly absentminded. The extended family who had come to support us during this time of crisis were mostly bored. The detective was the only person standing in the room, his back to the fireplace. The flames behind him so large that it looked as if he had just leaped out of them.

‘Let’s take it from the beginning’, he said again. ‘Another normal day, children back from school by 3.45 p.m. Mr Silk writing all day in his writing chamber.’

Father’s writing chamber was an old, dry well at the bottom of the garden. Three years earlier, he had turned it into his workplace. A strange choice of office, but it was only down this secluded well that my father found peace; a place to hide and write, away from a world that didn’t understand his passion or care much about it.

‘At about 6;30 pm, Mr Silk returned to the house for a brief meeting with a film director. Dinner was at 8 pm, and Mr Silk was his quiet, content self. After dinner he sat for a short while before the fireplace, then retired to his writing chamber. The last time anyone saw him was at 10:30 pm.’

The detective paused. Someone yawned.

‘At 10 am the next day, Mr Silk’s daughter went to the writing chamber with his black coffee.’

I was the only one allowed in father’s writing chamber. It was a special honour, but in truth, no one else was ever curious enough to bother. The first time I went down the wooden ladder, I thought it would perhaps be like Alice’s rabbit hole. However, it was a tiny office room crammed top to bottom with books, with a plain wooden desk and a chair with a high back, and a long thin bench with a padded cushion where father took his naps. I wondered how this cramped place with no windows might inspire him, until I looked up and saw a starry sky, midnight blue and twinkling, as if seen through a telescope. ‘Wow. This is magical, Father. It feels so out of this earth.’

The detective turned to me. A lock of hair fell straight across my face, obscuring one eye. He looked straight into the other eye.

‘Well Miss, was there anything unusual or out of place when you went to your

father’s writing chamber? A note perhaps?’

He addressed my eye. I thought he would ask me to tie my hair back so that he could stare into both eyes, but he didn’t. I was grateful. It was easier to keep a steady glance when only one eye was looking.

‘Nothing,’ I replied.

Across the room relatives were nodding off. ‘I’ll be leaving now,’ he said. ‘But I’ll be back again.’ He slipped his fountain pen into his breast pocket and strode out the room.

Days folded into weeks. Nothing. My aunts and uncles all left. At first the detective returned often to our living room to stand before the fireplace and interrogate my one visible eye. He asked to search father’s writing chamber. He traced his steps from the house to the well and back. He took notes. But nothing brought him any closer to unraveling the mystery of my father’s disappearance. The weeks became months. The detective stopped coming. The case was inevitably closed. The writing chamber was emptied, the well sealed off. The young girl that I was, grew up without her father. She read the many books from his library. She wrote. She painted midnight skies as if seen from the bottom of a well. All the while she hoped that through his disappearance without a trace, her father had found his purpose.

Forty years later

I knocked, and the door opened to a pair of old, familiar eyes that looked as if they’d seen much alcohol and no violence. He had a walking stick in his left hand. Time had not been kind to him. I wondered if he still saw in me, now plump and greying, the 15-year-old girl who certainly knew more about her father’s mysterious disappearance than she had made out. We stood for a moment staring at each other. It was the first time he had seen both my eyes.

‘Hello,’ he finally said. His mustache had thinned. It was neatly clipped. It was my first time to see words forming on his lips.

The room beyond the entrance was huge, but swallowed up by many people, talking, drinking, smoking. Music and laughter, a blur of faces, their backs to a blazing fireplace. Someone walked in with a huge chocolate cake with many lit candles. Someone broke into song.

‘Happy Birthday,’ I said with a smile. The detective smiled back.

‘Don’t you think a gift is due?’

I nodded.

‘It certainly is. Let’s find a quiet spot. This is to be a very important gift.’

I handed him a small brown parcel. He clutched it and led me away from the noisy gathering, down a dark passageway to a small study, reminiscent of my father’s writing chamber, only this one didn’t have a skylight, just an enormous window overlooking the sea.

‘I’ll probably die soon,’ he said.

I couldn’t disagree.

‘Yes. You probably will. I’m sorry I couldn’t find you sooner. Now that I have, I think you should know more about that case you investigated so long ago.”

‘Ah yes! The mysterious case of the disappearing Mr Silk. I knew all along that you were hiding something.”

He sighed and turned to face the sea. Alcohol, unsolved mysteries, and the deep blue waves reflected in his eyes. Slowly he unwrapped the parcel.

‘A book? Out of Earth, by J.D. Silk!’

He opened it, and a note, brown with age and coffee stains, fluttered to his feet.

‘But the pages are all blank,’ he said with a frown. ‘I don’t understand… What’s this all about?’

I smiled wistfully and bent to pick up the note.

‘That day when I brought my father his coffee, I saw nothing unusual. But he wasn’t there. Then I found this note on his desk. He left it for me.’

I handed it to him. He held it close to his face and began to read aloud:

‘Do not worry about me. I have gone to create a work of art. Read the reverse and you will understand.’

He turned it over and read on–a quote from E.M. Forster I had long since memorized:

‘What about the creative state? In it a man is taken out of himself. He lets down as it were, a bucket into his subconscious, and draws up something which is normally beyond his reach. He mixes this thing with his normal experience, and out of the mixture he makes a work of art… And when the process is over, when the picture or symphony or lyric or novel (or whatever it is) is complete, the artist, looking back on it, will wonder how on earth he did it. And indeed he did not do it on earth.’

Artwork courtesy of Youssef ElNahas