The call came before the sun. Teresa walked over to the stove clutching the old, corded phone to her ear. She turned off the fire warming a pan of milk for her coffee.

“You’re mistaken,” she said to the woman who’d called, blinking away the cobwebs of sleep that clung to her eyes.

“I’m so sorry to have to say this over the phone, ma’am,” the woman, Beverly, said.

“Overdose?” Teresa asked. “Caridad?”

“The ID says Carima.”

Teresa rested her palm on the cool tile of the kitchen counter to steady herself. She closed her eyes. Caridad, who left home fifteen years prior, swathed in layers of black from head to toe telling Teresa, “I’m Carima now.”

“How did this happen?” Teresa asked Beverly.

“I’m sorry, ma’am. I know very little. She wasn’t in our system; there had been no complaints. We got a call from a neighbor and went to investigate and found her there.”

“I just—I don’t understand.”

“I know. I’m so terribly sorry. This is tragic. For you and for your granddaughter.”

“Granddaughter?” Beverly’s breath hitched.

“Oh,” she said. “You didn’t know. My God. Yes, Carima has–had–a daughter, and you are listed as next of kin.”

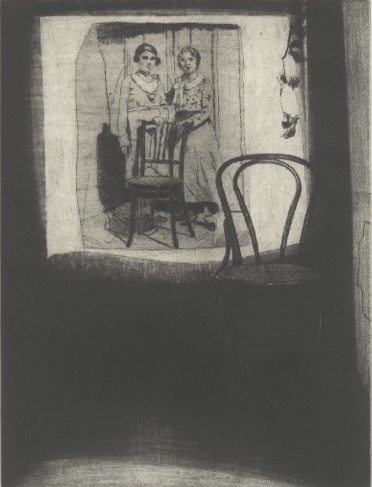

Teresa was numbed by shock. Her daughter who she’d not seen nor heard from in fifteen years was dead, a granddaughter she didn’t know existed. And, despite the years, next of kin – her daughter hadn’t written her completely out of her life. She hung up the phone and sat at her kitchen table, laying her face in her palms as a flood of hot grief rushed in.

They’d always fought, or Caridad at least. What was wrong with the name Caridad? Teresa had asked when her daughter came home in her headscarf and long dress all those years ago. It was a good name, Teresa had insisted, a name of Our Lady. Why couldn’t her daughter appreciate that?

“Because I’m a Muslim now. I’ve changed. Some of us can open our minds and change,” Caridad had responded, her voice and her face as hard as ever. Religion, rather than softening her, only seemed to sharpen her edges.

Teresa had sighed and shook her head. Her daughter had always been so defiant, refusing to take communion, refusing church altogether. Complaining the priests were racist, arguing viciously that Teresa admit they were Black.

“Nosotros somos mestizas,” Teresa had insisted.

“Mestiza is anti-Black bullshit, Mami,” Caridad had snapped. “Look at our hair,” she’d said, fluffing out her thick black coils. “Look at our skin. Somos negras, Mami. It doesn’t make us less Mexican than anyone else. I won’t be ashamed even if you are.”

Caridad who was always fighting, always angry, at least with Teresa.

“Why don’t you go anywhere, Mami? Why don’t you do anything with your life?” she’d once asked.

“What are you talking about?” Teresa had responded. “I work. I go to church. I take care of you.”

“You call that living?” Caridad had scoffed. “Soon as I can I’m leaving this place and I’m never coming back.”

Perhaps that was what this new religion had meant to her, a broader horizon, a bigger life. Teresa would never know. She had never found a way of getting through to her daughter. Now she was gone forever with an orphaned twelve-year-old daughter needing to be claimed.

Teresa, who had never left New Mexico, rarely even Gallup, needed to fly to Los Angeles. She requested a week off from her job at the pharmacy, her first time ever. “Good for you,” her boss had said, assuming Teresa was finally taking a vacation.

Nina from church who chewed bubble gum incessantly and kept her nails long and pointed like knives, brought over her laptop one evening to help Teresa buy a plane ticket. Los Ángeles. Ciudad de los ángeles. It was a sign, Teresa thought.

“This place, it sounds nice,” she said to Nina as she peered over the woman’s shoulder at her bright screen, her heavy scent of vanilla body spray making Teresa’s eyes water.

Nina turned around to look at Teresa, her doll bright eyes wide behind thick black eyeliner and false lashes, jaw bulging with gum that popped like small firecrackers in her mouth. She blew out a halfhearted bubble then sucked it back in, staring at Teresa.

“I’ll bring you to the airport,” she said.

“Ma-ree-yam,” Teresa pronounced, stretching out the syllables.

“Mariam,” the girl responded, pulling them back together.

Her skin was coffee with only a few drops of milk, coarse hair pulled back with a hot pink elastic. A man-sized white t-shirt revealing fragile collarbones and a hint of a baby blue bra strap, jeans faded at the knee, scuffed pink jelly sandals. Teresa lingered back to the girl’s hair; her fingers itched thinking about combing it.

She had envisioned skin the color of dulce de leche and hair in tight spirals, eyes deep wells threatening to overflow, beseeching her for help, for love. The eyes that greeted her were sullen, distrustful, Caridad’s. But the name sent a warm tingle that spread out from the center of her chest. Mariam. María. Our Lady, returned.

Back in her home, safe in her four walls, Teresa could breathe. Days after her flight, she still shuddered. She’d seen majestic palm trees so tall they seemed to touch the heavens, but far down below, where her daughter had ended up, God’s angels had departed long ago. Teresa wanted to wash her mind of what she had seen, instead she looked to the sky outside her living room window, its infinite blue, wide open.

10 a.m., the girl was still asleep. Teresa crept past the closed door, then walked, then opened and closed doors. Nothing. She could hear the girl breathing, soft purrs of deep sleep. Let her rest, Beverly had insisted.

“She’s had a tough early life,” she’d said as they sat in her office in Los Angeles. “She’ll need counseling. Lots of space and, when she’s ready, lots of love.”

Space, Teresa thought on her fifth cycle of pacing, counting the steps from the back of the house to the front. Not many, not enough, two bedrooms, cramped living room, a whisper of a bathroom. When Caridad left, the house only seemed to shrink, squeezing Teresa.

“Is there…a grandfather?” Beverly had asked, flipping through a small file on her desk, glancing at Teresa over her glasses, her eyes tired but kind behind red frames.

“No,” was all Teresa had said. There had never been a grandfather, just a boy who hadn’t been ready to be a father. Her parents were gone too, the rest of her family in Mexico. It was only and had ever been her.

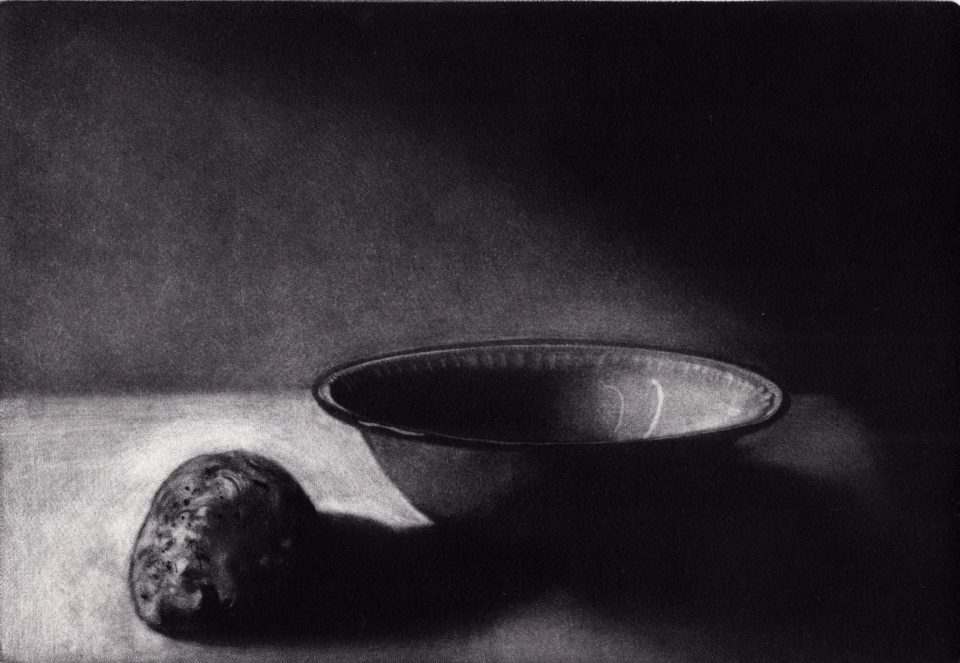

Now Teresa paced, needing something to do. Finally, she went to the kitchen. Food, of course. Food would wake the girl. Thick slices of white bread dipped in egg, then dusted with crushed corn flakes, browned in a pan with butter. Bacon, fried.

Mariam stood at the threshold of the kitchen wearing too small Christmas-themed pajamas from the bag of clothes the church had gathered for her.

“Wash your hands and we’ll eat,” Teresa said.

Mariam ignored her and sat at the table, eyes dazed with sleep. Teresa set two plates down, then the plates of French toast and bacon. Mariam reared back.

“Ay, sorry,” Teresa tsked.

She pulled the plate of bacon away but still the girl glared at it. Teresa brought it to the stove. Mariam refused the syrup Teresa proffered and picked up the toast with her hand. She took a tentative bite. Surprise passed over her face. She blinked rapidly, taking in the space around her, including Teresa, with hooded eyes. She bit and chewed with restrained delight, hungry but dignified.

“Have more,” Teresa insisted.

Mariam shook her head, looking at the plate of toast.

“I’m tired,” she said.

“Okay.”

Teresa went back to the stove to refresh her coffee. When she turned back, Mariam was gone, a slice of toast missing from the plate. Caridad’s daughter, indeed. Teresa bagged up all the pork in her fridge to drop off at the church community kitchen.

Mariam resurfaced in the evening, hovering at the threshold of the living room while Teresa sat on the sofa with a bundle of emerald green yarn in her lap. She patted the space next to her. Wheel of Fortune played on low volume on the television.

“I’m not very good.” Teresa held up the panel she’d knitted. “This is supposed to be a sweater but will probably end up being a scarf. I have a lot of scarves,” she sighed.

Mariam looked over at the bundle like it smelled bad. She clasped her hands between her

thighs.

Tomorrow was Sunday, church. Mariam would have to go with her. Teresa was apologetic.

“After service, we can have lunch and go shopping,” she offered.

Mariam shrugged. Teresa opened then closed her mouth. “Don’t push,” Beverly had advised. “Wait till she’s ready.”

“How will I know?” Teresa had asked.

“You won’t,” Beverly hedged. “You’ll make mistakes. This is an act of faith, Ms.

Benicio. You’re going to have to trust the process.”

Faith. Trust. The words like firm hands pressing one shoulder then the other against a

wall.

The women at church found nothing to redeem Mariam.

“She’s…very black,” Nina whispered to Teresa while she waited for Mariam to come out of the restroom.

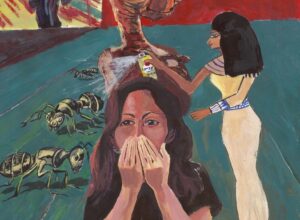

Heat bloomed behind Teresa’s eyes. She understood for the first time the meaning of the word fury. It stopped her tongue; her mouth an inferno. Caridad’s words all those years ago. “Anti-Black bullshit, mami.”

Teresa had always disagreed. They were darker than everyone else, but still brown. Their hair was more tight curl than loose wave, but it didn’t matter. She’d insisted it hadn’t mattered, even as she sat at the salon for hours getting her hair straightened, even as the tias pestered her to stay out of the sun and wear muted colors to dull the deep copper of her skin, and as the men smiled lasciviously and called her negrita. And now her church family, the only family she had, speaking it so plainly. She pictured Caridad smirking knowingly at her, shaking her head like she was the naive girl and not the mother. Teresa left the church without a word. The women did not call her back.

Teresa plunked a box of corn flakes into her shopping cart. She looked up to see a Black woman a few feet away scanning the ingredients on a box of granola. Her hair was thick and shiny, parted down the middle with two french braids that met at her nape and coiled into a neat bun. Teresa walked over to her.

“Excuse me,” she said. “Your hair, it’s very pretty.”

“Oh.” The woman patted her hair. “Thanks.”

“My granddaughter,” Teresa continued. “She is—” Teresa knew not to say negro. “She is Black.”

The woman raised her eyebrows. “Ah. And you need help doing her hair,” she finished.

“Yes.”

The woman chuckled and pulled a phone out of the back pocket of her jeans and scrolled through it with her thumb. Teresa walked out of the store with a slip of paper in her jacket pocket, an address with a date and time written on it.

Mariam had a new bounce to her step when she and Teresa left the salon. The stylist had washed and deep conditioned it, oiling and fashioning it into two strand twists, pinned back behind Mariam’s ears and trailing down to her shoulders. “Do you have a silk scarf?” the stylist had asked. “She’ll need a silk or satin scarf or bonnet,” she’d told Teresa, “to protect her hair and keep it moisturized.”

At the car, Teresa placed a glossy plastic bag with styling products on the floor of the backseat. Mariam stood on the sidewalk looking out across the street. She gestured towards a mustard-colored building with a mural painted along one wall.

“What’s that?” she asked.

Teresa squinted at the sign. “That’s a library. It looks like it’s open. Do you want to go

in?”

Mariam nodded and walked across to the front door. Teresa followed. A low hum of activity greeted them as the doors shushed shut behind them. They walked in timid steps towards the front desk. The librarian was a young man with long black hair tied back in a ponytail. He led them to the young readers section and tapped his palms on his thighs as he scanned the shelves.

“Ah, here’s a good one,” he said.

He pulled a hardback book from the shelf and handed it to Mariam. Teresa peered over the girl’s shoulder. Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. The girl on the cover was dark brown like Mariam, her arms folded and a determined look on her face, standing amid a field of flowers, clouds of smoke billowing up behind her. Teresa knew the choice was no accident. She smiled at the librarian.

More books landed in Mariam’s hands. A Wrinkle in Time, Bud, Not Buddy, and One Crazy Summer.

“That should be enough to get you started,” the librarian said. He leaned in and looked over his shoulders. “I’m not supposed to say this, but it’s okay to stop if you don’t feel like you’re connecting with the story. A good book is all about the timing.”

The corners of Mariam’s lips turned up in the first smile Teresa had seen. They left with a new canvas tote bag full of books and a library card that Mariam clutched in her palm.

Mariam liked reading. Soon she knew the route to the library and began to go by herself after school, coming home with more books. “Why don’t you read to me?” Teresa asked one time when Mariam sat at the kitchen table while Teresa cooked dinner. Mariam’s quiet, steady voice became a soundtrack of their evenings.

One night, reading Bridge to Terabithia while Teresa mended a tear in her work slacks, Mariam stopped and looked up from her book. She had gotten to the part where the main character, Jess, learns his best friend Leslie has died while he was away on a trip.

“She was lonely,” Mariam said.

Teresa stopped, her hand midair, fingers pinching the sewing needle.

“My dad left,” Mariam continued. “She stopped going to the mosque. Stopped praying. Said she was too tired. She started talking about how she was lost. I didn’t understand. She like, talked to herself. She was sad all the time, and nervous. She said she was gonna go back to the mosque. Then she said we were gonna go someplace else, start over. She said we could go anywhere. She promised me she’d get better. Then…”

Teresa felt pain in her jaw. She’d been clenching her teeth. She tried to swallow but it hurt. She shook her head, not knowing what to say.

“I never understood her,” Teresa said. “I didn’t try hard enough. Your mother, she was too big for this small world she’d been born into. She needed more than I could give her, more than this town could give her.” She shook her head again. “She tried though. She didn’t fail, Mariam. She kept trying.”

Mariam looked down at the discarded book in her lap, her face wide open and devastated.

“Is that it though?” she asked. “You just keep trying?”

Teresa sighed, thinking how her daughter, through all her one-sided arguments, had been trying to ask her that same question. Isn’t there more?

“Sometimes,” she responded.

Later that night, Teresa shuffled into her room and looked at the cross above her bed. She lifted her hand to her forehead to make the sign of the cross but stopped, unsure why she continued to do it or if she believed in its purpose. She dropped her hand. She didn’t know what she truly believed, but she knew she’d been given a second chance with Mariam, a chance to do more, be more. She’d been right, those years ago when Caridad accused her of not doing anything with her life. She’d had responsibilities, a child to raise, on her own with little help. But her daughter had been right too. She could have made time for her, time beyond work and school and church, time to have fun and enjoy life.

*

“Would you like to go to the beach?” Teresa asked Mariam one evening, months later.

They sat in wicker chairs on the porch, the sun heavy and low behind the trees, throwing an orange glow over everything. It was late May and already hot. The pine and bergamot that bloomed wild in the yard brought a cooling scent. Mariam bent forward towards the porch floor, trying to get a ladybug to crawl onto a leaf she held.

“There are beaches here?” she asked, sitting up.

“Yes,” Teresa laughed. “Not like in California, but yes.” She spoke like she knew, like she’d been to one, though she hadn’t.

Mariam held the leaf up to her eye level, watching the bug crawl across. She shrugged. The gesture had lightened over the months they’d been together. Less sulky and more nonchalant.

“Sure,” she said.

It was a four hour drive to Lions Beach in Elephant Butte, the longest Teresa had ever driven. Her hands shook terribly for the first hour, her fingers tight around the steering wheel. Gradually they loosened and stilled as she moved her eyes beyond the road in front of her and took in the flat, shrubby land around them, the mesas with their striated colors standing tall in the distance, their solid, constant presence calming her fears. They had been there before her and would be there long after she was gone. She could keep going.

Lions Beach was actually a reservoir. There were no chatty teens in bikinis and surfers chasing waves. The people they saw wore hiking boots and carried backpacks. The surrounding area was dotted with campsites. RV’s and pickup trucks dominated the parking lots. The water was a dazzling blue but still, not even the faintest ripple of a wave broke the surface.

“Well,” Teresa said after they’d settled their things down in the sand near the shoreline. “Do you want to get in the water?”

Mariam stood in long swim shorts and a shirt. At the Walmart back in Gallup, she wouldn’t consider any of the girls’ swimsuit options. A surprisingly chipper clerk had directed them towards the boys section where amid the camouflage and garish colors they finally found an acceptable outfit in a turquoise color with orange stripes.

“I…don’t know how to swim,” Mariam said.

Teresa had wondered if Mariam had been to a beach before, but was afraid to ask her and risk upsetting her. She’d started seeing a therapist once a week for the past two months, but she didn’t talk to Teresa about the sessions. She didn’t talk at all after them, her face clouded with sadness.

“I was hoping you would make me brave,” Teresa said. She held out her hand. “Come on, we’ll go in together.”

They stayed until close to sundown, eating tuna fish sandwiches and slices of watermelon from the cooler Teresa had packed. Back at the hotel, they shivered in the too-cold room.

“Go shower so you can warm up,” Teresa suggested as she fiddled with the knobs of the air conditioning unit.

Teresa went after Mariam and when she came out, the lights were dimmed but Mariam was not in her bed. She sat on the floor on her haunches, her hair covered in a black scarf. She turned to look at Teresa and for a moment she was Caridad all those years ago before she walked out of Teresa’s life. Despite the warmth of the shower Teresa shivered.

“I was just praying,” Mariam said.

Teresa blinked, aware of how her face must look.

“Oh yes, of course. That’s good.”

Teresa laid in her bed wondering when was the last time she’d gotten on her knees to pray. She felt God or the angels hovering, waiting for an answer.

Mariam spoke into the dark, her voice heavy with sleep. “Thank you, abuela.” The angels had blessed her with a kiss.

“You’re welcome, mija. Good night.”

*

It became a yearly plan. After that first trip to Lions Beach, Teresa planned longer ones, farther away. She brought home a map of the state, then bigger ones that showed the surrounding states, studying the veins of red lines that spread out in every direction. They visited Tucson, Denver and Salt Lake City, and finally, last year, a two-day drive to Pensacola. Teresa had spent so many years afraid to step outside of what she knew, now she embraced the unknown of the open road.

Then the time came for Mariam to leave. She rolled her suitcase to the front door next to her duffle bag and several large shopping bags. In her University of New Mexico sweatshirt and jeans, her hair in long pencil-thin braids that trailed down her back, she already looked like a college student. Teresa sat on the sofa, rubbing her palms together, wishing she had something to keep her hands busy.

“I could have driven you to Albuquerque,” she said.

“It makes more sense to ride with Salma and Khadra though,” Mariam said, her voice high and nervous.

She was carpooling to the university with her two friends, Muslim girls she’d met in high

school.

Teresa got up and walked over to the door. “Do you have everything? All your toiletries?

Your desk lamp?”

They both looked up at the sound of tires crunching up the driveway. Mariam ran over to the door and pulled back the curtain over the window.

“That’s them,” she called.

The girls giggled as they helped Mariam pack her things in the trunk. The wind picked up and almost blew Salma’s white scarf off her head, causing her to screech. Mariam walked back over to the porch where Teresa stood watching.

They faced each other. In the six years they’d spent together, the stiffness between them had loosened but never fully left. Mariam stepped forward in a rush and embraced Teresa, then turned away before Teresa could open her mouth. It was for the best. She didn’t trust her voice to speak.

Back inside the house, she sat at the edge of the sofa and rocked. She pressed her cold fingertips to her burning cheeks. She will be back. She will return. Faith. Trust. The hands on her shoulders were gentle this time.

She woke suddenly in the middle of the night. The returned quiet of solitude pulsed around her. She got up and walked across the hall into Mariam’s room. The walls were bare, the shelves emptied of her books. The sliding door to the closet gaped open, hangers slipped clean of their clothes. She ran a palm over the top of the chest of drawers and smoothed the quilt over the bed. The nightstand drawer was slightly ajar. She slid it open and found a tattered paperback book, a light blue cover with darker blue flowers scattered across, The Holy Qur’an written in white lettering.

She opened it. Her daughter’s names – the one Teresa gave her and the one she chose for herself – written side by side on the inside of the front cover. Her heart quickened. Caridad, returned.

She flipped through the yellowed pages of the book with her thumb. A torn flap of an envelope marked a chapter titled Mariam. It was the story of Mary receiving the news that she would be a mother, a story of her fear and acceptance. Teresa smiled as she blinked back tears, imagining Caridad discovering she too was going to be a mother, turning to the story of Our Lady for solace. Teresa hoped her daughter had been happier than she herself had been, finding out she was pregnant at eighteen. She hoped Caridad had felt a little less alone than she had.

A verse was underlined with a star next to it. It will be so. Your Lord says, ‘It is easy for Me, for I created you when you were nothing before.’ A door inside Teresa’s heart swung open, letting in a rush of cool, clean air. A moment she hadn’t known she’d been waiting for had arrived.