I had the opportunity to interview the award-winning poet Sara Elkamel. Her poetry draws deeply from personal and collective histories, capturing the delicate balance between loss, beauty, and our need for resilience. Her poetic process involves a deep relationship with language, merging with personal and cultural experiences that shape her writing. In a previous interview, Elkamel reflected on how images of violence and beauty intersect in her poems and how memory and serendipity play significant roles in her creative process.

“I think I work with images to play with juxtaposition, putting violence or pain side by side with beauty and possibility.”

Sara writes in English while being deeply connected to her heritage, expressing cultural specificity without over-explaining or compromising authenticity. Her inspiration, sound, and the tension between universality and specificity in poetry reveal a poet who is both intuitive and intentional. Her work often juxtaposes themes of confinement with symbols of escape, like birds, reflecting a longing for freedom and healing.

Let’s start by discussing Another Room to Live In, which was launched last March by Litmus Press, which is described as “an archive of encounters: a multilingual conversation between fifteen poet-translators, connected through friendship, correspondence, and cross-diasporic gatherings.” Tell us about how you came to participate and be included in this anthology?

Over the past 20 years, Tamaas has hosted an annual week-long poetry translation seminar, encouraging cross-cultural poet-to-poet translation across multiple languages, including French, English, Arabic, Dutch, Japanese and many more. This iteration of the project was focused on Arab writers, and the idea is that as a poet, you’re paired with a poet who writes in another language. For example, if I write in English and someone else writes in Arabic, I translate their work from Arabic to English, and they translate vice versa.

In my year, because of COVID, we did it online. I remember it was summer. I really wanted to work with this poet Rana al-Tonsi, who is an Egyptian poet, writing in Arabic. Sadly, she had just lost her mom before the seminar, and her grief meant she wasn’t in a space to participate.

Sarah Riggs generously invited me to participate, and paired me instead with Aya Nabih, who is also an amazing Egyptian poet writing in Arabic. I hadn’t been familiar with her work, so I was kind of anxious about working with someone I didn’t know, but I was really grateful that I was paired with her.

Because we were both in Cairo, we would meet almost every day during the week-long seminar at my home, we would translate each other’s work independently, in separate rooms, then show them to each other and discuss alternative choices.

Then we would come together with the other pairs on Zoom at the end of the day, and share our reflections as a group. So there was Mona Karim and Safaa Fathy, for example, Safaa was in Paris and Mona was in the States, as far as I remember, so they were meeting on Zoom. There were people all working together across the world, basically. I personally liked having that hybrid format, where I was working with someone in real life, but also then coming to this virtual collective space which felt, echoing the title of the anthology, like a room we would all go into together at a time when there was no other way to come together.

What was the format of your Zoom sessions? Did you primarily discuss how the translation process was going and any challenges that came up, or was it more like a workshop on translation?

The Zoom sessions were, above all, conversations. They were fluid, organic exchanges where we unraveled the nuances of translation together. I remember one discussion that focused on something seemingly simple yet surprisingly intricate: how to handle epigraphs. In English poetry, it’s common to see phrases like “for…” or “after…” to signal attribution or inspiration. But when we tried to find the equivalent in Arabic, we got caught between words like إلى (to) and من (from). How do we carry that same subtle intent across languages?

Sometimes, the questions we tackled were very specific and idiosyncratic. Other times, they blossomed into broader reflections on what it meant to encounter your own work in a different language — and how that changed your relationship with it.

In this space, there was a spirit of collaboration and a shared sense of experimentation. Even though some of the writers and translators in the group were already well-established, we were all on equal footing here, collectively puzzling through questions of craft and practice.

The Tamaas Translation Seminar describes the act of translation as a poetic communion — a way to challenge foundational narratives and “live” in multiple languages. How has participating in this multilingual exchange influenced your writing and your relationship with language? Do you see translation as an extension of your poetic process or as a distinct creative practice?

This was the first time my work had been translated into Arabic, and the experience was transformative. When Aya would ask me, “Did you mean this… or that?” I often realized I meant something else entirely — a third, unexpected meaning. This process opened up new possibilities, and reshaped, for instance, how I approached the endings of my poems.

One moment that particularly struck me was when Mona Kareem remarked that my work “felt so right in Arabic, as if it was intended to be written in Arabic.” That was incredibly affirming, and made me reflect on the fluidity and adaptability of language.

The seminar included participants who were also French speakers. Were the sessions primarily conducted in English, or was there a mix of languages?

While the sessions were mostly conducted in English, there was a natural flow between languages. Sometimes, when something was said in French, Sarah would translate it into English for the group, for example. We were eager to support each other and find ways to bridge any gaps.

How did the dynamics of the seminar evolve in this multilingual setting?

While I only attended the virtual sessions, I saw photos from the in-person meetings of previous years, which made me curious about how those dynamics unfolded. Even online, the sense of community and linguistic exchange was palpable. It felt like we were all navigating language together, expanding our understanding of both translation and poetry.

Not every Tamaas seminar results in an anthology. Can you talk about the unique nature of this one?

Actually, Another Room to Live In is a composite anthology, bringing together work from various iterations of the Tamaas Translation Seminar. Not everyone featured in the collection participated in the same annual gathering. Some poets were part of the Paris seminars, for instance.

The idea for the anthology emerged organically after the seminars, I believe. Initially, the goal wasn’t to produce a collection but primarily to nurture a collaborative practice— to create this open, liminal space of possibilities where poets and translators could engage deeply with language and each other.

Over the years, the results of these annual workshops were published in READ: A Journal of Inter-Translation, but the concept of a full anthology didn’t solidify until everything aligned: the body of work, the vision, and an interested publisher (Litmus Press).

I think that probably, at some point, Sarah and Omar recognized the incredible work that had been generated and saw the potential for a collection. The result is this anthology, a testament to the creativity, collaboration, and fluidity that the Tamaas seminars inspire.

In the anthology Another Room to Live In, your translations are paired with translator’s notes and author notes. How do these reflective writings influence your experience as a translator and what do they add to the work itself?

The translator’s note is something I’ve often been asked to write to accompany my translations. It’s a way for editors to contextualize—or even justify—why a particular work is being presented and how it journeyed from one language to another. But over time, I’ve come to see these notes as a kind of personal check-in. They allow me to archive my choices, to reflect on who I was at that specific moment, and to understand why I made certain decisions. It’s such a gift to be able to do this, especially since so much of the translation process—drafts, musings, struggles—often goes unseen. In the end, all anyone typically sees is the polished poem, while the process itself is silenced.

Even though I often dread writing translator’s notes, I appreciate having them as a record. They’re a tangible archive of my journey through the translation.

What I found particularly exciting about the anthology was the invitation to write author notes as well. I’ve always bristled at the question, “What do you write about?” because poetry, to me, isn’t really “about” something—it’s about the poem itself. But crafting an author note was a challenge I welcomed. It forced me to articulate, dialectically, what I’m trying to achieve in my work.

And what I love most is seeing the translator’s note and the author note side by side in the anthology. These two perspectives provide a dual vision of the same work, which enriches the reading experience. It’s a rare and beautiful way to witness both the creation and the re-creation of a poem.

How did your collaboration with Mona Kareem come about, and what role did the Tamaas Translation Seminar play in connecting you both?

Tamaas gave me the incredible opportunity to meet Mona Kareem and build a very special relationship with her. We first encountered each other during the 2021 seminar. During the seminar, our interactions were mostly in group settings, like those lively, communal dinner-table conversations. We didn’t get the chance for a one-on-one discussion right away, so we continued our conversation through email afterward.

Mona had seen some of my translations of Aya’s work, and I had admired her poetry in Safaa’s translation and the original Arabic. That mutual appreciation sparked the idea of collaborating.

A few months later, I was in New York for my final MFA semester at NYU, and Mona was passing through the city. We met at Café Greco, this wonderfully eccentric, old café near NYU in Manhattan. Over tea and coffee, we had a rich conversation about her work and the themes we share.

Before parting, I asked her to send me her books so I could explore translating them. When the books arrived, I tucked them into my suitcase alongside the other poetry collections I was bringing back to Cairo. My suitcases are always full of books. After finishing my MFA, when I no longer had the structured routine of writing a poem each week, I felt excited to try something new. Translating Mona’s work was a natural next step.

I distinctly remember a trip to Luxor and Aswan in early 2022 — sitting on the train, immersed in one of Mona’s books, translating as I travelled. That’s how the relationship started and it was that moment which marked the true beginning of our collaboration.

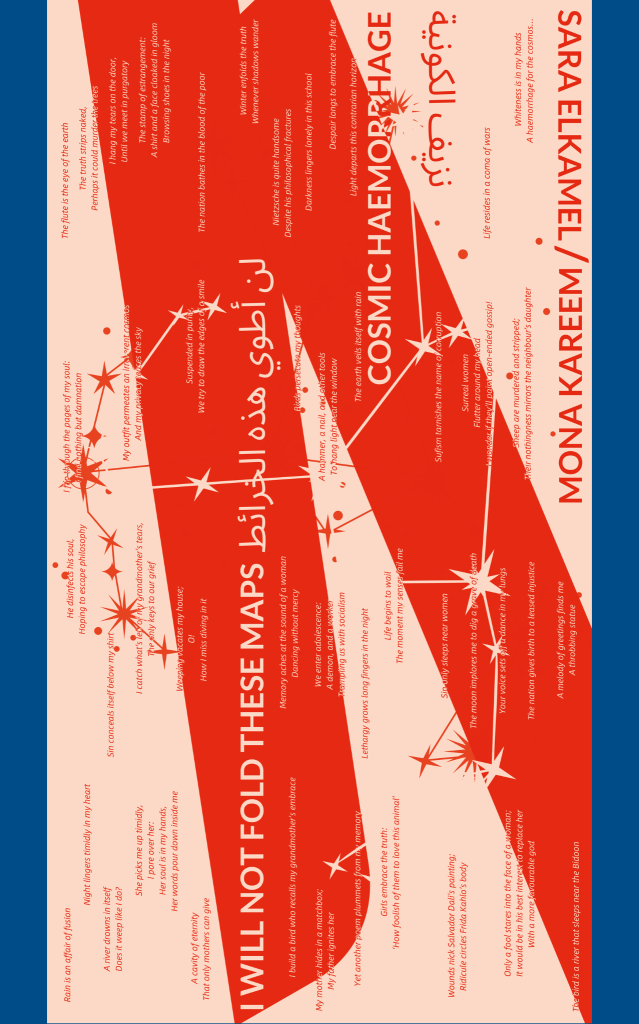

Your critically acclaimed translation of Mona Kareem’s I Will Not Fold These Maps stands out not just for its exploration of exile, grief, and resistance, but also for how it challenges traditional translation practices. Can you tell us about your approach to this translation?

Our translation process is deeply collaborative. I’d translate a section and share it on a Google Doc, and then Mona would dive in, leaving comments and suggestions. We’d have these rich discussions in the margins, talking through intentions and exploring possible solutions to any challenges that came up.

What made this process particularly rewarding was Mona’s flexibility. Much of the work I translated was written when she was 14 — over two decades ago. That distance gave her (and me) a certain freedom; she wasn’t overly attached to the original text. This openness allowed me the space to make creative decisions and occasionally shift the direction of the translation.

This was a very different experience from working with Aya, who has a more fidelity-driven approach to translation. Aya’s focus on staying as close as possible to the original text taught me a lot and made me appreciate that precision. But I found that the more fluid and open approach I had with Mona aligned better with my own poetic sensibilities.

To me, a text isn’t static. Even if you obsess over every word, comma, and nuance, time itself can reshape a metaphor or alter the resonance of an image. I embrace the idea that translation is one of those forces that can transform a text — not necessarily “change” it; it’s an approximation of everything that falls under the realm of change. Sometimes, it feels expansive, like opening the door to new possibilities; other times, it’s about narrowing the focus.

This collaborative, dynamic exchange reflects what I love most about translation: it’s a living, evolving process, just like poetry itself.

So your collaboration with Mona Kareem is still ongoing, even after I Will Not Fold These Maps, right?

Yes, absolutely! We’ve completed a full-length book together, which we’re now submitting to publishers. My work with Mona has been incredibly rewarding. Editors have been so receptive, and everything of hers that I’ve translated so far has found a home in literary journal or magazine.

I Will Not Fold These Maps was commissioned by the Poetry Translation Centre in the UK, and they produce these really beautiful chapbooks. I actually have a few on hand right now because the Cairo Art Book Fair is coming up, and I’ll be selling some of their books. They’ve published works by poets like Najwan Darwish and Habib Tengour—each chapbook is a gem. Mine even came with a set of postcards, which added such a lovely touch. These books are stunning, yet so many people remain unaware of the work the Poetry Translation Centre commissions and publishes.

The project came about when the Poetry Translation Centre approached Mona, and she brought me on board. It was an amazing experience, especially because we got to collaborate with Nashwa Nasreldin, who was the editor on the project. Nashwa, now a dear friend, is also a poet and translator. It felt like an extension of the Tamaas experience—this time with Nashwa and I working on the poems as translator and editor, while Mona stepped back from the process.

I really enjoyed that dynamic. We were able to engage with the poems purely as poems, focusing on how they stood in English rather than their proximity to the original Arabic. Sometimes, in translation, you need to step away from the source and just work with what’s in front of you in the new language.

Nashwa was incredible—so sharp, insightful, and precise. It was a humbling experience, too. As a poet, I often feel I let my ego share the room with me. There’s a point where I decide, “This is the choice,” because otherwise, I’d obsess forever. But Nashwa challenged me, and I loved the moments when I realized I might have been wrong, that there was a better choice to be made. That kind of pushback made the work richer and more nuanced.

Sometimes, a good editor really challenges you—but that also requires being receptive. And we all know how writers and poets can sometimes be like, “If you change another word, I’m pulling the whole piece!”

Oh, I definitely have some of that instinct. I get really attached to my choices, especially in translation. But many of the poets and editors I work with are generous enough to say, “You have the final say.” And I appreciate that. I do believe the poet or writer should have the last word—whatever feels truest to their voice or their translation. But yes, there’s always that tension between staying true to your vision and refining the work. It’s a delicate balance.

After I Will Not Fold These Maps, have you started working on other translations, aside from the full-length book you and Mona are developing?

Yes! Mona Kareem has published four poetry collections in Arabic, and our new project includes a selection from each. We brought Nashwa Nasreldin on as a consulting editor again because we loved working with her. She provided invaluable input on the selection, structure, and overall shape of the book—sometimes, you need someone to give you a bird’s-eye view.

In the meantime, I’ve continued translating other poets. After the Tamaas seminar, I did more work with Aya Nabih. I also finally got to work with Rana ElTonsi who as I mentioned before, I’d initially wanted to collaborate with during Tamaas, but it didn’t happen then. We met, talked, and I translated some of her poems, which was really exciting.

Is Rana based in Cairo as well? And do you use the same process with her that you did with Aya—meeting in person first, getting to know her, and then translating?

Not exactly. With Rana, we met socially a few times, just talking about life, love, and writing. Then, I worked on the translations independently, putting them into a Google Doc. She’d add comments if needed. It was a more relaxed, informal process.

And you mentioned working with Farah Barqawi, a Palestinian poet who lived in Cairo but later moved to New York. How did that collaboration unfold?

Farah Barqawi, and I became close when she moved to New York for her MFA in nonfiction. One time, we were asked to do a bilingual reading together. She read her poem in Arabic, and I presented the English translation. It was fascinating—when she read it in Arabic, the audience laughed; it came across as light-hearted. But when I read my translation, it felt somber and serious. That experience really highlighted how tone and reception can shift between languages. That event also really imprinted in me how important it is to have that space where we could read something bilingually and have a diaspora audience understand both resonances.

It sounds like that experience went beyond just poetry—it became about community, connection, and shared understanding. Did you continue working with Farah after that?

Yes, after that, I continued translating some of Farah’s poems. When the war in Gaza started, her mother—who still lives there—began sending daily dispatches to Farah. Farah edits them and shares them with a small group of us translators. We organically formed this collective to help bring these dispatches into English. It’s a very different experience from translating poetry.

That’s really powerful. I love how these daily translations are intimate, personal, and entirely collaborative. It’s not just about the text; it’s a shared experience between a mother, a daughter, and a group of translators. It reminds me of something Mejdulene Bernard Shomali touches on in her monograph Between Banat: Queer Arab Critique and Transnational Arab Archives. She writes about how certain works bypass mainstream institutions and instead travel by word of mouth, reaching people in private, intimate ways. These works perform political and social labour within their communities, offering a record of lived experiences and articulating differences from within.

It feels like what you’re describing—the way these dispatches circulate and connect people—is exactly what Shomali talks about: a form of distribution that resists commercialization and exists outside capitalist frameworks. It’s relational, dynamic, and deeply meaningful.

Yes, exactly! It’s about care, love, and support—not just writing and translating, but the connections that form around those acts. This process has its own rhythm, its own dynamics and distribution. It exists in a separate sphere, one that’s profoundly intimate and deeply rooted in community.

You mentioned that after wrapping up the draft of Mona’s book, you felt a bit like an “empty nester.” What other new collaborations filled that space for you?

Most recently, I’ve started working with Dalia Taha, a Palestinian poet and educator based in Ramallah. This collaboration is fresh—only two or three weeks old. I’d been following her work for years, ever since I read a poem of hers in Makhzin, the bilingual journal launched by Mirene Arsanios and Ghalya Saadawi in Beirut in 2014. After finishing the draft of Mona’s book, I felt a bit like an empty nester, so I reached out to Dalia to see if she had anything I could translate.

We use Google Docs, but Dalia also prefers to meet on Zoom. We spent two hours discussing minute details about word choices. Each poet has different priorities. For Dalia, tone is everything—she wants the tone to carry across seamlessly into the translation. Her current work grapples with the war and its harsh realities, and it’s not trying to be beautiful. The space for beauty is limited, probably because it’s engaging with so much ugliness.

Your collaborations flow from one woman to the next—from Aya to Mona, to Farah, and now Dalia. These choices are intentional because you clearly love their work, but do you think it’s just a coincidence that they’re all women poets? Or do you find yourself drawn specifically to translating women?

It’s always such a joy to collaborate with women poets, but I don’t think it’s a conscious choice. I just find myself naturally drawn to the voice of a woman speaker in a poem and to the poetics that emerge from a woman’s experience. There’s something distinct about that perspective and the way it resonates with me.

It seems like this process is almost subconscious. These connections arise organically—from relationships, from reading, and from the urge to reach out. You’re following your gut, and it leads you to the poets you’re drawn to, whether they’re women or men.

But I also realize we haven’t talked much about your own poetry. Translating is a significant commitment, and not every poet makes that choice. Has your work as a translator ever felt like it suppresses or sidelines your own writing, or have you managed to balance both?

I’ve managed to do both, but I find translation easier to dive into. With translation, the conditions don’t have to be perfect. I can just start working. But for my own poetry, I feel like I need so much more. I need language—not just words, but material to shape, like clay or dough. And sometimes, that clay feels completely out of reach.

Translation, on the other hand, provides something to work with right away. It’s like a respite because I’m not starting from scratch. With every poem I write, I pour everything I have into it, and then I feel emptied out, like I might never write another poem again. But with translation, I can just turn the page and have something new waiting for me. It makes me feel less anxious.

There’s still frustration, of course. Sometimes, I can’t quite access what I need in the translation. But because I focus on living poets who write in Arabic, I have the luxury of reaching out to them. If I get stuck, I can ask questions like, “What did you mean here?” or “Is this based on a memory?” I can ask those questions about my own poems too, but I don’t always have the answers ready.

Does your work as a translator ever spark ideas for your own poetry? Do you find yourself moving between the two, translating and then getting inspired to write something original?

No, not really. The translator’s hat and the poet’s hat are very separate for me. The only overlap that happens—and it always makes me chuckle—is when I come across a word or a piece of syntax in the translation that feels very much like my word or my syntax. Then I wonder if I’m holding back in the translation because I want to save that word for my own work. But I’m at peace with that little struggle.

That makes sense. It’s great that you’re so aware of these small internal struggles. It’s a way of staying connected to the creative process. Translation really is recreation—you’re still creating poetry, even if you’re not writing it from scratch.

Exactly. Translation is deeply creative work. You’re not starting with a blank page, but you’re still moulding the language, shaping it into something new. It’s definitely not easy.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to start translating poetry? Should they take a workshop, contact the poet directly, try translating on their own, or even pursue an MFA?

I’d suggest starting on your own first, just experimenting without any pressure to publish or share it with the poet. See if you enjoy the process and what it brings to you as a writer, reader, or person. Then, reach out to the poet and start a conversation about collaboration.

I can’t recommend the collaborative aspect enough. Don’t just send the translation for approval—really engage with the poet. That’s something I learned from the Tamaas experience and want to carry forward in my translation work. Think of it as sharing a room together, which brings us back full circle to Another Room to Live In.

Thank you so much for this wonderful conversation.

Sara Elkamel is a poet, journalist, and translator based in Cairo. She holds an MA in arts journalism from Columbia University and an MFA in poetry from New York University. Her poems have appeared in Poetry, Ploughshares, The Yale Review, Gulf Coast, The Iowa Review, among other publications. A Pushcart Prize winner, Elkamel was also awarded Southeast Review’s 2023 Gearhart Poetry Prize, the Michigan Quarterly Review’s 2022 Goldstein Poetry Prize, Tinderbox Poetry Journal’s2022 Brett Elizabeth Jenkins Poetry Prize, and Redivider’s 2021 Blurred Genre Contest. She is the author of the chapbook Field of No Justice (African Poetry Book Fund & Akashic Books, 2021).