In a moment when images once again shape global understandings of Palestine’s occupation, the genocide unfolding in Gaza since October 7th has exposed, with unrelenting brutality, how narratives of the Israeli settler-colonial state are sustained, circulated, and shielded from scrutiny. Long before today’s horrors, another battleground had already been drawn across the visual record: the archives, where photographs, captions, and catalogues propagated the ideological scaffolding of Zionist settlement and the ongoing occupation.

Matt Hanson’s review of Rotem Rozental’s Pre-State Photographic Archives and the Zionist Movement returns us to these origins, tracing how early photographic practices helped manufacture a visual grammar of entitlement—one that still shapes the world’s gaze. Her work arrives at a time when the politics of evidence, memory, and representation are no longer abstract questions but matters of life, erasure, and historical reckoning.

Among the hundreds of thousands of protesters who gathered in Israel’s streets from January to October 2023, the opposition against the ultraconservative judicial overhaul was not merely over the so-called Basic Laws of the nation’s unwritten constitution; it was also about upholding Israel’s national self-image.

The notion that Israel remains the region’s leading democracy is constantly challenged, defied, and threatened with unprecedented fervour. The ruling coalition of religious rightists is eroding the secular, pluralistic vision of the nation’s future by promoting a form of authoritarian Zionism, where Jewish identity is reduced to an ethnolinguistic caste intent on occupying Palestine and claiming territorial rights based on over a century of ideological settlement.

Almost immediately after its invention in 1822, photography was used to exoticize travelogues or as an instrument of colonial surveillance. Photography played a key role in exporting the Holy Land to the modern world through mechanical image production.

As a curator and photo-historian, now serving as Executive Director of the Los Angeles Center of Photography, Rotem Rozental demonstrates in her book, Pre-State Photographic Archives and the Zionist Movement, how extensively this visual material entered Israeli archives through the Zionist imperatives of the Jewish National Fund, helping fabricate “historical evidence” in what remains one of the most appalling land grabs in the postcolonial era.

Cover of Rotem Rozental’s Pre-State Photographic Archives and the Zionist Movement, Routledge, 2023

As a formidable contribution to Routledge’s History of Photography series, Rozental wrote a rigorous and dense academic title that is likely to remain relevant for scholars keen to unearth skeletons from Israel’s darkest closets, especially those constructed by the Jewish National Fund’s vast treasury of photography chronicling the rise of pre-state Zionism into a project of modern state formation.

Earnestly, if toothlessly, Rozental critiqued the self-fulfilling fabrications of Jewish nationalist futurism as conceived by the very preemptive photography archives that anticipated and later enshrined Israel’s statehood.

With light doses of historical theory reinforced by contemporaries like Ariella Aïsha Azoulay and by the modernist canon, such as Michel Foucault, Rozental frames the repetitive thematics and confrontational realities of nationalist aspirations. Between territory and diaspora, Hebrew and Yiddish, Arab and Jew, Ashkenazi and Sephardic, to name a few of the archetypes that appear among the diverse sociopolitical distinctions that were mostly constructed by European Jews through photos taken since the mid-19th century, Rozental examines the underlying dogma of Zionist settlement in the Levantine region, known by Jewish settlers as Eretz Israel.

Under the shadows of Ottoman Palestine and its British Mandate, professional and amateur photographers, not only Jews, furnished images which, since 1926, archivists at the Jewish National Fund have cherry-picked for publication, working systematically to disseminate image-based Zionist propaganda, providing a veneer of evidence and historical precedence to justify and promote their ideologically biased views of Israeli nationalism, history, and identity.

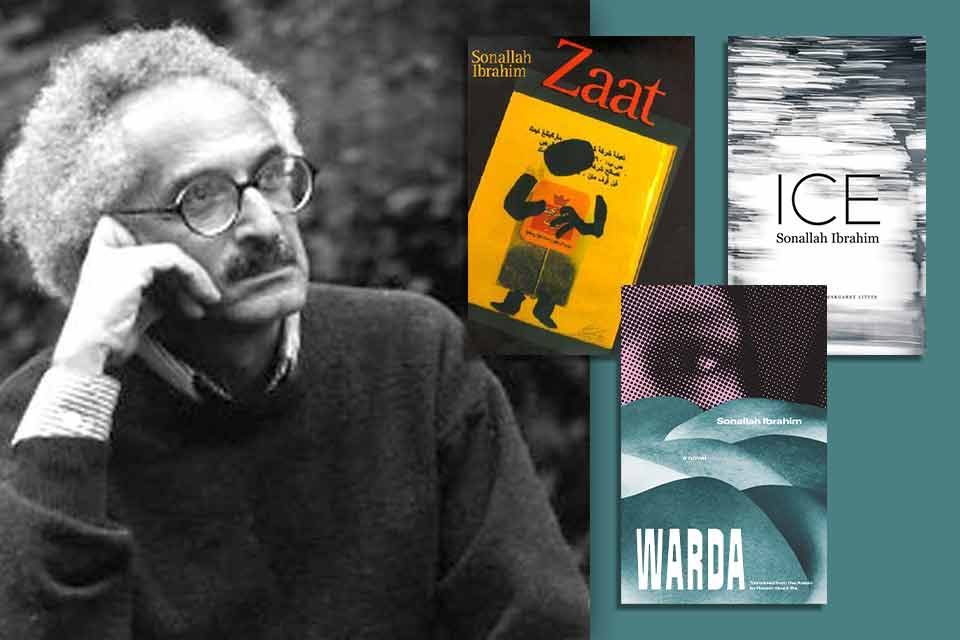

David Wolffsohn, Herzl Meets Kaiser Wilhelm II, 1898, photomontage

Rozental’s prose only lightly excavates the intellectual chorus of theoretical references threaded throughout her work, echoing Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari, Lacan, or Derrida, surnames synonymous with the requisite, if opaque, terms of endearment for the mimesis of cultural criticism.

Her passages of historical and ideological explanation are often redundant, justifying book-length work, only to circle back and re-emphasize them by extrapolating on the leitmotifs of nascent Zionist identity; pioneers of brazen territorial settlement who emerge from authoritarian rule under Germans, Russians, Ottomans and other imperialists in diasporic exile only to reinvent themselves as nation builders as the collective wunderkind of a supposed socialist democracy in the Middle East.

Her text, while distinct in its focus on photography’s visual historiography, nevertheless reiterated many themes that recur in the vast body of scholarship on subjects pertaining to the birth of modern Zionism, such as the portrayal of physical empowerment among diaspora Jewry transformed into a militarized, agrarian national workforce. Recent and forthcoming books on the topic vary widely in scope, but together number nearly a thousand titles. This is evident in her repeated points about the widespread distribution of photographic production across the Ottoman, French, and British imperial territories.

Rozental writes: “In the case of the [Ottoman] Sultan, much like it did for other colonial regimes during the nineteenth century, photography served as both an effective means of observation and an important tool of dissemination of an image of sovereignty across the Empire.” And then, later: “In the Second Empire of the mid-nineteenth century, photography was seen as a powerful tool for propaganda and public relations…”[1]

While advancing a robust interdisciplinary study of textual and visual sources, Roztental’s book ultimately fails to gain sufficient momentum to carry its curatorial inquiry into new horizons of critique. Again, in the first chapter, “In and Out of the East: Travelers, Believers and Contested Truths,” Rozental foregrounds photography’s entanglement with empire, citing:

“[Keri A.] Berg shows how photography’s early focus on the Orient served as an imperial agent for political motivations. Photography was regarded as “the official arbiter of the real,” asked to serve disciplines such as architecture and archeology as a “documentary tool,” recording and preserving the past by neutral mechanical means.

Rozental repeatedly affirms her critiques of Zionist authority as the main force behind co-opting the technological proxy of early photography. She emphasizes that, as a marker of 19th-century scientific progress, photography was widely regarded as an objective instrument for exploring nature—its perceived neutrality lending weight to the colonial narratives it was tasked with upholding—rather than as a medium of individual artistic expression, a point she explicitly makes.

For the Zionist-Orientalist, photography could depict Palestine as the biblical landscape of its ideological imagination, complete with Indigenous communities, fertile land, and strong pioneers. A notable dissent against this view briefly emerged among Yiddish revivalists as a borderless movement they called Diaspora Nationalism, which Rozental thoughtfully discusses as the promotion of a “stateless Jewish nation.” This movement offered an intellectual alternative to Zionism, an idea that later inspired the founding of YIVO[2], a U.S.-based early modern Jewish archive that preserves the work of an alternative sociopolitical movement which runs parallel to the Jewish National Fund (JNF).

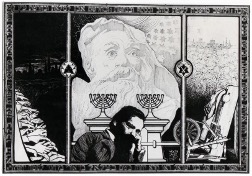

Unpacking the mutual conflation of Zionist photography and Orientalist representationalism, Rozental aptly excavates the origins of Bezalel, the school synonymous with Zionism’s modern, national art heritage. In its attempts to express a localized version of Jewish culture in Palestine, Bezalel extended its reach beyond the nascent realm of photography to a variety of fine arts and crafts to convey a distinctly Zionist, and later Israeli aesthetics. Among other prerogatives, its pioneers in the field of cultural production produced the soft power equivalent of the “muscle Jew,” a visual trope bearing frightening similarities to Nazi fascist iconography embraced by German-Jewish Zionists, a connection further explored by Rozental’s fellow Routledge author Todd Shmuel Presner in his 2007 book, Muscular Judaism: The Jewish Body and the Politics of Regeneration.[3]

Ya’acov Stark, Emblem of Bezalel, 1905–1907, postcard

Rozental also sampled historian Daniel Boyarin, whose work she paraphrased by writing that, “Zionism for Sigmund Freud provided an opportunity to expel the femininity and suppressed homosexuality of the Jewish body, so that it might reemerge, paradoxically, in the heroic image of the classical ideal.”[4] More directly, Rozental references the eugenics-sympathizing sociologist and photographer Arthur Ruppin, highlighting suggestions that his “conception of Jewish racial characteristics influenced the German antisemitic perception of Jews as a race.”

Pre-State Photographic Archives and the Zionist Movement concludes by emphasizing the institutional deadlock Rozental faced, a barrier that will continue to mire serious surveys of Israel’s photography archives in the classified files at the Jewish National Fund, much of which is currently sealed and unavailable to the public or researchers for the next fifty years.

While the photographic archives she has explored express a century and a half of multigenerational immovability over ideas that have been forcefully imposed in retrospect as revisionist history, simultaneously atavistic and futurist, her documented walkthroughs into the archives of the Jewish National Fund are ultimately far from newsworthy investigations. The images she examines reference narratives that reinforce Zionist dogma, in which Palestine was a barren land devoid of Arabs (a narrative her father told her about his birthplace in a Jezre’el Valley kibbutz), bearing painful similarities to the genocidal thought apparatus of British colonialism known as terra nullius, which violently displaced Aboriginal societies by perceiving their territories as empty, unpopulated and therefore claimable.

As a curation of JNF propaganda, Rozental’s book primarily describes the photographs she accessed with historical and aesthetic insight. They show Palestine as an empty terrain, open to the pogrom-afflicted Jewish diaspora youths, who sought new lives and bodies as agriculturalists fulfilling Zionist ideals of socialist labour. In these publicized propaganda images, their toned muscles gleam under the Mediterranean sun, projecting optimism about their shared future in a fertile and welcoming land.

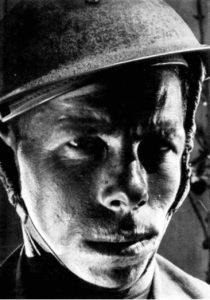

Helmar Lerski, from the series Jewish Soldiers, 1942–1943

Wilhelm von Gloeden, “Ahmend,” Picture Number 227, 1899

As historical actors marched on to create what became the State of Israel in 1948, photographs that testified to the Zionists’ long-provoked aggressions toward their expelled Arab neighbours and communities, and the religious ambitions of Western imperial powers, have largely remained unseen, out of public view. Yet, attentive readers of Rozental’s book will surmise that this does not mean such scenes were not documented by the many independent photographers who cultivated Israel’s archives.

For example, Rozental shares photos she took during a 2014 visit to the Palmach Historical Museum and Archive in Tel Aviv, including one that shows a woman in uniform, armed with a rifle, named Rina Fisch (Pearl), a paramedic at Nir Am. The image, sourced from the MOD—IDF & Defence Establishment Archives, depicts her youthful indifference as she gazes into the distance with a striking listless abandon. As Rozental interprets, “…moments of personal breakdowns and physical wounds emerge…”

Among its over 270 million photographs, accumulated since the late 19th century, those taken by Haganah soldiers are notable exceptions, as they turned the cameras on themselves, revealing their imperfect and complex humanity. About the archive, Rozental wrote that these images “undermine its coherence…as the photographed individuals embody the image the institutional archives aspired to conjure, they also undermine the characteristics of this typology.”

The JNF archive is organized by types that continue to shape and define the Zionist imaginary. However, these general categories are highly mutable, shifting with changes in popular and political perceptions of the past, present, and future, which influence how state-sanctioned history is organized and taught. Despite the picturesque promises of early ideologues and the JNF’s efforts to cement their legacy, the making of Israel’s national future, whether by past propagandists or today’s disapproving voices, remains as unwritten and speculative as Israel’s own constitution.

If Israel’s future remains unwritten, as Rozental suggests, then so too does the reckoning with the images that helped script its past—images that demand not only archival study but active ethical confrontation. Ultimately, we are reminded that archives do not merely preserve history; they manufacture it—and it is up to readers, scholars, and witnesses to name, resist, and overturn the erasures embedded in their frames.

[1] Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “A Photographer in Jerusalem, 1855: Auguste Salzmann and His Times,” October 18 (Autumn, 1981): 97-98.

[2] YIVO Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut (Yiddish Scientific Institute), founded in 1925 in Vilna (now Vilnius) and later relocated to New York, YIVO is a major research center preserving Yiddish language and culture. It represents a non-Zionist, diasporic intellectual tradition.

[3] Todd Presner, Muscular Judaism: The Jewish Body and the Politics of Regeneration (New York: Routledge, 2007).

[4] Daniel Boyarin, “Neshef HaMasekoht HaColonialiy: Tzionut, Migdare, Hikui,” [The Colonial Masquerade: Zionism, Gender, Imitation] Teoria VeBikoret [Theory and Criticism] 11 (Winter 1997): 123–144. [In Hebrew.]