My father once told me when I was young, that he could judge a man on three things: his hat, his shoes, and his walk. The first two, he said, were simple. If a gentleman walked in with a Stetson and a pair of gleaming spats, my father knew that on top of those he also wore a famous name; and that—like a fierce animal—he would need to be stroked gently and with friendly assurance eased into opening his green wallet.

But by his gait and walk, he said, the roaring tiger could expose a kitten, to be played with and teased.

Perhaps this was what went through his mind the day he sold the green Cadillac.

My father was a dancer, a puppet master—for with one false step or sleight of hand the wires of our lives could be twisted and the ankles of our souls irreversibly sprained.

He must have stood there, beneath the shade of the showroom door, calculating his equation. He would have performed the choreographed smile, analyzing the specimen that walked into the sun-dried lot and holding out his careful puppet master’s hand.

My father’s dance partner, as it were, waltzed over towards him, and the performance began. The man’s appearance was striking. His once elegant attire was disheveled and haphazard, and he grew a neglected mustache that drooped morosely over his grey lips. Over his hooked nose perched a pair of delicate spectacles that gave him the essence of one who is very, very old. In actual fact, it was almost impossible to determine his age—one could’ve placed him anywhere between forty-five and seventy-five years of age.

Over his thinning grey hair, he bore a squashed grey hat, which my father must have noted along with the large, scuffed leather shoes that shuffled along as he walked. He stood hunched, like a broken doll, and walked with slow, careful steps.

He fished a lighter out of his ancient jacket pocket and attempted to light a cigarette.

I say “attempted” because the offensive clicking was, of course, in vain. The uncomfortable moment soon ended as my father hurried irritably to give him a match.

The man murmured his thanks and hung the lit cigarette beneath his mustache.

They shuffled on between the shining hubcaps until they reached the green Cadillac, whereupon my father pulled the puppet strings taut and began his story.

I will never know what my father told this man; what he fabricated to suit what he thought to be the correct assessment of this man’s character.

I imagine he told stories of the fame of that green Cadillac and the good fortune that had brought him to it. A fairytale of some sort, where the Cadillac was the protagonist, the knight in shining green armor.

Whatever it was, the man seemed to buy it. He asked the price and my father told it without hesitation. The man coughed, and produced a green wad, which he peered at over his spectacles as he counted.

My father produced the key and with fake politeness, helped his client into the automobile. As the man drove out of the lot, my father must have grinned at his intelligence, his immense cunning. For that very same morning that green Cadillac had had a mileage of twenty thousand miles on the speedometer.

My father had sold scrap metal for five grand.

My father never was a good judge of character.

A week later, my father came home one night stinking drunk. Oliver and I used to stay away from him when he came home like this, but this time was different. He looked scared, really scared. He staggered into the house in drunken silence and grabbed my arm. The bourbon on his foul breath stung my eyes and I winced. Oliver started to cry.

“Pack your bags, Anna,” he said to me, “We’re leaving.”

I gathered our things quickly and hushed Oliver, holding him tight. The house looked empty, forgotten, as we glanced at it for the very last time.

We caught the night bus. The lights of the city played on the windows, rippling over the sleeping bodies. Oliver cried silently on my shoulder until he too fell into sleep. The night bus was quiet, the purr of the motor the only sound among the snores and silent dreams. The silver moon and the dancing stars watched over us all as we stole out of the city through the night, out of danger and out of sight.

A golden slice of dawn cut through the dozing slumber of the coach. It flooded the coach’s interior and poured over me, dousing me in early morning light. It spilled over the dry ochre grasslands of Maine soaking the dry fields in liquid light.

We rose over a rolling hill and the sun-soaked golden waves unfurled beyond the horizon. I gasped. With my breath, the bus seemed to come out of its spell, murmuring musically in between the offbeat rhythm of the struggling engine.

The night bus gathered a breath and dove into the waves.

“Get up,” Father grunted, gathering our bags, “We’re getting off.”

The bus sputtered to a steady halt and my father rewarded the driver. We were the only ones getting off. As soon as my sole grazed the baking tarmac, the night bus started off again and left us—Oliver, Father, and me—alone, in Maine.

We sheltered beneath the disappearing shade of the isolated bus stop while father clumsily wrestled with a yellowing map of the northern states. Not a breath of wind penetrated the deafening stillness of that moment. The bus stop seemed to be the only mark of human civilization for miles around. It was almost comical, that bus stop; the neatest, most perfect bus stop I’d ever seen, a little island amidst the wild golden grasses.

The sound of Father folding up the enormous map signaled that it was time to move on.

“It’s just a mile south of here,” he announced.

“What is?” I asked.

“Our home.”

“Do we have to walk?”

He snorted, “Unless you want to live at this bus stop.”

The heat of the unforgiving autumn sun scorched our backs all through the painful trek. I am glad to forget the unfortunate details of that first walk in the northern sun. What little memory I have of that scramble is probably best left to the imagination. What I will never forget, until my very last breath, is the setting sun over those familiar hills, the crunch of my weary boots on the dead grass, and the way my flame of hope was extinguished in those lonely first seconds when I saw the house I would spend the rest of my life in.

It was not really a home—and neither was it a house. It was more of a farm building, yes, a farm building—if farm buildings are built without consideration of live human inhabitants, that is. The wild rolling plains had left their mark on the grandeur of the building, that much was clear, and yet it still stood, triumphant, its two chimney pots intact, the only other structures near it a couple of small sheds and a derelict fence. Inside, it was surprisingly large, an expanse of grey, dead wood that would creak and whisper in the cold winter months.

Beneath my feet, it pulsated with a burning vital energy that seared my heart. It called to me, it implored me to come inside its terrible halls and I sensed it, I felt its evil before I could understand it.

I felt the need to scream, to run away from that house, that cold, frightening being, yet I stayed. I stayed when I could have run through that door, out into the arms of freedom; and so I imprisoned myself and swallowed back my screams.

Oliver ran with innocent delight around the building, marking it with the small piece of chalk he always kept in his pocket. He seemed so happy, so foolishly happy.

Father busied himself with opening shutters while I wandered over the grounds, my mind far, far away from this place.

Over the next week, we were alone. We met briefly in the middle of the day and gathered around the food Father had found in the village. It tasted like dust in my mouth. We wandered through the house, barely glancing at each other, drifting through it like ghosts. It was only on Saturday afternoon that we met Mr. Kips.

He came up over the hill, where Oliver spotted him, just a figure approaching the house. The figure became a man, a broad man with a bow-legged walk and the kindest face I’ve ever seen.

Father rose out of his chair on the front porch and stood there, unsure of what to do or say. That’s how we all felt as we watched him in those first unclear moments; a sort of amazement, our first interaction with human life in this seemingly deserted place.

“Mornin’,” he called out, “Beautiful day to be movin’ in, ain’t it?”

Silence.

“We heard y’all comin’ over the hill early,” his Maine drawl was clear as he stretched the word “hill” over two syllables. “Welcome to Cushing. I’m John Kips. Me and the missus live righ’ down there,” he gestured with his thumb down the hill. “An’ we were wonderin’ if you folks would like to join us over a pot roast tomorrow nigh’. The missus makes the best pot roast in these parts; at least I think so.”

He beamed up at us so that I could see the uneven gaps between his teeth. Shielding his face from the setting sun, he waited for an answer. The silence was deafening.

“I don—” Father began.

“We’d love to,” I interjected.

Defeated, Father looked at me then back at our new neighbor.

“Thanks,” he murmured quietly.

The man’s coarse face lit up. “Boy, the missus will sure be glad. Come ‘round any time ya like, we’ve always got somethin’ cookin’.”

“Thank you,” I nodded, sending him what I hoped was a friendly smile.

He winked at Oliver, then turned and went back the way he’d come.

I wanted to call out and beg him to take me with him, down that hill. Instead, I stood and stared after him, motionless, until he and the setting sun disappeared over the horizon.

That night was bitterly cold and seemed to shake all the warmth of the day out of the house. The relentless, howling winds passed right through the building, slamming open all the windows. I could feel the darkness slowly oozing in through every crack and fissure. In my mind’s eye, I could see the dry winds streaming over the dead grasses of the plain, tearing them apart like strips of paper. And I tried to feel the heat of Mr. Kips’s stove and saw the warmth spreading over the hill, wrapping itself around me, and bringing life back to this dead place.

We huddled together on the bare wooden floor and shivered in our wretchedness. The walls mocked our misery. My eyes were too weary for tears and my threadbare scarf was bound so tightly around me that I could not move my arms. And so I lay there, as still as the night was wild, until sleep finally pulled me out of my nightmare. And all I dreamt of was what lay at the bottom of the hill.

The next day passed swiftly, just as I wished it would, so that soon it was time for us to venture over the hill. For a day and a half, we had lived with our empty stomachs, but now the gnawing pain wracked our insides. Father’s supplies of food had run out as quickly as they’d come. We pushed on quickly down the hill, reduced to nothing but ravenous beasts.

We came to a thicket of trees.

What lay beyond those trees was a house. A quaint, white house that desperately desired the refreshing lick of a paintbrush. Further back, I could make out a couple of other buildings, but something inside me said that this was the one. Perhaps it was the friendly smoke that wafted out of the chimney, or maybe the muffled shouts and giggles of happy children that trickled to my ears that decided this.

She came to the door still chuckling at someone’s hilarious joke. “Oh, you’re a cheeky one, you!” she chortled. I was panting and smiling wildly into Mrs. Kips’s kind face when I realized that I’d run up those rickety old steps and left Oliver and Father trailing far behind me.

She was tall, wild, and wide-hipped, and when she smiled you could see the broad gap between her front teeth. She had long auburn curls that were woven into a messy braid over her shoulder. Her son sucked his thumb while he stared silently at me from her strong arms, held close to her large chest. “Why hello there,” she beamed. “Kids, they’re here!” she yelled into the house. The sound of scraping chairs could be heard as the family raced to the door.

“’We’d better get you a drink!” she laughed. I said nothing; all I wanted to do was stare up at her, hoping that she would smile at me again.

“Anna, don’t you go off like that again!” Father’s fierce voice made me start. “You could’ve been—why hello there, Mrs. Kips,” the change was sudden and now his smooth salesman’s voice simply dripped with charm. “You have such a charming house.” He knelt down and kissed her hand. Mrs. Kips pink cheeks flushed red and I was sure she must have giggled. She was quick to recover.

“Please, please, do come in,” she stammered.

The screen door was opened wide so that the tremendous heat of the stove rushed out to greet us in one big whoosh. Six pairs of searching eyes illuminated the dark kitchen. Around a long dilapidated table sat six young children, the oldest of whom was somewhat younger than me. An empty space lay at the head of the table.

“Mr. Kips is collecting firewood,” said Mrs. Kips.

We nodded and sat down. Mrs. Kips hurried to pile the steaming food high on our plates. The large silence was as obvious as an elephant in that room, growing larger with each passing second. The quiet was an all-consuming vacuum that seemed hopelessly insurmountable.

The heat of the stove rose to a peak, though chills ran from the tips of my fingers to the angles of my shoulders and over the capillaries of my scalp, like streams of icy vapor. Outwardly, I smiled at the kind faces and laughed at their jokes but my clammy palms gripped the table edge as my latest breath rattled out of my skull. Mrs. Kips beamed at me and the love expressed in her eyes tied the final noose around my neck.

Then I was climbing the fiery summit of the heatwave, rising above the flames only to be dashed down to their depths. I felt the pain, the pain of the hot embers of my soul coming alight and burning me from within. A pain so sharp and angry, it was as if it had carved out my chest and forced out or stolen my heart. Then this blinding wave surged over me. It racked my body with piercing sobs as all the buried emotions came to the surface. My eyes blurred and smarted with hot tears. In those long moments, the world went dark and I was alone, falling through the fabric of reality. It was like the thin net that had been holding me upright through all those changes in my life had snapped, and now they came thundering down upon me, crumbling like a devastated mountain, tearing down like a vicious hailstorm.

A flash of white and I came to my feet. Miles away, my chair fell to the ground—the noise-like worlds colliding. It splintered as I shattered into a million tiny pieces.

In my mind, I was outside, running. Within the core of my body, I felt the first burning sparks. Then, fed by my madness, the fire rose higher through my body until it consumed me. My eyes burst with the wild, animal flames and a beast within me was awakened. And in my mind, I cried out and screamed and fought, until there was nothing left but the charred ashes. Then all was still.

“You alright, darlin’?” Mrs. Kips’s kindly face dawned like the sun over the horizon of the table. “You been staring at little Caroline for a mighty long time, and you do look pale . . .”

Somehow, thankfully, I found that the English language came to my lips quite easily, and I stammered a reply, “I’m just feeling a bit faint at the moment, thank you Mrs. Kips.”

She smiled a small, sad smile, “Why, let me see if you got fever, you look mighty unwell anyhow.”

Coming around the table she pushed back my stubborn mop of black hairband placed her large sweaty hand over my forehead, as everyone looked on in idle silence.

“You got a real nasty burnin’ fever a-comin’ on; I can feel it all over your for’ead!” she cried, “Mr. Olson, I’m afraid this child needs to rest at home.”

Father turned slowly to look at me, his cold, blue eyes resting on my face. Then, quick as lightning, he looked away.

“Come along, Anna,” he said, his voice like a whiplash. “We better get you rested and well. Thank you, Mrs. Kips, for being so kind.”

I stared dumbly at the floor as my father thanked them and bade them goodnight. Mrs. Kips brought down a basket of food from her pantry and pressed it into Father’s arms. As I was herded through the front door, she called through, “Just a minute! I’ll send young Betsy with you to show you the way. One minute.”

We waited by the doorstep, until a small redheaded slip of a girl ran out. Her round freckled face flushed as she took my hand and shook it firmly.

“Hello,” she smiled eagerly. “I’m Betsy.”

“I writhed in terror from those sickening nightmares,

screaming terribly throughout my sleep.”

I spent the next three weeks imprisoned in my bed, sleeping so deeply and so often that my sense of reality was confused with my vivid, feverish dreams. The days staggered on in sluggish lethargy, until the deathly whistle of the wind on the windows followed me into my nightmares and the spidery cracks on the ceiling were so imprinted in my mind that I saw them when my eyes were closed. My body, suffering in a cold sweat, was smothered in layers of uncomfortable woolen sheets. I writhed in terror from those sickening nightmares, screaming terribly throughout my sleep. And in the small hours of the night, the house preyed on my mind and struck through the fabric of my subconscious attacking my thoughts.

I looked forward to Betsy’s daily visits. She always came with a large basket laden with foodstuffs dispatched from Mrs. Kips’s pantry, and stayed faithfully by my side for several hours, to my immense delight. We quickly became the best of friends. Betsy’s visits lengthened, so that she was present through my frequent and troubled slumbers, changing the cool towel on my hot forehead, and returning home at sundown, her basket empty. Her face became so familiar to me that I knew every freckle swimming along her cheeks and could imitate her melodic, wild laughter to near perfection. She illuminated the building so that the whispering curses of the house dissipated in her presence and my mind was at ease.

I relied so lovingly on the baskets of food, which Betsy would lay out on my bed each morning for me to look at, and which brimmed with subtle delicacies: a string of home-cured sausage, a loaf of warm, fresh bread, a flask of pumpkin squash, a pint of ginger ale, a soft stinking cheese were among the many things that we fondly shared together, me and Betsy, and indeed, the whole household. She was most interested in my tales of the distant city, its bright lights and loud noises, which seemed to me so unimaginably different from the rolling rural atmosphere of Maine with its lush, tonal greens and pastel yellows. She would tell me her stories, in her deep western Maine accent, brushing my hair all the while. In a way, I guess, it was a method to escape my prison. When Oliver wasn’t busy playing with Betsy’s brothers down the hill, he often came to listen, sitting quietly at the end of my bed with a glazed, charmed look in his eye. Although she was younger than me, she was a good listener, which gave me confidence to impress her with my stories, so that soon my tales became our preferred pastime and I strove to provide more.

Through my sickness, Father had almost completely disappeared. In the mornings, he was a recluse, tapping away at his typewriter in the small, dusty room at the top of the house, which he had turned into his study. He would come down to fetch his tray at lunch, which he would eat upstairs. Reappearing briefly in the evening, he’d put on his overcoat and leave through the front door, returning late at night, ignoring me in my bed just a few paces from the gaslit doorway.

The days passed into weeks and my recovery was swift. It came as quite a shock to me that I no longer suffered from illness. I had become so used to my placid immobility in my sickbed, and the way I could see the world spin around me, watching contentedly from my bed like the master of a ship. I had been sleeping peacefully that night, but I now awoke with a sudden resoluteness that pressed me into action. I threw the stifling bedcovers off my body, celebrating the exhilarating freedom of the cool breeze washing over me. My bare feet touched the ground and I was thrilled with a refreshing adrenaline rush that fizzed and surged in me like a burst of fireworks. I ran outside and bathed in the milky light of the moon with my arms reaching high, embracing the night air. Dropping into the long grass, I breathed in the vital incense of the earth. The stars shone brighter than ever before and danced to the rhythm of the earth. I worked my fingers into the warm, moist soil and I felt myself disintegrate into the ground, at one with the living, breathing, pulsating world around me, and I sensed its beating heart and I closed my eyes.

I woke as the first rays of sunlight touched my senses. I sat up. My eyes roamed over my simple soiled nightdress, across the weak legs that had been bedridden for so long and I looked up and saw Betsy coming over the hill, like she always did, swinging her basket as she walked. Her red hair shone like polished copper under the morning sun. Then she saw me. She cried out in shock, until her scream slowly subsided into infectious mirth, and we were both on the ground rolling in laughter.

“You’re—you’re better!” She giggled, as she wiped a tear from her eye. Excitement struck her face “Anna, we have to tell mother!”

I leapt to my feet, only to fall, face first, onto Betsy. We both found this so hilariously funny, we nearly cried with laughter. But Betsy pulled me to my feet and we ran unsteadily down the slope, the sun smiling overhead.

I walked back alone at sunset, steadying myself along the way on tree limbs and on the steep ground in front of me. The light in Father’s study was on, a sign that he was in. I clambered up the steps and decided to surprise him, certain that he would be pleased with my sudden improvement. I made it all the way up to the upstairs landing, when I realized that there was nothing but silence coming from his room. The door creaked as it opened. Papers were stacked high along the side of the room and a crumpled pile of them lay strewn across the floor. The roof sloped in that room, so that the opposite wall was only a foot high; and lined with a myriad of bottles. The typewriter was on the floor by the desk. His desk, a small miracle of idiotic carpentry and one of the only pieces of carpentry found in the house, sat by the large open window, and on it, surrounded by his own debris, was my father. He held his whisky flask tightly in his right hand, but his left hung loosely at his side swaying as he exhaled. His shirt was stained with—was it coffee? And his tie had come undone.

I paused to look at him, the grey-haired, disheveled, unshaven man who snored at his desk, and, not for the first time, I wondered what had happened to him. Had my mother left him because of what he’d become, or had this only come later? I wondered if he thought fondly of the days before he took to drink, back when Oliver was only a small child. I found myself thinking all this detachedly, as if I were an observer, watching on the sidelines. On the armchair in the far corner, was another pair of trousers and his belt. It lay over the wooden arm of the chair, swaying in the stiff night breeze. A cheap, dark brown, leather belt.

It all came back to me then, crashing down on me, shaking the breath out of my lungs.

My father and his raging face, bearing down on me with the belt, its thirteen holes filled with malice, scorching my back with its burning power. The crack of the leather as it flew down, seeking only to punish and destroy, tearing down everything that stood in its path with a lick of its torturous tongue. And I could see it all so vividly in front of my eyes; I, who was penalized for the simple crime of stumbling, chastened for sheer clumsiness, by my father and his leather sword.

But it was all behind me now. And after all, it had only happened once.

I looked down and found my hand was shaking. I steadied the hand, and sat down on the armchair, and very quietly, went to sleep.

I was discovered the next morning by Father, who seemed to be in a good mood. He said that he was pleasantly surprised at my improvement and asked if I would come down for breakfast. I said certainly, to which he replied, good, and then all was quiet after that.

Betsy, who I met halfway down the slope that morning, her face all flushed with excitement, informed me that school was to be starting next week. I wanted so badly to be as excited as she was, but honestly, I dreaded the thought of school. But I wanted to be with her during the day, so I bore a smile until we finally arrived at the long-awaited date.

I walked with her and Oliver along the path she knew so well, under the great pines that lined the route and wished with all my heart that I could hide. We arrived at the schoolhouse, a small wooden building, with big windows and an even bigger bell. As soon as I’d noticed this, the bell began to toll, and all around, I could see children of all sizes arriving. The small crowd of children filed through the open doors. We followed after them, only I fell over onto the doorstep. We were surrounded by children now, who milled around us, peering at me with interest as I lay, school’s first casualty, on the front doorstep. I burned red with embarrassment right up to my very ears. Betsy pulled us inside, where we sat down at the very back. She gave me a smile of encouragement then turned to look attentively at the teacher who had just walked in.

The teacher’s most striking feature was the sternness of her face. A grey face surrounded by grey hair in a tight grey bun. Her brow seemed to be contorted in an almost perpetual frown and she used it to her advantage, frightening the children with one look. She sat down, her electric blue eyes nestled under heavy eyebrows, darting this way and that, and rapped her knuckles against her desk to begin.

She cleared her throat and her rasping voice penetrated her dry, wrinkled lips, “Good morning children, I’m Mrs. Fortescue. Open your books to page fifty-six.”

The sound of stiff pages turning filled the room as sixty pupils searched for page fifty-six.

We came home exhausted and thoroughly drained, but with a sense of accomplishment. I’d grazed both my knees from falling during recess, but I thought of these grazes as my battle wounds. I removed my tired shoes and oozed into the armchair in the kitchen, warmed by the gas oven.

We sat in silence, Oliver and me, until we heard a curious series of noises coming from upstairs. We sat up and listened.

“I’m the fool, am I? Why you—how dare you!” We looked at each other. “I never really trusted you, Desmond; never liked the look o’ you, right from the very start! You’re a damn fool and a coward, Desmond, and you know it! If you hadn’t given me the goddamned automobile, this would never have…” The sound of the receiver slamming down gave me a start. Then there were the sounds of Father’s heavy footsteps as he paced back and forth, and then…the oddest noise of all, the telephone being disconnected, and flung against the wall. Heavy footsteps again. Glass shattering against the floor. I winced. Then silence.

I stood up, only to fall on my knees again. I pulled myself up and went on, leaving Oliver by the oven, so that I could try to understand what I’d just heard.

My falling got worse after that. I felt that I was spending more and more time on the floor and my knees were always bruised a blue-black color. I felt as if these legs weren’t my own, a pair of traitorous legs that gave way when I needed them most. I looked down at them in disgust, repelled by their stumbling nature.

I was at Betsy’s house for the day. I can’t recall what exactly we’d been doing, but I happened to fall into the arms of Mrs. Kips.

Mrs. Kips gripped me by my shoulders and looked me straight in the eyes. We stood there for at least a minute, our heads almost touching. The wind blew fiercely around us, but we stayed fixed, our arms binding us closely together. She spoke gently and under her breath, as if we were sharing a great secret.

“I think it’s time you saw someone about this falling business o’ yours, Anna.” I nodded slowly, suddenly aware that Betsy was watching us. She released her grip and I stepped back, breathing in.

“I’ll call Dr. Summers,” Mrs. Kips said, and with a swish of her skirts, she went through the screen door and disappeared. I looked at Betsy and I knew that the tears in her eyes meant that everything had changed.

It was decided that Dr. Summers would examine me at home. Betsy and I walked back in silence. I sat up in my bed and Betsy resumed her familiar position on the chair beside me, and we waited. Coming in from the kitchen, Oliver sat down on the floor. Father came downstairs, looking a little worse for wear, and nodded to Betsy. It felt like a funeral, and I knew that any minute, Mr. Kips and Dr. Summers would join us.

The door swung open and a leather-clad foot stepped onto the creaky floorboard. His round shoulders in his summer shirt soon followed, along with the white-mustached face above them. Mr. Kips came after him, shutting the door softly, and gave me a gentle wink.

Betsy stood up and offered Dr. Summers her chair, which he took. Giving me a weak smile, Betsy trailed after the others, who were exiting the room.

Then we were alone.

When we were finished with the examinations, he looked at me and his friendly, watery eyes glistened. He cleared his throat and spoke softly.

“Christina,” he said, “I believe it is important that I tell you the truth about your illness. A knot gathered in my throat. “You see, throughout your life, many doctors will tell you that they know what is wrong with you, even if they don’t. I will tell you this, Christina, I have never, in all my forty-four years of experience, seen a case so strange as yours. I’m afraid that it is not polio, as I suspected, my dear child, but something else I really cannot do much about.” His wrinkled hand reached for mine.

“I’m sorry—” He began.

“Thank you,” I heard myself interrupt, “Dr. Summers, for being so kind.”

Then he left.

I wept that night, first in my father’s arms, then far into the early hours of the morning. I wept until the bed sheets were wet with tears and my body ached with sobbing. I wept until my eyes screamed and my throat burned. It was dark and I was frightened. For what I wept, I couldn’t yet know.

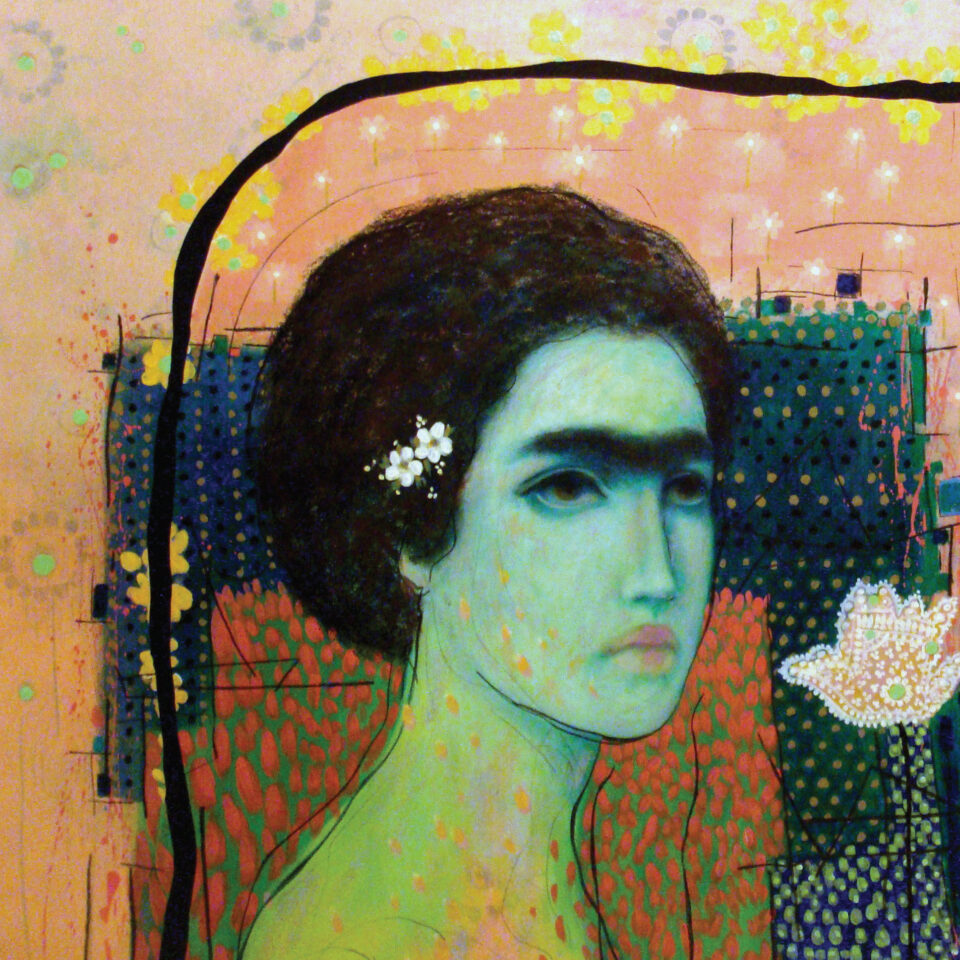

All artwork is courtesy of Eman Osama.