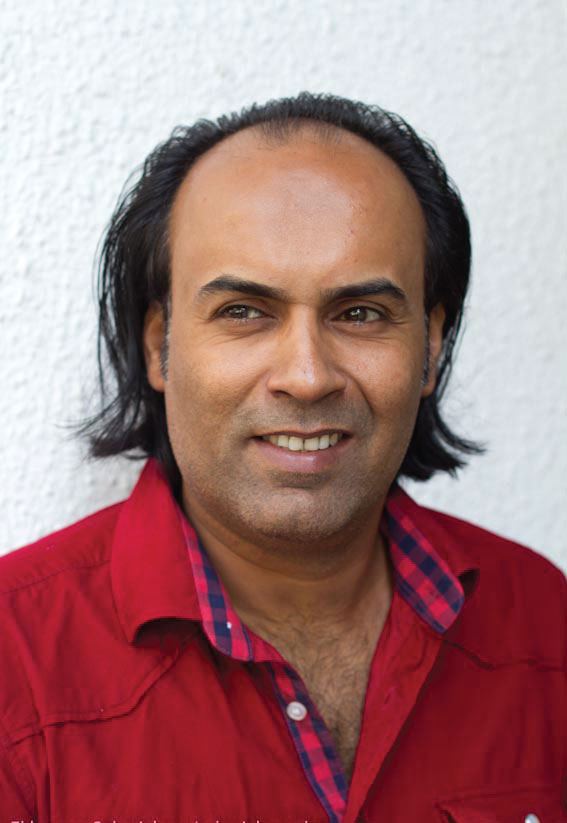

At the beginning of this journey back to Cairo in April 2009, I ask myself: after a twenty-five-year stretch of living in Italy, what will the city of Cairo, its memory, and associations bring about? I feel excited, pleased, but also confused, yet committed to the task. What if, after having become a father and a medical doctor, I discover something from the Other Side, in those territories of inner Cairo that are vivid in my dreams? I was born in Cairo to an Egyptian mother and an Italian father and grew up there, albeit receiving an Italian education, before leaving in 1984 at the age of seventeen. But Cairo has always been alive in my heart, constantly returning in my dreams.

I try to recall memories and associations as if they were impressions of a flaneur in time and space, contemplating flashes of memory that inhabit the man I am today, willing to find and explore an inner dimension. So I say to myself, “Stop. Take—steal—that moment of absolute time. Stay there willingly and reflectively.”

When I first arrived in Milan, I felt I was somehow required to lose part of my soul, and I had already lost my position in the soul of my own city, Cairo. The Egyptian in me was lost in Milan, forgotten. Once, as a young man, I cried when leaving New York at the end of a vacation; I had never been there before, yet as I left, I was already longing for the unknown yet unexpectedly familiar home I had found there. I was looking for my inner Cairo.

When I eventually went back to Cairo, I felt what others, too, have felt: that the city was changing; and what it was changing into disturbed me. I felt estranged from what seemed a harder, more impatient, less tolerant city of endless, ugly new buildings, a place far removed from the Cairo of my childhood. So I asked myself whether this “loss of soul” reflected a real change or a subjective perception of loss due to my geographical, albeit not emotional, distance. I felt Cairo was abandoning me.

This is why I was impressed when I read a poem written in 1911 by the great Greek poet Constantine Cavafy who spent his life in Alexandria. In The God Abandons Antony, [1]C. P. Cavafy, Collected Poems, trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, ed. George Savidis. rev.ed. (Princeton University Press, 1992) Cavafy conveys the instant when Mark Antony stands at an imaginary crossroads between Ptolemaic Egypt and the Roman Empire, more specifically, Alexandria. Antony hears the “exquisite music, voices” of an “invisible procession.” He has been abandoned by his god Bacchus. His luck has failed him, his plans have backfired, and Octavian is about to enter the city in triumph. Antony is princely and dignified; he is a military hero “long prepared, and graced with courage,” and he is about to take his own life. Then, in a brilliant shift of characterization, the city itself—which is etched within him—makes its own voice heard. It is Antony who must depart, and it is also Antony who must “say goodbye to her, the Alexandria that is leaving,” the imaginary receptacle of his own self.

Cavafy evokes the relationship between a man’s self and the soul of his city, unveiling how the soul of a town can manifest itself in a deeply personal individuating process: “the exquisite music, voices” he hears through the window in this crucial moment of his life, are how the god actually speaks to Antony’s heart, where the city’s inner figures have become essentially real. By rising to this higher listening, he overcomes the reductive deception of literalism, “his final delectation” being the ultimate encounter with his human limitedness and the deep emotion of God speaking to him through the sounds of the city. Only then, holding the tension, can he say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria he is losing. This is where I took my cue and stopped questioning myself, because I understood I could listen to today’s Cairo with deep emotion and say goodbye to the Cairo I was losing.

Cairo, My Hometown

Al-Qahira is the Arabic name for Cairo, a feminine word signifying “The Victorious.” It is an immense metropolis of the Third World. A proliferation of cities in the city. A densely populated, multifaceted society of human beings, beyond any reasonable understanding. But still the repository of the memory and soul of old—even ancient—Cairo. We should be careful, respectful when we walk in the city; the soil we tread upon is made of ruins, of those who once were there in other days—their “footfalls echo in the memory.”[2]Thomas Stern Eliot, “Burnt Norton,” Four Quartets (London: Faber and Faber, 1983), p.13. Ancient cities have a depth under the sky.

Man’s reshaping adds layers that go from inside to outside, from heart to skin; under your feet and in your heart are the springs and ruins of your own memory. Natura naturans: houses are the representation man makes of his own soul within the context of nature—that was my heartfelt perception, as an adolescent, of the beautiful buildings of Zamalek, the rich quarter where I grew up, but also an island in the middle of the Nile, a fortunate and envied microcosm in the dense immensity of greater Cairo.

Seen from aboard a plane, Cairo is an interminable extension of a smog-producing, indefinitely expanding organism with a Molochanima.[3]Moloch, “king,” the name of the national god of the Ammonites, to whom children were sacrificed by fire. The city’s soul is here disfigured in an archaic vision. Molochanima is a provocative … Continue reading The immense pollution of Cairo is a cloud suffocating the city, participating in the destruction of the planet, consuming its resources, unsustainable. But the soul of the city is well reflected by my instantaneous sense of belonging. Upon leaving the plane, it is the smell of the air, its warmth, the changes I recognize in familiar places, the feeling tone of the people that resonates with my own, the love I feel for the mere fact of being here, the trepidation and joy when approaching the Nile, the great image of life and its ever-flowing richness.

I felt what others, too, have felt: that the city was

changing, and what it was changing into disturbed me.

The contrast between life and death, with their constant associations, is immediately felt in this city. Contrasts coexist, in my memory of Cairo, with an intensity uncommon to other places, opposing richness to poverty, beauty to ugliness, dogmatism to tolerance, submission to participation. I, therefore, propose to guide the reader through the lights and shadows of Cairo’s soul, which so strikingly manifest themselves in the outer life of this metropolis.

From atop the Cairo Tower in Zamalek, an ugly construction erected by Nasser in the ’50s, you can hear the endless, unnerving background sound so typical of a modern metropolis, made by millions of circulating vehicles. I would call it “the roar of the machine.”

Cairo’s participation in this machine is peculiar, though; it differs from some silent cities of the North in the continuous use of claxons by its drivers; somehow humanized, continuously interrupted by recognizable human modalities of horn-hooting, expressions of impatience, rage, timid intimations to cautiousness, salutations…The human mass fragments itself into the innumerable individual realities, each not wishing to collaborate in the making of this unique monotonous tone, but doing so unconsciously. The dark background sound never stops, however, even at night. Here, we all miss silence, whereas in those neat cities of the North, we miss noise.

Overpopulation

I remember as a child going to visit my maid’s home. She lived in extreme poverty. Many of the families in her neighborhood consisted of more than ten members, but due to the lack of space, they had to sleep in shifts, and there could be no such thing as a private, individual space. I imagine that the relationship to the flow of time may be strongly conditioned by such an intense contraction of private space and by the constant presence of others.[4]“Cairo is, according to the United Nations, the most densely populated large urban area in the world. Overall, this city packs 70,000 people into each of its 200 square miles, confining its … Continue reading

I remember I felt these people’s soulfulness always present in their struggle for survival. The incredible ways they find to answer to their soul’s needs have been wonderfully described by Naguib Mahfouz and Albert Cossery—the latter a French-speaking Egyptian writer, about whom Henry Miller wrote, “No living writer that I know of describes more poignantly and implacably the lives of the vast submerged multitude of mankind.”[5]Henry Miller, Stand Still Like the Hummingbird (New York: New Directions, 1962), p. 181.

Parking a car has become virtually impossible in downtown Cairo. Moving from one part of the city to the other by car is a hostile, highly stressful misadventure. Living in the chaos of contemporary, hugely crowded Cairo has become a daily struggle, threatening physical well-being and psychological balance.[6]“A vast resextensa of throw-away, suburbs, exurbs, divisions and subdivisions; beltways, strip, squatters, squalor, slums, and smog, choked traffic on clogged arteries, and the homeless, the … Continue reading

“No religion in politics and no

politics in religion.”

An Egyptian professor at the American University in Cairo (AUC), Mona Abaza, said in an interview with ABC Radio National:[7]The quotations in this paragraph are taken from Cairo, A Divided City. Images and text by photographer Andrew Turner, and audio by reporter Hagar Cohen, Background Briefing, Australian Broadcasting … Continue reading

The rich ones are trying to flee away. Nearly one million people now live in satellite towns and gated communities isolated from Cairo city. New corporations, IT industry, financial industries have all moved out…a lot of what makes a big city, work, is being shipped out to suburbs.

You might be astonished, but my students have never know anything about downtown, have never even gone downtown, because they live in the Sixth of October or in Rehab, one of those (satellite) cities (made of villas and highly costly meadows in the desert); for me, this is in a way very astonishing because it is as if the memory is being erased; I mean: is the American suburbia being replicated in Egypt?

Today, even the American University in Cairo has moved to one of the new quarters. These districts are built as luxurious residential areas for the rich, in reaction to a legitimate need for air and beauty.

Beauty

There is a huge modern-day risk of confounding beauty and the possibility of creative idleness, (the Roman concept of otium) with luxury and the ready availability of commodities. Luxury (in pathology, luxum, a Latin word indicating dislocation) cannot feed the souls of men, but attracts them. Money “can’t buy beauty” nor love. [8]The Beatles, from the album A Hard Day’s Night, single Can’t Buy Me Love, Lennon/McCartney (recorded at Pathé Marconi Studios, Paris, 1964). By believing that it can, I forget that unique disposition of the heart that opens my soul’s senses and actively resonates, blossoms, whenever beauty speaks to me. This kind of experience is unforgettable. It is a function of man’s heart as the organ of aesthetic perception. Beauty, if one has the “heart” to appreciate it, is inexhaustible, universal, and eternal. However, as Cossery says: “So much beauty in the world, so few eyes to see it.”[9]Albert Cossery and Michel Mitrani, Conversation avec Albert Cossery (Paris: Editions Joelle Losfeld, Diffusion, Harmonia Mundi, 1995).

The prevalence, on a global scale, of pragmatic and materialist values is part of a collective psychic process that has privileged functionality over contemplation, efficiency over reflection, hyperactivity over melancholy, simplification over complexity, comfort over beauty. This phenomenon has been substantially integrated, and sometimes forcefully introjected, by most countries, including Egypt. It is active on a global scale. Techne’s rational regulation of reality and its need to control life to an end, has overwhelmed Psyche and has hidden our soul’s thirst for transcendence and beauty behind a veil of rationality. The tokens of rational knowledge and security often replace bliss in our existence. Have we lost the sense of awe, which is inherent to life itself, which is ourselves? The angel of beauty is within; he is not free like man, he is inscribed in a unique choice, made once and forever—that of breaking the limits of existence (from Latin: ex-stare, to stay without) in order to open out existence to life [10]Umberto Galimberti. Le Cose Dell’Amore, “Amore e Trascendenza” (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2004), p. 22–23. and death. If our gaze is only without, we may not take the risk to live fully and we may lose beauty as a reference for building our houses, our world, and ourselves. The relegation of beauty in museums and in the private domain, in general, has emptied the square. Beauty has deserted the city and has moved inside the palace [11]Luigi Zoja. Giustizia e Bellezza, “Il Palazzo e la Piazza,” (Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 2007), p. 29.

Man may most easily express his hunger for beauty and transcendence in indirect ways, especially if these needs remain unconscious. All sorts of surrogates or substitutes, such as electronic entertainment and consumerism, fill the void. Worldwide, including in Egypt, television is the commonest form of compensation for the absence of beauty and transcendence. The passive or limbo nature of this substitute does not bring growth or transformation, just deeper malaise and alienation in the absence of truly creative alternatives. This may be one reason that people in Cairo are returning to the mosque or church with a moralistic fervor. In others, the same need may deviate towards a shadowy world of perversions, addictions, or crime. Often moralism and perversion coexist. Like many others, I have been struck by the moral degeneration of rich Arabs who travel from the most religious Gulf nations to visit the bellydancing clubs along the Pyramids Road.

The government, with its “neoliberal” attitude, has not guided the planning of Cairo’s expansion in the last few decades. Governmental civil servants consider it a lost battle, and are perceived by the public as dysfunctional, authoritarian intruders. Entire new districts have been built directly by the people and recognized—if ever— only after their actual development, when they connect to the electrical and gas supplies. Streets can often be so narrow as to prevent the passage of an ambulance or a normal car. The sewage system is frequently not even hooked up. And yet, incredibly, all the houses—even those of the very poor—carry parabolic television antennas on their roofs. The expansion of the city has almost reached the pyramids in Giza: more than ten miles of desert filled in by unplanned housing in less than two decades!

Today’s new totalitarian anaesthesia, television— this new dictatorship of ugliness, with its suppression of human feeling through uniform language, the degradation of beauty, the rhetoric of patriotism, the averaging ignorance, the veil of religiosity, and a continuously hungry eye to the market—reaches out even to the poorest, in the most wretched homes of Cairo.

This diffuse and profound poverty affects millions of people who are still hardly meeting the most basic needs, and certainly not the need to be known and recognized. In this context of extreme poverty, the possibility of self-reflection and growth does not exist. But the longing for love and imagination survives—it may be degraded, but is reaffirmed below the level of consciousness. For instance, the kitsch of everyday objects makes endless reference to the eternal beauty of Cairo’s past through color, image, decoration, dress—just walk in the marketplaces of Old Cairo and you will see it everywhere.

As Max Rodenbeck, correspondent for The Economist, writes in his excellent book on Cairo:

Cairo is, after all, the place that endowed the world with the myth of the phoenix. It was to ancient Heliopolis, the oldest of Cairo’s many avatars, that the bird of fabulous plumage was said to return every 500 years, to settle on the burning altar at the great Temple of the Sun and then rise again from its own ashes.[12]“Other places may have been neater, quieter, and less prone to wrenching change, but they all lacked something. The easy warmth of Cairenes, perhaps, and their indomitable insouciance; the … Continue reading

The Economics Of Ugliness

The “economics of ugliness” has reigned in this part of the world since the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, which began on July 23 when a group of young army officers calling themselves “The Free Officers Movement” staged a military coup d’état. Initially led by General Mohammed Naguib, the real power behind the coup was Nasser. It had been preceded on January 26 with what was to be remembered as “Black Saturday” when rioters attacked foreign businesses and targeted British interests—airline offices, hotels, cinemas, bars, and department stores—in particular. Foreign observers who witnessed the burning of Cairo said it looked less like an unruly mob and more like a well-planned and disciplined action.

An anecdote relates the story of the building of the Cairo Tower, a six-hundred-foot column of concrete mesh: It is said that Gamal Abdel Nasser diverted a three million dollar cash bribe to this frivolous construction as a slap in the face to Yankee meddling. This is because the monument’s form has been interpreted by many as Nasser’s “giving the finger” to the CIA.[13]Miles Copeland. The Game of Nations (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1969), p. 174–177.

Moving from

one part of the city to the

other by car is a hostile, highly

stressful misadventure.

Elements of Nasser’s immature psychology mirrored the collective psyche of Cairo in its belief that Israel could be overpowered. Before the Six-Day War, Nasser bragged about Egypt’s power to destroy the state of Israel, and then appeared to have tears in his eyes during his television speech after Egypt’s humiliating defeat by the Israeli army. As Nasser acknowledged defeat, reflecting the people’s despair, he paradoxically diverted their attention from the loss of the war to the possibility of losing their leader when he announced that he was stepping down from the presidency. A mass demonstration demanded his return. The mobs ran out in the streets: their sun was setting, their light was dying! Most revolutions have built into them a yearning for a return to a primeval Golden Age. The archetypal need for the sun and light of the Pharaoh, still alive in Egyptians, manifested itself as a wish to return to the glory of earlier times and to preserve the leader as God. This phenomenon may be related to the docility with which the people of Egypt have always submitted to hierarchy in leadership. The president of the moment identifies with his role and undergoes a process of psychic inflation fuelled by the people’s wish for a strong leader. [14]This may hold analogies with the figure of the Caudillo in South America, which, as shown by Octavio Paz, has its roots in Moorish Spain: “En el centro de la familia: el padre. La figura del padre … Continue reading

Cairo has become an organism of concrete, thanks to the huge demographic expansion and to the work of The Arab Contractors. This began in the 1970s, when the infitah (“open door”) policy under Sadat brought about economic and commercial expansion. The Ministry of Reconstruction was placed in the hands of Osman Ahmad Osman, who was also the owner of The Arab Contractors, a gigantic multinational Arab enterprise.

The repression of beauty as a central phenomenon of our time has triumphed in Cairo as elsewhere. Along with it has come another exquisitely modern phenomenon: the return of millions to orthodox Islam. During the ‘60s and ‘70s, many Egyptians fled to Saudi Arabia for economic opportunity, and then started moving back and forth, introducing what some have called “Petro-Islam”, [15]Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam, “Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism” (London: I.B. Tauris, 2004), p. 61. a form of rigid orthodoxy based on Wahhabism [16]A sect attributed to Mohammed Ibn Abd-al-Wahhab, an eighteenth-century scholar from what is today known as Saudi Arabia, who advocated purging Islam of what he considered innovations. In the early … Continue reading Quite naturally, the average Egyptian gave full consent to the rich and pious outlook of the gulf emigrants, while condemning the immorality of the Western model of modernization.

The Islamic veil has returned. It had virtually vanished in the 1960s when the hope of a new worldview—promoted by Nasser—made the acceptance of a modern perspective possible. The crushing failure of Nasser’s vision of pan-Arab political autonomy and self-determination gave way to a wave of Islamic puritanism. The number of veiled women in the streets of Cairo has progressively increased since then, and nowadays has become prevalent among Muslim Cairene women as well as all over Egypt and the Islamic world.

As previously accurately described by Wolfgang Giegerich:

An equivalent development of a selfsublation[17]The English term “sublation” derives from Hegel’s German term Aufhebung. and rising above itself did not take place in the Islamic world, where continued work upon a critical reflection of its own religion, tradition, social reality has not been undertaken. It has not dissolved the naive, unbroken unity with itself, its participation mystique with its own religion.

The critical fight with, indeed against itself and its own orthodoxy has not taken place. Islam has not attempted to, within itself, distance itself from itself so as to be able to see itself as if from outside. [18]Wolfgang Giegerich, “Islamic Terrorism,” in Jungian Reflections on September 11 / A Global Nightmare, ed. Luigi Zoja and Donald Williams (Einsiedeln: Daimon Verlag, 2002), p. 66–67.

I recall conversations about God that I have had with friends who belong to non-Westernized Egypt. What they constantly reaffirm is the utterly undeniable presence of the Only and Almighty. Atheism is not even conceivable in their minds. Nietzsche’s declaration of “God’s death” is an utterly immoral concept. Differentiation between temporal and spiritual domains is not yet psychologically possible. Although Anwar Sadat posed as a religious president, he became a Nobel laureate for his efforts on the Camp David peace accord with Israel (1978), after which he often repeated the admonishment, “No religion in politics and no politics in religion.”[19]In 1979, Sadat issued a strong warning against religious interference in Egypt’s political life. There must be, he said in a speech at Alexandria University, “no religion in politics, no politics … Continue reading He was assassinated in 1981 by an Islamic fundamentalist group from within the ranks of his own army.

Modernity—and its accompanying individual, existential anguish—is perceived as a great non-entity and of no importance in Cairo. To the Egyptian mind, the Western attitude is a threat to one’s sense of a unified perception of reality and the existence of a spiritual dimension. For Westerners, it is important to remember the grave risk that non-Westerners face in losing a spiritual perspective as a consequence of moving too abruptly from a traditional to a modern outlook. Rapid transition has proved very threatening to the soul of Cairo; a process that took centuries in the West has been condensed and imported from the outside. The West has brought its angst and the functionalistic constriction of the soul.

Thus, to know Cairo’s soul, one should live in one of the poor districts. I, the half-Italian half-Egyptian, who grew up in elite Zamalek receiving a European education, ought to be living in one of the poor neighborhoods such as Shubra, Imbaba, Sayyeda Zeinab, or Bulaq. The sense of obligation to the poor in me points to the great fractures within Cairene society, not only between rich and poor, but also between Nubians and Egyptians, Muslims and Christians, khawagas [20]The khawaga, as my Italian father was called, means Western foreigner, a title of wary respect tinged with ironical contempt. and Egyptians, colonialists and exploited, the government and the people, lay and religious, veiled and unveiled. In the most personal sense, all of this reflects the split between “me-the-half-Italian,” raised in privileged Egypt and Mohammed Atta, the suicidal young man who came from overpopulated Abdeen and led the terrorist attack against the Twin Towers in New York. The split was in Atta as well, although fed with a lack of capacity for integration.

In Search of Cairo’s Anima

An Archetypal Excursion into the Cairene Psyche

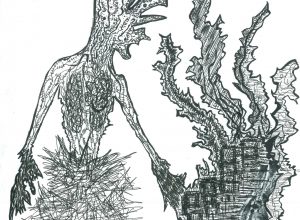

In my images of Cairo—who knows what are memories and what are dreams, what is personal and what is collective unconscious?—violent Egyptian black men and my own children are associated with Sobek, the crocodile god of ancient Egypt. The chthonic nature of the crocodile—long identified with the Nile itself—points to a primitive, reptilian form of instinctual life. Sobek may arouse the call of the “wildness within”[21]This abysmal nature of the Origin is wonderfully described by Rainer Maria Rilke in his “Third Elegy,” in Duino Elegies. Rainer Maria Rilke, Duino Elegies, A Bilingual Edition, “The Third … Continue reading which summons the man who is capable of rising to heroic stature to overcome his own lethargy, the regressive drive that might prevent him from becoming himself. The danger of being sucked in by this drive into the realm of the fierce and terrible mother both challenges a man to overcome his childish dependence and can fuel his fear of women and of his own feminine side. Men in the grips of this fear may rely on a severe, inner authority that of the patriarchal father—who demands an unrealistic perfectionism. If the strict inner father does not take hold, a man must learn to withstand the devil of self-doubt, the temptation to take the easiest way, and carry the weight of ambivalence in enduring his adventure in the world.

Such a man might have to descend, like Osiris, [22]“The Egyptians of every period in which they are known to us believed that Osiris was of divine origin, that he suffered death and mutilation at the hands of the powers of evil, that after a great … Continue reading to the depths (of the unconscious), to the world of the dead where the experience of symbolic death might bring about transformation. The begetting of Horus by Osiris after death is a symbol of the regeneration of life from death [23]It is described in a hymn to Osiris dating from the eighteenth dynasty in the following passage: “She [Isis] sought him without ceasing, she wandered round and round the earth uttering cries of … Continue reading As a child, Horus is known as Harpokrates, “the infant Horus,” and was portrayed as a baby being suckled by Isis (an analogy with Mary). In later times, he was affiliated with the newborn sun. Harpokrates is pictured as a child sucking his thumb and standing on crocodiles while holding scorpions in one hand and snakes in the other hand.

As Harmakhis,“Horus in the Horizon,” he personified the rising sun, as a symbol of resurrection or eternal life. The Great Sphinx at the Giza Plateau is an example of this Horus. Horus will talk to his father and grant him full return, thereafter completing the cycle of rebirth. The myth states that a higher state of consciousness can be achieved and a new relation to the cosmos established.

A fragment from a bas-relief at Philae depicts Osiris in the character of Menu (the “god of the uplifted arm”) and Harpokrates as they sit in the disk of the moon; below is the crocodile-god Sobek bearing the mummy of the god on his back; to the left stands Isis. The process of transfiguration and rebirth into a higher consciousness is here clearly represented. I was moved when I saw this for the first time, for I was then completely unaware of the link between my own images and ancient Egyptian archetypes.

This story shows how images from ancient Egyptian mythology layed below the surface in my own psyche, and arose to meet my soul’s demand for a fuller life. And as the archetypal level of the psyche helped me locate my ancient Egyptian roots, the memory of my greatgrandmother gave me yet more personal, solid ground on which to base my Cairene identity. I have always felt that my great-grandmother incarnated a “genius” of the family, both in her capacity to question deeply and to plant firmly the seeds of new meaning through her creative activities. Huda Shaarawi displayed great wit and a fierce determination of spirit in her quest for women’s liberation in Egypt in the first half of the twentieth century, her political and social activism leading her to become a prominent personality in the growing movement. She became an ardent proponent of reform in the country and in the region, and was the first woman in modern times to publicly shed the veil. She is one of the few women whose name is borne by a Cairo’s central streets.

My great-grandmother’s courageous gesture of removing the veil symbolically set free the feminine potential that had been oppressed for centuries in Egypt and much of the Middle East. Born into an extremely wealthy family in 1878, she might have led a leisurely, albeit frustrating, life, but she adamantly refused to do so. Despite a premature marriage to her senior cousin and tutor, she managed to break out of wedlock and acquire a solid education.

She loved classical music and became an accomplished pianist. She wrote poetry in French and Arabic, and was the author of many articles published in magazines she had founded. Her mentor, the French wife of an Egyptian prime minister, Eugenie Lebrun-Roushdi, helped her become widely read in the literature of the world. Eventually, Huda returned to her husband, by whom she had two children. She joined forces with him on the political scene, where he played a prominent role as treasurer of the Wafd Party (the Party of the Delegation). He became one of the three members of a famous delegation who met Britain’s Lord Wingate in 1919 to advocate the liberation of Egypt from the British Protectorate. When the leaders of the party were arrested and sent into exile, she organized a peaceful protest of women who marched through Cairo’s streets to the British embassy. In 1923, a year after her husband’s death, she began to participate in the International Alliance for Women’s Suffrage (IAWS) conferences. In fact, it was on the occasion of her return from her first IAWS conference that she made her most daring political statement: As she was disembarking in the port of Alexandria, she removed her veil in a spectacular gesture. She was immediately followed in her action by all the women in attendance.

Living in the chaos of contemporary, hugely crowded Cairo has become a daily struggle.

Huda Shaarawi was in her early forties when she set up the Egyptian chapter of the IAWS, called the Egyptian Feminist Union. Many Egyptian ladies and several princesses from the royal family became members and helped her collect funds. She became friends with the members of the Bureau of the International Alliance, who convinced her to join them as a member. She became one of the Alliance’s vice presidents, a position she held to the end of her life in 1947. She spent long years in the service of both organizations, advocating for education and health in Egypt. She helped build regular schools, vocational schools, and hospitals. She founded French and Arab-language magazines promoting women’s agendas. She offered prizes to Egyptian artists and worked hand in hand with the suffragettes of the Alliance. She held a weekly salon in her famous mansion (“La Maison de l’Égyptienne”) where she entertained some of the greatest political and intellectual personalities of her time.

As Iman Hamam states in an article from the English weekly published by Egypt’s main newspaper, Al-Ahram:

Shaarawi threw herself into nationalist politics only to discover that these left women more or less where they had started, the nationalists not being keen to open up the male political monopoly to female competition. Once the nationalist struggle had achieved its immediate aims, women’s concerns and grievances were left untouched and still lying on the table—and this, it might be added, is where some of them at least remain today. [24]Iman Hamam, “The Ladies Protest,” Al-Ahram Weekly (20–26 October 2005, Issue No. 765).

Women in this movement, Beth Baron writes,

Relied on maternal authority and appealed to morality precisely because they had few options for making themselves heard. In spite of two decades of attempting to break into the political system, they had not yet obtained the right to vote, to run for parliament, or to hold office. Writing remained one of their few political weapons. [25]Beth Baron, Egypt as a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007), p.182.

My great-grandmother’s legacy makes me think again of Egyptian myth. In De Iside et Osiride, Plutarch recounts:

The queen sent for her [Isis]…, and…made her nurse to one of her sons…Isis fed the child by giving it her finger to suck instead of the breast; she likewise put him every night into the fire in order to consume his mortal part…Thus continued she to do so for some time, till the queen, who stood watching her, observing the child to be all in a flame, cried out, and thereby deprived him of that immortality which would otherwise have been conferred upon him. [26]Quoted in Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, Legends of the Gods (Charlston, SC: Biblio Life, 2007), p.160-161.

This suggests the paradoxical idea that good is concealed in evil. The wisdom of Isis includes both the light and the dark aspects of the mother, which are needed for the strengthening of life through (the psychological experience of ) death. She thus expresses the wholeness of the psyche, which derives from the coexistence of opposites. Patriarchal societies, especially after the advent of monotheism, have given unilateral consideration of the light aspects of the feminine, thereby exalting maternal unconditional love and virginal innocence. By hiding or denying other aspects such as feminine physicality, the need for independence, and rejecting aspects of the mother, they have repressed them and pushed them aside, in the dark alleys of the unconscious. These natural elements may suddenly resurface with a frightening aura. With this in mind, the “removal of the veil” became an easy-to-understand symbol.

Is it in the richness of Ancient Egypt that other resources can be found—a richness that still lives in the genes and psyches of modern Egyptians, and that might offer ancient solutions for modern problems? Is this wishful thinking? The soul of Cairo is definitely connected to the elements of the earth and to the Great Mother. This is what, in my view, makes Cairenes light and resilient, capable of compensating the harshness of their lives with a great sense of humor. Cairo’s position at the bifurcation of the Nile before the Delta, at the junction between Upper and Lower Egypt, and the self-explanatory fact that Egyptians fondly call their capital “the Mother of the World,” are all elements that point to the positive relation to the Mother in the Cairene psyche. But, with the advent of Islam and with the consolidation of Christianity in what remained of the Roman Empire, patriarchal repression of the feminine worsened. Collective images of the feminine are virtually absent in Islam; the cult of Isis was repressed on all shores of the Mediterranean.

As Iman Hamam reports again:

The only existing statue of a twentieth-century Egyptian woman, among a multitude of male writers, engineers, political activists, and British colonialists, all of whom have their memorials, is apparently that of the singer Om Kalthoum (1904-1975) in Cairo. With a roundabout—where her villa once stood in Zamalek—named after her, and a statue beneath some trees outside the Cairo Opera House, Om Kalthoum’s presence extends beyond musical confines. Indeed, like her male peers such as Saad Zaghloul, Mustafa Kamel, and Talaat Harb, Om Kalthoum gave human form to Egypt’s nationalist struggle in the last century and to women’s role within it. Other women activists, such as Huda Shaarawi and Doria Shafik, and prominent actresses such as Aziza Amir and Fatma (Rose) al-Youssef, also made their mark in the public domain. They, however, await memorialization.[27]Hamam, “The Ladies Protest.”

The great twentieth-century diva Om Kalthoum was beloved by 150 million Arabs, she was the star of the Middle East; to Cairenes she was simply el-Sitt, the Lady. Her funeral in 1975 surpassed President Nasser’s, outpouring over two million mourners onto the streets of Cairo. A national radio station is entirely dedicated to her songs and only comes next to Qur’anic recitation in popularity, even decades after her death. The rise of this woman—born at the turn of the twentieth century into mud-poverty in a Delta village—to unprecedented celebrity could be viewed as a consequence of a compensatory readiness of the people to fill in the void left by the repressed feminine. When in 1960, her voice trembled at the phrase from the song el-Atlal (“The Ruins”), “Give me my freedom / let loose my hands,” she might have directly expressed the longing and the demands of Egyptian women for equal rights [28]Descriptions of Om Kalthoum in this paragraph are freely inspired by Max Rodenbeck, Cairo, p. 328 331. Significantly, a faceless statue of the Lady (who did not wear the veil) has been placed near the Nilometer on the island of Roda, in the garden right outside the museum dedicated to her. The continuing irony is that the statue sits in one of Cairo’s rather hidden spots. A taxi driver complained of how modern musicians are “deforming” her songs, but she is there near the water of the Nile, expressing in the shade the depth of Cairene men’s longing for their anima. The Lady.

Here, beauty has remained associated with the longing for reunifing with the Great Mother, with a participation mystique. I recall deep emotion when, up the minaret of the beautiful Ibn-el-Tulun mosque, I heard the music of the Old City’s awakening, the progressive spread of the singing mu’ezzins’ voices calling out for prayer from innumerable minarets, and extending it beyond, into the City of the Dead [29]The City of the Dead replicates, after millennia, the dead city of Memphis with its line of pyramids, on the other, eastern, shore of the Nile; the cult of saints and patrons (interestingly many of … Continue reading toward the desert, and into modern central Cairo toward the Nile. This phenomenon repeats itself daily. The frame of habit reinforces the sense of the sacred and of beauty. So why is this connection between beauty and its consecration lost to our modern souls? How can we reawaken a modern sense of beauty that connects us to the sacred in the everyday?

Humor may be a partial key to unlocking that door. I once was in Cairo’s medieval center, drinking a shai (tea) at the Fishawi coffee house. After some hesitation, I gave my shoes to a shoe-shiner, who replaced them with a piece of paper under my feet. Before he left me barefoot, I blocked his way and asked him whether I could trust him to come back with the shoes. He smiled and replied that he was the one to worry, because I could run away with his precious piece of paper! This is but one example of Cairene irony, daily renewing itself. Lightness of spirit and a natural propensity for laughter and deflation are a way to open the door, share common humanity, and appreciate beauty in everyday life.

As my half-Egyptian psychotherapist friend, Martin Lloyd-Elliott, put it:

Cairo carries a particular potency in its capacity to evoke an imaginative reaction. I have yet to meet anyone who was indifferent to the city, even if they have never haggled in its souks or wiped the dust off the glass of a rickety cabinet displaying a gold mask. Cairo is a legendary source of the alphabet in our collective imagination because Pharaonic Egypt speaks so vividly to our souls through symbol, starting with those monumental and archetypal constructs at Giza. [30]Martin Lloyd-Elliott, personal communication (April 2009).

Egyptians haven’t forgotten that only hearts as light as the feather of Maat (and today as the shoeshiner’s piece of paper!) will gain eternal life. So I end this journey through my inner Cairo, along the delicate thread of its oppositions, having recovered some semblance of wholeness through narration, with a prayer: “May the words of the Pharaoh (see following poem) bless my soul and that of Cairo with their regal wisdom. Let the Mother of the World have a loving, wise Father by her side in the soul of Cairo and of all Egyptians.”

Amenemhet I (1991-1962 B.C.) On the day of his crowning

Fight for happiness as do worthless men for power and remember that love is the seed and the fruit of joy.

Love others so they may love you and love yourselves, so you may love others.

You will be born fearless because whoever gives you life will find joy in being fertile.

You will fear neither husband nor wife because love will unite you and love breeds no enemies.

You will bear no other fetters than the golden chain of fondness. Family bonds will not unite brothers whose only affinity is of the blood.

You will not fear loneliness since there will never be a lack of friends. You will not fear idleness since the New Egypt has need for idleness as much as work.

You will not fear work because you will find it congenial. You might be born a fisherman and yet become a scribe or, born a farmer, choose to become a warrior.

None will be overwhelmed by fields too vast to till, nor confined by narrow borders. You will not suffer hunger because barns will be filled with bread for the lean years to come.

You will not be afraid of growing, because the years will usher in new horizons. Nor will you be afraid of ageing because you will gain new wisdom at every horizon.

You will have no fear of death, Because you will remember the other bank of the great river, where you will be measured according to the weight of your hearts.

Antonio Karim Lanfranchi, “Cairo: The Mother of the World,” in Psyche and the City: A Soul’s Guide to the Modern Metropolis, ed. Thomas Singer, M.D. (New Orleans, LA : Spring Journal, 2010)

To Edoardo and Guglielmo: may they discover, one day, their father’s Egypt.

My heartfelt thanks to Cristina for her joyful presence and support during this journey across the shadows and the lights of the country of my childhood.

References

| ↑1 | C. P. Cavafy, Collected Poems, trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, ed. George Savidis. rev.ed. (Princeton University Press, 1992) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Thomas Stern Eliot, “Burnt Norton,” Four Quartets (London: Faber and Faber, 1983), p.13. |

| ↑3 | Moloch, “king,” the name of the national god of the Ammonites, to whom children were sacrificed by fire. The city’s soul is here disfigured in an archaic vision. Molochanima is a provocative description of how children in suburban areas are used as “workforce,” their childhood being sacrificed to the Moloch of desperate economy. |

| ↑4 | “Cairo is, according to the United Nations, the most densely populated large urban area in the world. Overall, this city packs 70,000 people into each of its 200 square miles, confining its citizens more tightly than the bristling little island of Manhattan. In central districts like Muski and Bab al-Sha’riyya, the density is 300,000 per square mile, a figure that soars in some back streets to a crushing 700,000. By and large, these numbers throng not tower blocks but alleyfulls of low-rise tenements that differ little from the housing stock of, say, a thousand years ago. In such conditions, with three and sometimes five people in a tiny room, families take turns to eat and sleep. Schools operate in up to three shifts, and still have to squeeze fifty, sixty, or sometimes eighty students to a class.” Max Rodenbeck, Cairo, The City Victorious (London: Picador, 1998), p. 16. |

| ↑5 | Henry Miller, Stand Still Like the Hummingbird (New York: New Directions, 1962), p. 181. |

| ↑6 | “A vast resextensa of throw-away, suburbs, exurbs, divisions and subdivisions; beltways, strip, squatters, squalor, slums, and smog, choked traffic on clogged arteries, and the homeless, the monstrous bureaucracy embodied in numerous buildings of ‘faceless offices of restless despair.’ All of that is also Cairo.” James Hillman: City & Soul, ed. Robert J. Leaver (Putnam CT: Spring Publications, 2006), p. 17–18. |

| ↑7 | The quotations in this paragraph are taken from Cairo, A Divided City. Images and text by photographer Andrew Turner, and audio by reporter Hagar Cohen, Background Briefing, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, ABC Radio National. February 1, 2009, http://www.abc.net.au/rn/backgroundbriefing/stories/2009/2477394.htm. |

| ↑8 | The Beatles, from the album A Hard Day’s Night, single Can’t Buy Me Love, Lennon/McCartney (recorded at Pathé Marconi Studios, Paris, 1964). |

| ↑9 | Albert Cossery and Michel Mitrani, Conversation avec Albert Cossery (Paris: Editions Joelle Losfeld, Diffusion, Harmonia Mundi, 1995). |

| ↑10 | Umberto Galimberti. Le Cose Dell’Amore, “Amore e Trascendenza” (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2004), p. 22–23. |

| ↑11 | Luigi Zoja. Giustizia e Bellezza, “Il Palazzo e la Piazza,” (Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 2007), p. 29. |

| ↑12 | “Other places may have been neater, quieter, and less prone to wrenching change, but they all lacked something. The easy warmth of Cairenes, perhaps, and their indomitable insouciance; the complexities and complicities of their relations; their casual mixing of sensuality with moral rigor, of razor wit with credulity. Or perhaps it was the possibility this city offered of escape in other worlds: into the splendours of its pharaonic and medieval pasts, say, or out of its bruising crowds on to the soft, gentle current of the Nile—even if the tapering lateen sails of the river feluccas did now advertise Coca-Cola.” Max Rodenbeck, Cairo, p. xiii. |

| ↑13 | Miles Copeland. The Game of Nations (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1969), p. 174–177. |

| ↑14 | This may hold analogies with the figure of the Caudillo in South America, which, as shown by Octavio Paz, has its roots in Moorish Spain: “En el centro de la familia: el padre. La figura del padre se bifurca en la dualidad de patriarca yde macho. El patriarca protege, es bueno, poderoso, sabio. El macho es el hombre terrible, el chingón, el padre que se ha ido, que ha abandonado mujer y hijos. La imagen de la autoridad mexicana se inspira en estos dos extremos: el Señor Presidente y el Caudillo. La imagen del Caudillo no es Mexicana ùnicamente sino espanola e hispanoamericana. Tal vez es de origen arabe. El mundo islámico se ha caracterizado por su incapacitad para crear sistemas estables de gobierno, es decir, no ha instituido una legimitad suprapersonal. El remedio contra la inestabilidad han sido y son los jefes, los caudillos.” Octavio Paz, “Conversacion con Claude Fell,” Vuelta a El Laberinto de la Soledad y Otras Obras, (New York: Penguin, 1997), p. 311. |

| ↑15 | Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam, “Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism” (London: I.B. Tauris, 2004), p. 61. |

| ↑16 | A sect attributed to Mohammed Ibn Abd-al-Wahhab, an eighteenth-century scholar from what is today known as Saudi Arabia, who advocated purging Islam of what he considered innovations. In the early twentieth century, the Wahhabi-oriented al-Saud dynasty conquered and unified the various provinces of the Arabian Peninsula, founding the modern-day Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932. This provided the movement with a state. Vast wealth from oil discovered in the following decades, coupled with Saudi control of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, have since provided a base and funding for Wahhabi missionary activity. |

| ↑17 | The English term “sublation” derives from Hegel’s German term Aufhebung. |

| ↑18 | Wolfgang Giegerich, “Islamic Terrorism,” in Jungian Reflections on September 11 / A Global Nightmare, ed. Luigi Zoja and Donald Williams (Einsiedeln: Daimon Verlag, 2002), p. 66–67. |

| ↑19 | In 1979, Sadat issued a strong warning against religious interference in Egypt’s political life. There must be, he said in a speech at Alexandria University, “no religion in politics, no politics in religion.” |

| ↑20 | The khawaga, as my Italian father was called, means Western foreigner, a title of wary respect tinged with ironical contempt. |

| ↑21 | This abysmal nature of the Origin is wonderfully described by Rainer Maria Rilke in his “Third Elegy,” in Duino Elegies. Rainer Maria Rilke, Duino Elegies, A Bilingual Edition, “The Third Elegy” (Evanstone, Il: Northwestern University Press, 1998), p. 35 and 37. |

| ↑22 | “The Egyptians of every period in which they are known to us believed that Osiris was of divine origin, that he suffered death and mutilation at the hands of the powers of evil, that after a great struggle with these powers he rose again, that he became henceforth the king of the underworld and judge of the dead, and that because he had conquered death the righteous also might conquer death.” Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Ideas of the Future Life, (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger, 2004), p.27. |

| ↑23 | It is described in a hymn to Osiris dating from the eighteenth dynasty in the following passage: “She [Isis] sought him without ceasing, she wandered round and round the earth uttering cries of pain, and she rested [or alighted] not until she had found him. She overshadowed him with her feathers, she made air [or wind] with her wings, and she uttered cries at the burial of her brother. She raised up the prostrate form of him whose heart was still, she took from him of his essence, she conceived and brought forth a child, she suckled it in secret, and none knew the place thereof; and the arm of the child hath waxed strong in the great house of Seb.” Budge, Egyptian Ideas of the Future Life, p. 36. Seb, the god of the Earth, has been equated by classical authors as the Greek Titan Cronus or Saturn—meaningfully, the god of patriarchy, later associated with melancholy. See Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy—Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art, (New York: Basic Books, 1964). |

| ↑24 | Iman Hamam, “The Ladies Protest,” Al-Ahram Weekly (20–26 October 2005, Issue No. 765). |

| ↑25 | Beth Baron, Egypt as a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007), p.182. |

| ↑26 | Quoted in Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, Legends of the Gods (Charlston, SC: Biblio Life, 2007), p.160-161. |

| ↑27 | Hamam, “The Ladies Protest.” |

| ↑28 | Descriptions of Om Kalthoum in this paragraph are freely inspired by Max Rodenbeck, Cairo, p. 328 331. |

| ↑29 | The City of the Dead replicates, after millennia, the dead city of Memphis with its line of pyramids, on the other, eastern, shore of the Nile; the cult of saints and patrons (interestingly many of them Shiite, while Egyptians define themselves as Sunnis sympathetic to Shiism) and their feasts (mawlids) have replaced the ancient pantheon. At the great cemetery of Cairo, generations of guardians actually live with the dead, in houses above the tombs. Ceremonies for the burial and preparation of bodies have maintained a lot of Pharaonic tradition. The vicinity of the dead is typically Egyptian, and positively un-Arab. |

| ↑30 | Martin Lloyd-Elliott, personal communication (April 2009). |