I’ve always had a hard time claiming that I’m an artist. When I returned from Paris, after completing my master’s degree in Theory of Arts, not a single family member resisted pointing out that I should be full of ideas, concepts, and creative ideas like my Nene Eliz Partamian. As an aspiring curator, I care about how concepts are presented to audiences, as the word ‘curation’ comes from the Latin ‘care.’ I’m concerned with how the art concept is represented, what medium is used, what is communicated, and how and where it is displayed. So, it wasn’t that I wasn’t embracing my artistic side; I still saw myself as a visual artist, too, but being compared to Nene was suffocating.

There’s a joke between my parents and me, dividing our family into two distinct categories: my mother’s side, who are Greek, Lebanese, and Syrians, who are academics, while my father’s side, who are Armenians, are artists. This leaves me, the product of this fusion, loving both academia and art.

“Your Nene was such a talented artist!” Raffi said with such pride, pointing to her paintings, which were full of life in our home.

There is one in particular that Ma and I love, the one with the modest woman holding her baby in her arms while sitting on the ground. Two pigeons are on the mother’s side, radiating warmth and peace, which is why Ma and I named it Motherhood. Nene didn’t like details; she held back. Instead, she focused on the emotions and essence portrayed by each stroke, with toned colours and composition.

Ever since I was four years old, I called my father Raffi by his first name, which would shock most of my friends as well as my parent’s friends. My father didn’t mind it; on the contrary, he liked that my brother and I called him by his first name. It created an intimacy between us, and we could tell him anything.

“Mother studied alone at the Ecole ABC de Paris and graduated in 1966.” Raffi flaunted Nene’s education and her art at many social gatherings; his voice would deepen and stress on the words “alone” and “Paris.”

His attitude worked, and we all walked around feeling special because of Nene. Raffi was a man of many passions, such as mathematics, philosophy, art, and physics; he had aspired to be an artist himself but never pursued it. Living vicariously through me, he encouraged me to develop my artistic techniques and always turned emotional while attempting to walk in Nene’s footsteps. Maybe his belief in me propelled me to continue my education in Paris, like Nene.

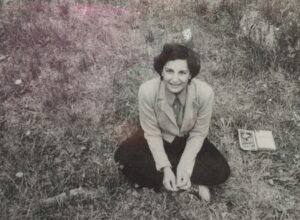

While packing for Paris, I stumbled upon some of Nene’s old drawings and oil paintings. Each time I gazed at the details of the bouquet of deep red flowers set against the dark background, I felt my breath constrict; the contrast made every single petal stand out. Then, I was swept away by the movement of the Armenian dancers wearing their traditional taraz dress; she somehow captured the motion of their performance. I could feel the vibrancy of the dancers, anticipate their subsequent movements and even hear their steps. Looking at these paintings, it was as if, through each brush stroke, she was talking to me. I could feel her presence and her voice, and I could imagine her drawing. Although her images filled my dreams, whenever she spoke, I couldn’t decipher the words; they weren’t clear. I wondered what it was that I couldn’t grasp.

***

In Paris, productivity eluded me. Whenever I forced myself to create, the art turned out dreadful. I could tell it was forced; it stood there bland, emotionless, staring back at me, shaming me for my failure. I would lay on my bed, eyes fixed on the blank ceiling, consumed in frustration.

When I returned home, Raffi consoled me, “When you were a kid, you used to draw all the time, you used to paint, and you used to write.”

These words were a hard reality check; I had lost something precious but had no idea how to bring it back. I sunk into a state of numbness for a while. Buckets of black tar enveloped my days, permeated with the acrid smell of neglected paint and paintbrushes. Silence reigned; no music, no words, and everything I ingested felt spiked by thinners. It was the bleakest period of my life, and I despaired of ever feeling the vibrant strokes of the colour brush against my canvas again. As time passed, I started going to therapy and slowly began making some positive changes. I decided to slowly make my way back to art, since it was the only thing that made me happy.

In search of my old self, I rummaged through diaries, drawings, doodles, photos, even sketches I had drawn over. My desire to find hidden gems of artwork that would reconnect me to myself led me to Nene’s art once more. As I uncovered deeper layers of her art, I realized that this time, it was like she was coming back to me, but now her voice was clear, and it became evident what I must do.

My first exhibition was an installation that narrated our parallel routes, and I played around with the word root. I began to explore my inner world instead of seeking answers externally. In doing so, I discovered countless layers within myself and my background that beckoned for my attention. With the eye of an academic researcher, I interviewed my family, poured over family photos, examined and analyzed every source I could find. The histories of both my paternal and maternal lineages unfolded before me, a painting full of bold streaks of colours, lines, and movements where I was the center, and within all this distortion, it became glaringly obvious how their experiences were similar to mine.

With my renewed passion for art, my dear friend and mentor, Mohamed Abo Gabal, and I were meeting up very frequently to discuss art and our practices. He believed in me and saw the potential to dive deeper into the theme of identity, especially my own.

One day, we sat in a qahwa in downtown Cairo, and he asked me, “Have you ever thought of writing a book about your family?”

This question had been brewing in both of us.

“I would love to, but where do I begin?”

Inspiration was around me all the time. I questioned my identity: I wondered if I belonged to Egypt, was it home? Did I belong with artists or with my friends? Was there something very precarious about believing that I didn’t belong? I asked my family, myself, and even Cairo itself questions like, “How did I come here? Why am I here?” I found the resounding combustions of replies merged into the fact that there was no definitive answer. There were only narratives that kept unravelling as long as I continued to pursue them.

So, I tackled one question at a time, introducing what would eventually become a collection of family and community archives. An exploration of a history I can show and share with the world. These photo albums and stories shaped my family, and I now realized how they have shaped me too.

One of the funniest things I remember about our family history is how my mother, during family gatherings, made a spectacle of how our family came to Egypt and how our relatives are all over the world.

When a relative’s friend asked, “How come you have so many nationalities, Christians, and Muslims in one family?” Every time this question was asked, Ma turned into a comedian, getting up from her seat and poking fun at the circumstances that united us and created this big family.

“How much time do you have, ya ebni/benti? Our family is so complicated; we need an encyclopedia to figure us out!” Mama’s tone was amused and light. She then looked at me and said, “The moment you find a man who can understand your family tree, marry him!”

Even if well-intentioned, these off-hand comments made me wonder why she constantly focused on how we stood out. During my last year at Cairo University, I delved into the full details of our family with my mother. I was writing my thesis on the changing faces of Nationalism in Egypt, where it was required to conduct interviews, and there was this section about foreign communities in Egypt, and the term “Mutamassirun” struck me.

My mother told me the story again, “Both of your great-grandparents fled their homeland due to poverty and persecution from the Ottoman Empire. Your great-grandmother Kokab and her sister were Syrian, and your great-grandfather Zakaria and his mother, Annette, were Greek from the Island of Leros; they all came to Cairo.”

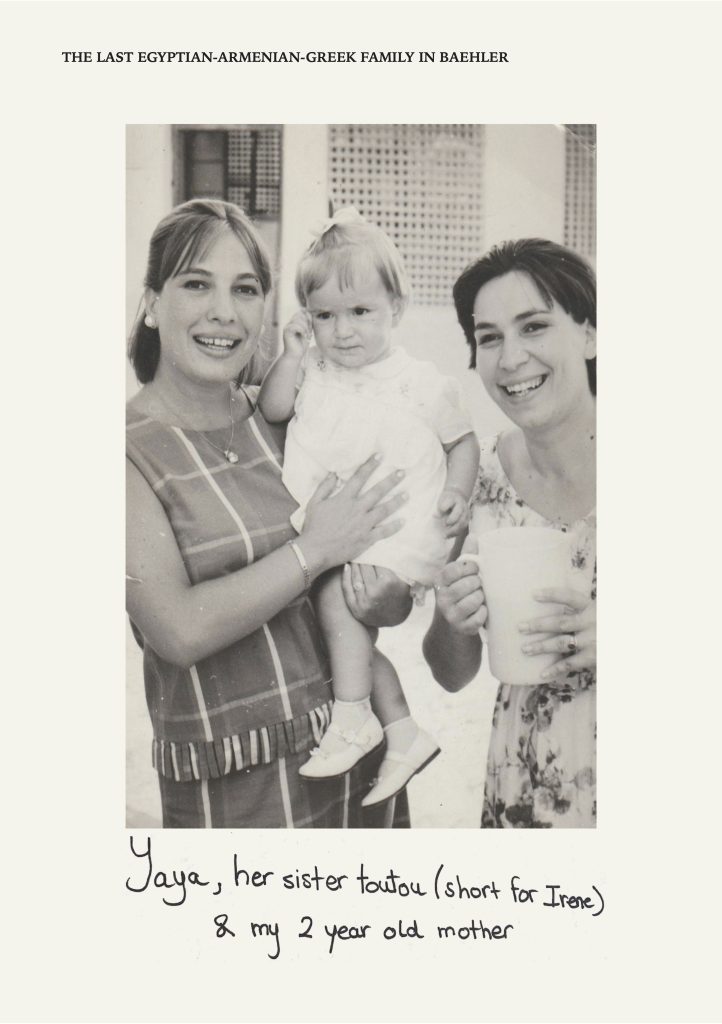

My mother’s passion as she explained her lineage brought us close; I could hear her heartbeats: “They came from different continents, but they landed in the same building, and Kokab married her Greek neighbour Zakaria. They had four children: Irene, Anna, Petro and your Yaya Popi Spathou.”

She held up the photo of the four children, their eyes full of mischief. My mother’s side of the family was more numerous than Raffi’s side, where I would find thirty people gathered during holidays.

“Following her mother’s footsteps, Yaya married her neighbour George Nehma on the 18th of September in 1959. She was on the first floor of their Cairene building in Abdeen, and he, on the fifth floor, was absolutely smitten with her.”

Mama loved this story and I also never tired of hearing how my grandparents met. My Papou George was kind; he was an Italian-Lebanese Maronite and always went to the opera house. My older family members always spoke fondly of him and how he was multilingual, switching from French to Italian to Arabic as if they were all one language.

However, they faced challenges since Yaya’s father, Zakaria, was a conservative Greek Orthodox. Papou and Zakaria insisted the couple marry in the Greek church.

Picture this: a couple, trailed by guests and family, running from the Maronite Church in Shoubra to the Greek Church in Hamzawi, and finally performing a civil marriage. Their wedding day unfolded like a comedy scene from a movie. On that day, they were married three times.

My mother told me that Yaya and Papou had two children, my uncle Jean-Mario, the older son and my mother Angela-Marina, the younger sister. The Nehma family lived in Abdeen and later moved to Bab Al Louq. They left Abdeen because the community was changing; most of the mutamassirun, which is what foreigners living in Egypt were called, left the district, and the building was slowly losing its allure. They lived on the fifth floor; the elevator wasn’t working, and the building administrators refused to fix it. During the same time, Yaya’s sister, Anna, was moving to Greece, and she had an apartment on the third floor in Bab Al Louq, which was in a much better neighbourhood. She also had an elevator that was working! And that’s how the Nehma family abandoned Abdeen for Bab Al Louq.

It was typical for the Syro-Greek communities to attend French missionary private schools, often subsidized by the church and part of the French colonial legacy in Egypt. Mario attended the boys-only College de La Salle, while my mother attended Sacré-Coeur Ghamra, the girls’ school where Yaya was a maths teacher and provided private tutoring.

Yaya and Papou remained happily married for ten years. Sadly, he passed away due to tetanus when my mother was just five years old, leaving Yaya as the sole caretaker of her family. After his passing, friends suggested that Yaya enrol her children in the Greek school, which would be more affordable. The family faced an issue with their names; they didn’t have Greek names as they had taken their father’s last name, Nehma. The dean told them they needed to change their name to Yaya’s family name, Spathou, to get accepted into the school. Yaya refused; she was determined to preserve her late husband’s name as a perpetual reminder to her children of his legacy.

Listening to this story was bittersweet, as it showed how one can preserve memory and heritage within a name. While researching Armenian-Egyptians, this reminded me of an online article about Fouad El Zahery, the famous composer. His real name was Fouad Garabed Panossian. He had changed his name to Al Zahery because he lived in the Al Dhaher district, and he wanted to eternalize his love for his district in his name, but I wonder, in doing so, he was also erasing his heritage. Yaya kept her children’s names to keep Papou’s memory alive. Still, I wonder what El Zahery lost in changing his name, and it makes me think of all the actors and actresses who adopted Arab names, erasing their Armenian identity, for career advancement or maybe inclusion?

“Until this day, I am in awe of what your Yaya did for us. She was a strong-willed woman who loved your Papou so much. She never wanted us to forget him; she always wanted us to smile when we remembered him,” Mama said.

This time, my family history registered; maybe it was because of the articles I’d read, maybe my grade on the line, or maybe the passion and hurt in my mother’s eyes as I held her hand in this intimate one-on-one setting. I had never realized how hard her life had been. Both Yaya, a single mom, and my mother, losing her father at such a young age was a trauma.

***

When I mentioned researching Armenian-Egyptians, I was trying to figure out the history of Armenians in Egypt in parallel with finding more information about my Armenian side. As if my mother’s side wasn’t complicated enough.

At school, in history class, I learned about the Armenian genocide in 1915, and the whole class turned to look at me. Of course, as a child, I didn’t know how to respond. All I knew was that my name differed significantly from my friends and classmates.

I remember asking my parents, “Why are we in Egypt? We look different, and our names are different!”

They always answered in unison, “Because we are Egyptians, not by look or name. We are Egyptians.”

When I got older, that history lesson about 1915 remained with me. I asked Raffi, and he trusted that I could finally handle knowing the details. I found out that my great-grandparents, with my Dede,[1] fled the Armenian genocide and found refuge in Egypt. My Dede’s name was Gregoire. He was born in Turkey, and his family spoke Turkish, Armenian, French, and English; later on, they’d learn to speak Arabic, too, as his whole family was displaced and settled in Alexandria.

Dad told me, “Your Nene was luckier as she was born in Cairo. Only her parents witnessed the horrors.” He got emotional; tears filled his eyes as he continued, “Not only had my grandparents witnessed the killings and persecutions, but my grandmother Kohar lost her brother Assadour along the way.”

I was utterly shocked, and although his chest was heaving, I asked him to continue, “There are many gaps in the story; these gaps were transposed to our lives. It was only years later that he was found. My sister Nairy visited him in Armenia, and they took a picture together; I never had the chance to meet him.”

Raffi never met his uncle; the story of his disappearance was and still is quite a mystery in my family. I still struggle with trying to find out the truth, connecting the missing pieces while being mindful of my parents’ emotions and everything they have had to surmount to make our lives and our home in Egypt.

From my parent’s stories, it was clear that I had no Egyptian blood whatsoever. This saddened and confused me. Did blood matter? Could I still claim to be Egyptian like my parents do without having Egyptian ancestors? Did I belong to Armenia, Greece, Lebanon, Syria and Egypt? To all of them or to none.

I thought I was the only one having these feelings because my anxiety made me believe many times that I was alone in my struggle. However, when I sat down with my brother, Azad, to ask him a couple of questions about this book, he reminded me of how he had the same thoughts when he was eight. The memory returned to me, and I could hear his strident voice and feet stomping our wooden floorboards.

“I want to change my name! I hate it! People keep mispronouncing it and making fun of it!”

Upon seeing this tiny, angry human, my mother chuckled and hugged him; she then gently said, “Azad means free in Armenian, and we chose this name because we love you and we want you to always have this free spirit. People don’t understand your name because they don’t understand your story. Your name is part of your story, and you will realize that one day.”

My brother was quiet for a moment, but then he fidgeted and shook his head unconvinced.

My mother smiled and said, “Worst case scenario, if you still don’t like it, you can change it once you’re eighteen.”

This last statement had appeased my brother, “Mom really knew how to deflate your tantrums,” I said.

“I’m a bit ashamed of how much I resented them for my name,” Azad said. “I can’t imagine not having an Armenian name. I wonder what we will name our kids.”

“If we have kids!” I retorted. At nineteen, he had become my best friend.

***

I talk about my Nene a lot; she was the inspiration behind my first art installation and my first exhibition. Nene participated in various group exhibitions and had solo exhibitions in Egypt and abroad. She also held private lessons, and one of her dearest students, Kegham Djeghlian, is Palestinian, Armenian, and Egyptian. Kegham has handsome features, is tall, has thick eyebrows, and has a chiselled jaw; he’s named after his grandfather Kegham, Gaza’s famous photographer.

Raffi says, “My mother used to adore Kegham; when he was a child, she used to hug him and place him on her lap.”

I asked Kegham about this and met him frequently at the club. “Your Nene was my first art teacher, I will always remember her.” His eyes glistened, and I wondered if I would ever have such an impact on another human as Nene did.

Nene’s solo exhibition at Goethe Institute was inaugurated by the famous Armenian caricaturist Alexander Saroukhan. A man who drew more than 20,000 caricatures. He stood out as Egypt’s most renowned caricaturist, contributing to the leading papers and magazines Akhbar El Yom, Akher Sa’a, and Rose Al Yusuf. He was known for his distinctive style, and Saroukhan perfectly depicted the subjects in his caricatures.

Raffi told me that he made a caricature of Dede holding scripts of plays and musical sheets. Indeed, that was true. My Dede was an opera singer known for his baritone voice. I faintly remember his routine; he would sing in the morning, his booming voice would flush out all sound, and then he’d have breakfast and head out to meet his friends at the Gezira Sporting Club. In the afternoon, he made a point to cross town to visit his community in the Armenian Club in Heliopolis. As if that wasn’t enough to fill a day, he dressed in his most elegant suit every evening, spraying really dense perfume to sing at the Opera or attend plays there.

Nene’s accomplishments continue to motivate me to carve my own path in art and continue producing. I noticed in my recent drawings and installations that they are adorned with flowers or related to flowers in one way or another. I hadn’t thought much about it. However, looking back, I realize that it all made sense. My use of flowers in art was borrowed from Nene, from all the paintings in my house of the many types of flowers. Her favourite was the chrysanthemum. It may be unconsciously borrowed from the Forget-Me-Not, the flower symbol of the Armenian Genocide, a beautiful yellow and light purple flower. It also might be borrowed from the fact that these flowers stem from seeds that have bloomed everywhere, like my family. Perhaps, flowers were always embedded in me; I only had to look closer.

[1] Grandfather in Armenian.

Photos Courtesy of Melanie Partamian