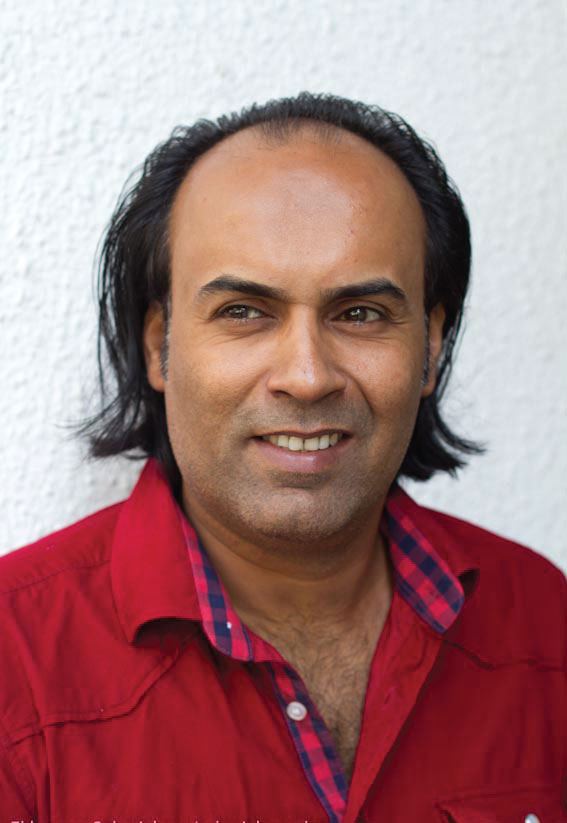

An interview with Ahmed Saadawi

Ahmed Saadawi is a man who believes that one should never stop asking questions even if it isn’t always possible to get clear answers. In his latest award-winning novel Frankenstein in Baghdad, we find him digging deep into the human soul as he explores questions of innocence, guilt, and redemption.

Saadawi was born in Baghdad in 1973. At the age of twenty-seven, he published his first book of poetry, Anniversary of Bad Songs (2000), followed by two novels, The Beautiful Country (2004) and Indeed He Dreams or Plays or Dies (2008). In 2010, he became one of the thirty-nine participants in Beirut39[1]Beirut39 is a collaborative project between the Hay Festival, Beirut UNESCO’s World Book Capital 2009 celebrations, Banipal magazine, and the British Council, among others, and aims to identify … Continue reading, a Lebanese initiative that shed light on the best up and coming Arab writers under the age of forty. Beirut39’s pool of writers’ work was later translated into English. Saadawi is not only a poet and a novelist, he is also a screenwriter, a writer of children stories, a documentary filmmaker, and an occasional cartoonist.

In 2014, he became the first Iraqi writer to win the International Prize for Arabic Fiction—supported by The Booker Prize Foundation—for his novel Frankenstein in Baghdad. The novel is set in the years 2005 and 2006 and kicks off by introducing Hady Elattag, a filthy rag-and-bone man, who collects body parts of victims who died from explosions and stitches them to form an entire new body that can be buried. A lost spirit finds a stitched corpse, haunts it, and brings it to life.

And so the story begins…

Saadawi’s great accomplishment wasn’t merely in writing an exquisite story, but in developing a vivid fantasy scene and turning the spotlight on Baghdad’s anguish during the civil war. This makes his novel one of the most memorable works of contemporary Arabic fiction.

AB. What inspired you to write Frankenstein in Baghdad?

AS. Different elements and events inspired me to write this novel. During Baghdad’s civil war, I was a journalist and had the opportunity to visit the morgue, where I saw someone asking about one of his family members who had been killed in an explosion earlier that day. One of the workers in the morgue coldly told him, “Go in there, collect a body [referring to the remains and the body parts of the people killed in the explosion], and take it with you.”

AB. Amidst this atmosphere of war and violence, what made you choose the topic of “morality and crime”?

AS. Because morality and crime are inevitably related to one another. And that no one leaves his or her home aiming to kill someone without the excuse of defending a moral principle. No killer will admit that he or she is a criminal; they believe that they are noble soldiers fighting for a cause, a cause to help their group, race, neighborhood, or even their political and ideological league.

So, by discussing a brutal murder, we find ourselves directly debating what really caused such a catastrophe to happen. And consequently, we see how the different moral standards that criminals adopt could lead to civil war. It also shows how we take part in this cruel circle of violence, either by instilling and nourishing the fears of others, by supporting these killings, by accepting them, or even by stepping back and taking no positive action.

AB. Can you tell us more about the stages of producing Frankenstein in Baghdad?

AS. In July 2008, an excerpt was published on Kikah.[2]www.kikah.com is a bilingual online Arab literary magazine, no longer in operation. I’ve been working on it since then. During this period, I wrote three drafts, interviewed different people, and did a lot of research. In the final stage, I had to quit my job and be fully dedicated to this project for a total of eighteen months. Finally, I reached a point where I was satisfied, and I finished writing in early 2013. By that time, I had consumed all my savings, and I had to start looking for a job again.

AB. Your narrative style is quite cinematic, which makes it distinctive. You narrate the events through the different perspectives of the characters. Why did you choose this style?

AS. I keep experimenting with different narrative styles until I find a style that suits the plot. The way Frankenstein in Baghdad is written is the best way that could be used to express the ideas of the novel. It allowed me to illustrate the different characters existing in Baghdad society. It was essential to give enough space for all the characters, as each one represents a social category in the specific time frame in which the events take place.

AB. What obstacles or challenges did you face while working on this novel, and how did you overcome them?

AS. The challenges I faced are the same any writer in any part of the world faces. It’s hard work that takes time and requires a stable mood. Working on a book is not easy for many writers, as we find it hard to be isolated from everything going on. Besides, trying to control one’s life and dedicating time for writing is quite challenging.

I took the risk by setting aside time completely dedicated to this project, but I am not sure that every writer can do the same. It consumes a lot of money, and one can never guarantee the result. Add to that, the danger of living in a city threatened daily by violence, fear, and insecurity, with inadequate local facilities. For writers to be able to continue writing, they need to isolate themselves and stay in their own bubble to dream and think.

AB. If you go back in time, would you change anything about this novel?

AS. I definitely wouldn’t. I gave this novel too much time, effort, dedication, and research. I had to critically judge every detail. If I go back in time, I might fail to reach this level, because a part of the process is what happened while I was writing, all the events that inspired me. I can never guarantee that everything would happen the way it did.

AB. Did you expect to win the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) and what does it represent to you?

AS. I believed in my work, I believed that it was one of the best novels participating in the IPAF. It represents a good opportunity; it was a chance to see my work under the spotlight, and it helped promote it and made it possible to reach a wider audience. But I am still halfway through the journey; it could be tempting for readers to buy a winning novel, but then they might discover it’s not really that interesting. At the end of the day, the real judge is the reader who will either feel connected to the book and consequently trust the writer, or dislike the book, the writer, and all his future novels. I’m so lucky to have gained this trust from a wide swathe of readers in the Arab world.

AB. How do you deal with criticism?

AS. I try not to be distracted by people’s criticism. However, I appreciate all the opinions I got about the novel, both positive and negative. They have helped me evaluate what I did, and made it easier for me to set a new goal.

AB. What about your experience as a writer living in Baghdad? And did you ever think of leaving?

AS. I am just like any Iraqi citizen living in Baghdad; I feel depressed at times and think of running away to another city, or another country even, which would be possible to do as I have some opportunities. Then I sit back and just wait for things to get better, with the hope that circumstances will one day be ideal for me.

I can’t emigrate for example, even though it makes sense, most of my friends have already done that. But I can’t because then I will lose communication with the people I write about. However, different events are taking place, which might make me change my mind.

AB. Do you see yourself more as a poet or a novelist?

AS. Currently, I’m more prone to write novels, even though I still write poetry. But I feel most readers see me more as a novelist, so I am directing my creative energy toward that. There are many great active poets on the Iraqi literary scene, but our achievements in novel writing are still few …I hope I can leave a mark in this field.

AB. What do you do when you are hit with writer’s block? And how do you overcome it?

AS. I’m a writer who never finds enough time to write; writing is not easy for me. It is a technical job, one has to hone and develop their skill. Also, it needs a clear mind and a certain atmosphere, which are usually interrupted by our daily routine. Besides, our daily life goes against fantasy writing. So, one has to believe in it, be passionate about it, and dedicate enough time and effort. Achieving that demands a great deal of self confidence, hope, and audacity. If we don’t steer away from our daily hectic lives, writing will always be difficult, even if you open a blank page and sit there, pen in hand, waiting for hours.

AB. Who are your favorite writers?

AS. A lot of international, Arab, and Iraqi writers have impressed and inspired me. It is difficult to name just one favorite. However, I love Abdul Rahman Munif, Abdul Hakim Qassem, and Mohammed Khudair. From the international scene, I admire William Faulkner, and of course, Gabriel García Márquez, among many others.

AB. What are you currently working on?

AS. I am working on a novel called The Uncertain and Last Journey, which I have mentioned in Frankenstein in Baghdad. I am not sure when I will be able to finish it though. New editions of some of my previous novels will be released sometime this year in addition to a book of short stories and another book of poetry as well.

AB. What are your thoughts regarding censorship in Iraq or in the Arab world in general?

AS. Censorship is ancient history. In this digital era, there is always an open source of information, and it just doesn’t suit this modern spirit anymore. It astonishes me how some Arab countries still follow this dictatorial technique. They ban any method of cultivation that disagrees with the authority’s political beliefs. These methods and techniques have never been successful and never will be. It is ironic, actually.

A simple example is [Salman Rushdie’s book] The Satanic Verses, a novel that was banned in most Arab and Muslim countries; yet, it can be found easily online. Another example is when the Iraqi government banned all social network sites a few months ago. On the very same day, young people were able to log in and criticize this stupid action.

We can’t develop if we don’t read.

AB. What do you think of the literary movement in Iraq and the Arab world? And how can it be developed?

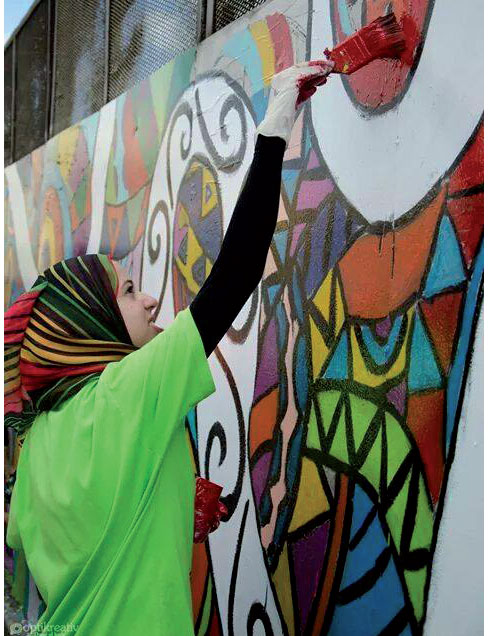

AS. I believe it is great; there is always new blood adapting itself to the circumstances, no matter how bad they are. Writers have the drive that urges them to achieve something, which is enough proof that they are fighters, passionate people that never despair, despite the difficulties surrounding them.

To develop our literary status, we need to establish entities that promote reading and writing, to open new markets and sell books everywhere. We need to make it possible for everyone to read. We can’t develop if we don’t read.

References

| ↑1 | Beirut39 is a collaborative project between the Hay Festival, Beirut UNESCO’s World Book Capital 2009 celebrations, Banipal magazine, and the British Council, among others, and aims to identify thirty-nine of the most promising Arab writers under the age of thirty-nine. Held in 2009–2010, it followed on the success of Bogotá39, held in 2007 to identify the most promising young Latin American writers. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | www.kikah.com is a bilingual online Arab literary magazine, no longer in operation. |