Again she got up after the sun had come up, almost forty minutes after the alarm had rung. And again she leapt off her bed and flipped on the lights, shook her little brother and sister awake and told them to go put on their uniforms and brush and get their shoes on. The children, used to these kinds of mornings, fell into sleepy, routine steps, taking turns for the bathroom, rubbing their eyes, picking up their backpacks. Saba changed in the kitchen. There was evidence of their older brother Imran in that space, who’d left for work at three in the morning, the rubber band on the side of the plastic packet of bread, the cup of tea by the sink with a spoon in it. Other signs of his presence were the children’s ironed uniforms on hangers on the bedroom handle, and their lunch boxes and water bottles in the kitchen. Saba rushed them out of the apartment, down the stairs and into their car. We don’t want to go to school, Baji! the children said, small backpacks strapped to their backs. Noor’s was blue with a Power Ranger on it, the colors bleeding just a touch outside the lines but not enough for him to notice or care; Amna’s was green, silver stars on the front, which, last month, she had colored golden because she wanted a green-and-gold backpack but didn’t want to ask her older sister for a new one. But the golden marker hadn’t stayed for long. And Saba had asked if she wanted the silver back, and the little girl had nodded and shrugged. Then the older sister had stayed awake till late, using soap and water, which hadn’t worked perfectly, but at least the silver was more visible again.

‘Oh but you have to to go school,’ Saba said to them now, ‘your friends will wonder where you are. They’re already wondering anyway, because we are so so so late.’

‘If we are so so so late then a little bit more late won’t matter,’ the little sister said, who was older than the youngest one, therefore better at the art of negotiating.

Saba moved the car between other impatient vehicles on the road. If only she hadn’t overslept. But she was so tired all the time, and it was so hard to stay awake after fajr, and that hour between then and six was when her sleep was the deepest and sweetest, not even dreams intruded then. Now the children’s principal was going to want to speak to her, she was going to teach Saba about responsibility, and how to be a parent in the absence of living parents.

Ahead, the main road was about to split into two. The left one curved away, hugging a line of shops and brick homes. The right one went up toward the Netty Jetty Bridge, which led all the way to the children’s primary school, two squat buildings painted a cheery blue, one for boys and one for girls. This morning there was no traffic going toward the bridge, but Saba didn’t pay much attention to that. Her mind was on the route she would take to get to her work, trying to work out alternative ways so she wouldn’t be too late. She was a secretary at the head office of a local candy company. People liked seeing her in the office before them, as if she were warming up the place for them. The grace period after the death of her parents had faded not too soon after the event, now nobody spoke to her in a lowered voice or asked about her little siblings. More importantly to her, her boss had begun to warn her about her lateness.

It was only when she got closer to the bridge that she saw the police vans on either side of it, and realized the area must have been cleared of traffic and pedestrians, maybe because of a visiting dignitary’s scheduled cavalcade or because they had to catch somebody.

The policemen standing by their vans stared at her speeding car, then got into a van and began to follow, but she only saw the glorious grey of the road of the bridge. They were on it now, and she wasn’t going too fast, but she felt as if she were rushing. The children in the back were laughing and saying, “The police is coming! Go faster!” They were in the chase seen of a movie, they had broken free of the ordinary pull of their lives. She glanced into the rearview mirror and saw flashes of the children’s hair and faces and teeth.

And her thoughts jumped to the day when she, Imran, Noor and Amna had been at home at the same time, no one was at work or at school, and she had convinced Imran they needed to buy a can of gold paint. They had covered their younger siblings’ faces and hands and arms with it. They’d painted their clothes gold as well, and the children had practiced being solid-gold statues on the footpath outside the apartment, and even inside the park at the corner. They’d slept late that night and woken up long after her alarm the next morning. She’d had to hurry them into the car and had decided to take a shortcut. Keep sitting, she’d said in the direction of the backseat, almost in a yell, throwing her head back over her shoulder then whipping it around again. She’d turned the steering sharply toward the right, straight onto the large brown field where boys and men played cricket on Saturday nights and Sunday afternoons. But on that weekday morning they weren’t playing, they were walking, toward the bus stop on the other main road or maybe toward nowhere. She didn’t notice the earth rushing out from beneath the tires; and if it slowed them down, she didn’t feel that either. The field was large, there was nobody in her way. If someone heard the sound of the car and turned to look at the phenomenon of an old white Toyota Corolla throwing up clouds of earth on the roadless field they moved farther away while still walking and staring, and sometimes smiling in an amused way, pointing, gesturing. Who was this girl driving this beat-up old car, a taxi but painted white, did she forget where the road was? they thought. And she carried on, she was committed toward getting to the end of the field. Her little brother and sister were chattering excitedly, and then they began to shriek with laughter, and that was excellent, it was what she had wanted. When she arrived at the end of the field she revved through the gravel and onto the main road.

And she remembered a Sunday morning after that when she had woken up Noor and Amna. The sun was just coming up and they were confused, it wasn’t a school day. She told them to be very quiet and follow her. They walked behind her, bits of gold paint still left over on their earlobes and the backs of their necks. They got into the car, and she took them to Sea View. They sat on the low brick wall and looked at the quick grey waves. Afterward she bought them sandwiches and gummies, and watched the water and watched them eat. Her little brother held his pack of candy carefully so it wouldn’t fall into the sand. He knew how to make his treats last. If he got one he waited until six in the evening when he sat on the sofa and took one piece out, pinching the ends and stretching the gummy as far as it would go, before finally eating it in small nibbles, starting from the end up. Her little sister was small for her age. She wasn’t crazy about treats. What she was into was careful observation which included making sure her little brother crossed roads carefully while holding her hand or that of an older sibling’s; watching Saba or Imran’s hand gestures when they talked; doing her homework extremely neatly. Saba sat on the wall next to them and thought of ways to get rid of the paint; the children’s class teachers had sent them home with notes of admonition about uniform and appearance.

So often she tried to take them off course, but it took no time before they were back to negotiating the hours of the day, negotiating roads, negotiating costs, negotiating living. Already the drive across the field was old, as was the gold paint, and it felt so long since they had flung themselves toward anything. Already they had forgotten what freefall was.

So she took the three of them into a horizontal freefall. What they all needed, Saba thought on that bridge, was a hugely joyous wrenching moment in their lives. Not a gentle forgettable one or a series of them, but a complete change in direction the way a person in a movie turned the car’s steering wheel suddenly to the left or to the right, grunting, teeth gritted, desperate to get away from the villain. The bridge was empty, they were the only commuters on it. On her right was the sun, and on the road below the usual traffic of the morning. She heard Noor and Amna shriek with laughter and say, ‘There’s the police! Faster, Baji!’ And she had to smile too. There they were, caught in the sun up on a bridge, tearing away toward something.

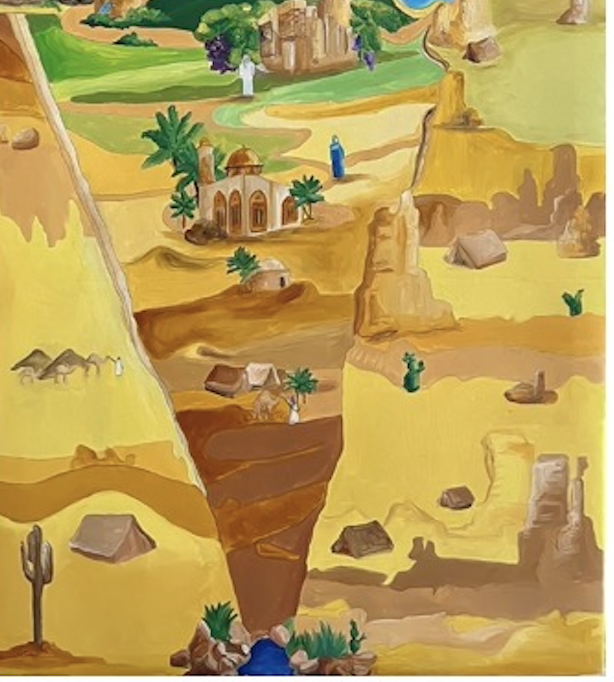

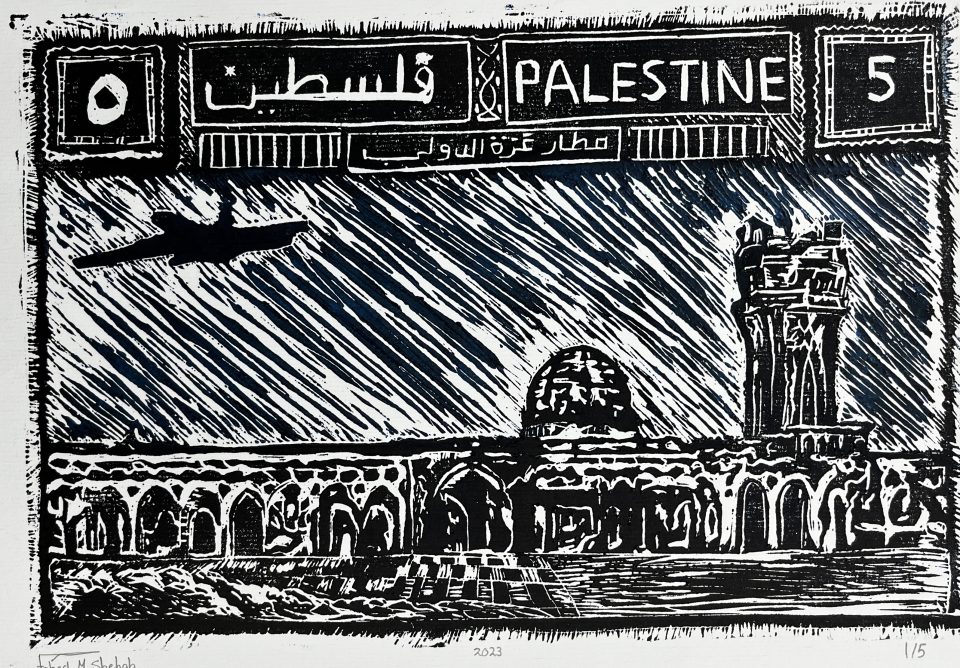

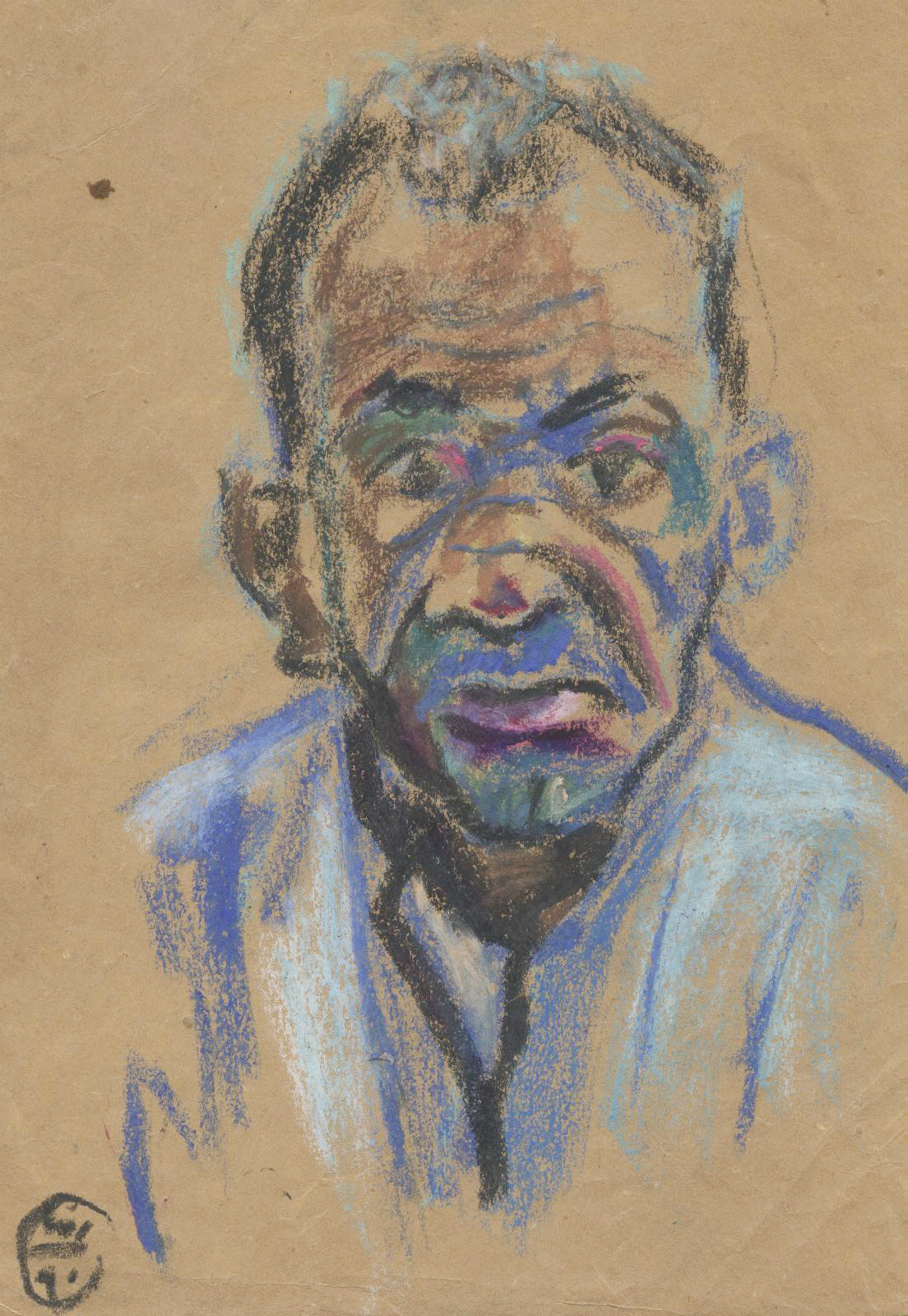

Painting Courtesy of Our Featured Artist Fahed Mohammed Shehab