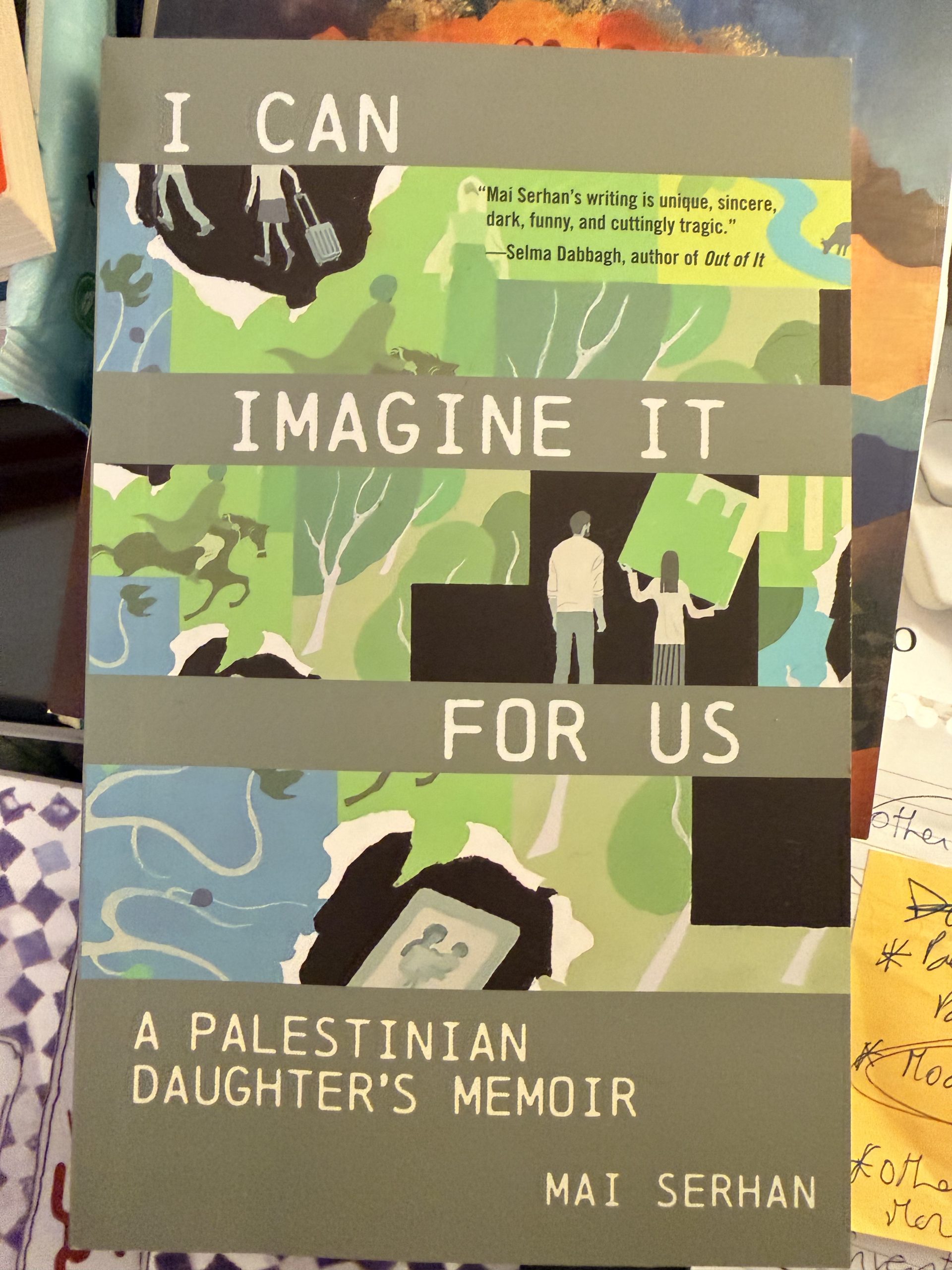

Review of I Can Imagine It For Us by Mai Serhan

I had been waiting a long time for Mai Serhan’s memoir I Can Imagine It For Us, so I thought I would tear through it in one sitting. Instead, it took me over a week to read. Not because it wasn’t gripping, or because it failed to haunt me, but precisely because it did. The book chased me into places of grief, ache, and borrowed yearning that I wasn’t prepared for. I needed time to process. Time to weep. Time to stitch together the parts of myself it undid. You do not read this book and walk away intact, if walking away is even possible. It breaks you open and spills you out.

Serhan tells her story: a Palestinian daughter and her father bound by inheritance, damage, and love forged through exile. The work is deeply personal, but for Palestinians there is no personal; it is all political. Through recollections scattered across continents and decades, the narrative unfolds the way memory does: without chronology, slipping between past, present, and a reimagined family history. This temporal and geographic dislocation mirrors the diaspora it carries. Each scene arrives like a snapshot, then breaks into a shard, catching time mid-fracture.

Serhan braids three narrative threads: the final year of her father’s life, her own childhood and coming of age, and the imagined history of her Palestinian family before the Nakba. The experience of reading is brutal and tender at once, lyrical throughout, and impossible to turn away from.

The title is devastating because it is so intimate: “I have never been to the place where I am from, but I can imagine it for us, Baba, for you and me.” Serhan writes. She must imagine what she can never visit, all the more so because her village, al-Kabri, like so much of pre-1948 Palestine, has been erased from the map. What remains is what is imagined—retrieved from family stories, literature, the accounts of witnesses, and the inherited memory her psyche holds. Remembering becomes an act of survival, a way of writing back what has been erased.

The book’s subtitle, A Palestinian Daughter’s Memoir, deepens this meaning. Serhan is the daughter of a Palestinian man, and also a daughter of Palestine itself. These identities converge in her father, Nizar, who is the heart of the memoir. Nizar is a man whose body carries the geography of Palestinian loss, embodying endured violence, horror, and erasure. To be his daughter is to inherit both his personal pain and a nation’s fracture. That doubling shapes the entire book. The very first line reads: “I am twenty-four when they amputate baba’s foot.” Nizar, a man cut from his land, cut again from his body. The amputation is stark and overwhelmingly symbolic, a metaphor for the collapse of grounding, stability, and safety. A metaphor for Palestine. He loses his foot; he loses his footing. But still, he does not surrender. Defeat is not an option. Every Palestinian has their form of resistance. His body keeps trying to outrun the cut until it can no longer do so, until death claims him in exile, once again severed, this time from family.

Serhan does not write her father as hero or villain. She writes him as a man shaped by a betrayal so deep it never found language. What emerges instead is anger. Frustration. A love that overboiled and scalded. He is a man who slaps hard and weeps in the dark for those he hurt. He hurls insults and then holds shoulders in apology. He drives the women in his life to the edge of endurance without ever wishing to push them over. His anger fills the page, but it is the anger of someone holding a shard of grief that never healed. The grief of severance from identity and home. Shards of a family scattered to the four corners of the earth.

Serhan recognizes damage but chooses to hold it within love. Each time she addresses her deceased father as Baba, she chooses tenderness over distance. The memoir itself becomes an act of love, one that carries compassion without erasing harm.

As the memoir moves across the world— Beirut, Abu Dhabi, Shenzhen, Cairo, Limassol, and remembered Acre, we see a life stretched across maps with nowhere to stand. When the map of home is destroyed, even the map of one’s own family becomes difficult to hold. Nizar rarely speaks of Palestine, and Mai learns nothing of it from him. What he offers instead are fragments: “horse stables and a wine cellar”, is all his daughter gets out of him. She wonders if perhaps there is “…a scream stuck in [his] throat or locked up in a black box.” His silence becomes its own inheritance.

Serhan inherits the diaspora. She inherits her father’s restlessness. She inherits displacement and its aftershocks. She identifies as Palestinian but carries a Lebanese passport and has an Egyptian accent. She absorbs her father’s rage played out on roads and in rooms, the volatility of her parents’ marriage, the violence that spills into daily life. A child who learns early how to hide, who self-soothes in silence.

The narrative shutters click. We are in the celestial abundance of Acre: Nizar, a little boy with two feet, splashing in a spring beside his nanny. The shutter clicks again. A cat is flung across a room in fury. A couple fights. Then another click and the frame changes: laughter returns in a Limassol kitchen, matriarchy gathered close. Another click, another fight, no longer domestic but political, for al-Kabri, for Palestine.

In one of the memoir’s most uplifting yet devastating moments, Serhan discovers her grandfather’s name in Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun. Fares Serhan: the man who fought; al-Kabri: a village that refused to surrender. A family that refused to abandon land or dignity. She reads the line stating that if all Palestinians had fought the way al-Kabri did, the country would not have been lost. The knowledge arrives too late. Her father is already dead. The misalignment is heartbreaking. It lands only in story.

This moment matters because the book is not only about personal restoration. It is about correcting history. Palestine was never a land without people. It was a land of plenty. Of orchards and water. Of flora and fauna. Of education, lineage, and title. A land where, as Serhan writes, “crescents, crosses, and stars moved freely.” Palestinians did not sell their land—they fought for it till death or displacement. As Palestinian families continue to be erased, the refusal of these narratives has never been more urgent.

The memoir’s final movement sharpens this refusal. Unable to locate her village or country within imposed systems of naming, Serhan writes Gaza as her hometown on Facebook. It is an act of defiance. Her village is not a kibbutz. Her town is not Akko. Her country is not Israel. The names offered to her are counterfeit. She dismantles accusation and pity alike by listing the suffering she has never had to endure, not to distance herself from Palestinian tragedy, but to expose how arbitrary freedom can be.

Nizar leaves behind no fortune, despite being a man who built a trading empire, a man who could not tolerate defeat. Instead, he leaves his daughter something more precious: a story. Serhan breathes life into it with love, truth, and dignity, and in doing so gives him a form of return. In the end, though much is lost across borders, dialects, and tongues, it is language, the power of the written word, the power of the story, that remains.

This is why the book is so difficult to read, and why it stays. As an Egyptian who shares borders with Palestine, who share versions of its food, faith, humor, skin, and culture, who shares blood with the book’s half-Egyptian author— but not the half that hurts or bleeds into its pages—I recognize that the trauma is not my own. And the book itself shows why that distinction matters. Trauma cuts deep and is handed down. It can heal with love. For those of us who approach Palestine with reverence and hesitation, witnessing a grief we have not lived, I Can Imagine It For Us offers a way to listen without claiming ownership.

Read an excerpt of I Can Imagine It For Us by Mai Serhan

Acre, pre-1948

Baba, did you ever wonder why al-Kabri smelt like iodine even though the sea was fifteen kilometers away to the west? I’ll tell you why, there was nothing to obstruct the wind’s movement. The mountains and the breeze could both exist. The mountains would fade at sunset and blend in with the colors of the sky, orange and lavender. The water, fifty meters below land, flowed freely from coast to springs, all the way down under the land’s skin, coloring it in bronze and green tones.

It’s all under your skin, I know that too. I know your body parts are the coast, cliffs, valleys and wide plains of your village, and why they too will stop breathing soon. Why you’ll stop running, why your body will break. It will no longer be able to break sugar. You burn a hundred cigarettes a day, Baba; you burn the tobacco fields over the hills every day. But I also know our bloodline, our bloodline is like a tree in a storm, its branches break, they disband in the wind with nothing to obstruct their movement.

I go to China.

I go because where I’m from is not on the map, not anymore, so I seek the edges and overlook the borders. I go because I’ve inherited a gene that roams and the restless foot is mine to bear, too. The ghosts of the past are calling me, asking me to follow in their footsteps, to keep walking out and out. To stop is to know I am out of place, so I move from place to place. Perhaps in the farthest lands I might cease to feel like a stranger. Perhaps in leaving the world as he knows it, my father’s finally found peace, so I follow. Two Palestinian renegades running towards the outpost, thinking we can leave ourselves behind. Thinking we can run until we vanish, with all our ghosts.

Excerpt published with permission from the American University in Cairo Press (AUC Press). All rights reserved.