Karim assured her that the man was certain the address was correct. He didn’t believe their apartment was not advertised for rent, just as he didn’t believe that Mr. Abd El-Hamid, the landlord, had been dead for years. Abd El-Hamid himself was the one who had contacted the broker yesterday and asked him to look for a tenant for the ground floor.

His mother asked him: “Why he had he not called her.” He had hollered for her, but she didn’t answer, and he thought she was busy in the kitchen. He was worried about leaving his room and leaving a stranger standing by an open window, especially this man who was insisting that he should summon her. His mother put her palm on his forehead to make sure that his fever had not gone up again. She advised him to shout as loud as he could, if this man ever came back.

He understood that she wanted to cut the story short—no more questions. She didn’t hear him say a word to anyone when she was close to the room when she came to check on him, and she didn’t notice any head close to the window. He was annoyed that she didn’t believe him. She dealt with his words as if they were merely an extension of his hallucination while ill. She didn’t inform him of everything he was raving about, like the way people act with fever patients. And because they are convinced that everything that had been said should be repeated, he only mentioned a few names of his pals and kept repeating, “Watch out. Be careful,” without knowing the person he was warning. She continued smiling, hoping that was the last thing he said—that she never discovered who it was. He was waving at her to tell all, but she just answered, smiling, “Don’t say it again.”

His mother zipped back from the kitchen, asking him not to tell his father about his conversation with the man. He felt that if he were not recuperating from the fever, she would scream in his face and warn him harshly about mentioning anything. He understood that she didn’t want to give a new opportunity to his father to bring up the issue of placing iron bars on the windows. His mother blocked the notion of these bars, yet she knew that his father wouldn’t drop the subject and he wouldn’t deal with Karim’s story in terms of sheer hallucinations—and it was impossible for the dead landlord to speak. To the contrary, that was more evidence that iron bars are necessary. He would say in his way, “I don’t suppose this did happen, but it could.” He would not hesitate to confirm that this was a new trick to rob houses. The ways of thievery take a thousand and one shapes; indeed, she felt that the comings and goings of life became themselves a form of theft. He would imagine what would have happened had this man accomplished theft. He pictured how he would be able to steal what he wanted in a jiffy, swiftly snatch the television or the fan or whatever his hands could pluck, jumping out of the window, and disappearing before she noticed, and she herself would be still be standing in the room, incredulous, stunned, staring at the spot, that had been emptied of the stolen items. It would be even more catastrophic if she caught the thief red-handed. She wouldn’t be up to the blow and he would suppress her screaming before anyone came to her rescue.

Karim was not bored by listening to his father narrate the details of a theft he had heard of or read about. He was immersed in the story, as if it had happened to him, and he could hardly take a breath between words. The expressions in his face looked as if he were facing the thief—nothing else would do but install the iron bars. While his mother would blame the negligence of those who got robbed, his father would become annoyed, asserting that anyone could neglect their possessions. No one could be alert all the time. He was reminded of the theft of his bag when he was standing at the bank window. And in order not to foment his anger, the mother had stopped reminding him that the bag had nothing in but the newspaper. She quit commenting on his exaggerated stories about robberies. When she told him once that the iron bars would prevent them from climbing into the window if they forgot the keys inside, he answered that he was not comfortable about leaving the flat empty unless they were traveling. His mother replied quietly, saying how rarely they traveled, and he would answer that they also rarely forgot the key inside.

His father used to repeat, “Apparently, there won’t be anybody but us,” when anyone else had bars put on their windows. His mother knew that when any neighbor put iron bars on their windows, he would start to defend them, and would claim the bars would block any danger. To top it off, he always encouraged other hesitant neighbors to do the same, and even directed them to the place from which he bought the iron quite cheaply. When his father repeated what the neighbor said, his mother remained silent, pretending to be engaged with something else. She even quit hinting at the fact that a lot of ground floor apartments had not resorted to iron bars. The numbers had slumped. What annoyed her most was when the neighbors opposite her placed iron bars on their windows, as if they had set up a mirror where she could see reflected on a daily basis what she refused to allow and what his father always desired.

Karim kept peeking out from the window toward the direction where the man walked. His mother advised him to relax on his bed—he had at least another two days until he had fully recuperated and should not get distracted by the story of the man since he would not return. He asked her if she believed him. She gazed at him: “Forget about what you saw.” She reminded him that his father did not deal with these stories easily, as she did. Thank God, he did not listen to everything that Karim raved about during his illness; she was the only one who had heard it all. He tried another time to find out what she had learned from his raving, and she said: “It’s as if I had heard nothing.” It was the first time his mother had gotten mad while discussing his ravings. Before that, her perpetual smile did not reveal that he had let any cats out of the bag. Especially the cigarettes which he had started to smoke and his flirtation with the girls from Giza junior high school and his attempts to hook up with one of them—a number of times he had played truant from school and gone to the Fantasio movie theatre. She could have disclosed a single secret out of the whole kit and caboodle to make him think that she knew the rest. The fact that she kept saying “I didn’t hear anything” made him feel that he hadn’t disclosed any important secret. But he understood how vital it was to avoid telling her what happened in the street or near their window, until he made sure it had nothing to do with iron.

His father returned. Karim was still peeking out toward the street. His mother ordered him to return to bed. Then she came closer and locked the window. His father yelled angrily at her while he was changing his clothes in his room: “Gently. Gently.” He pointed out to her that since the neighbors had placed iron bars on their windows, she had been slamming the shutters, forcefully, as if she wanted to break them. She kept listening to him, the pillow in her hand. Instead of tucking it under Karim’s head, she hurled the pillow at the window and left after she turned out the light.

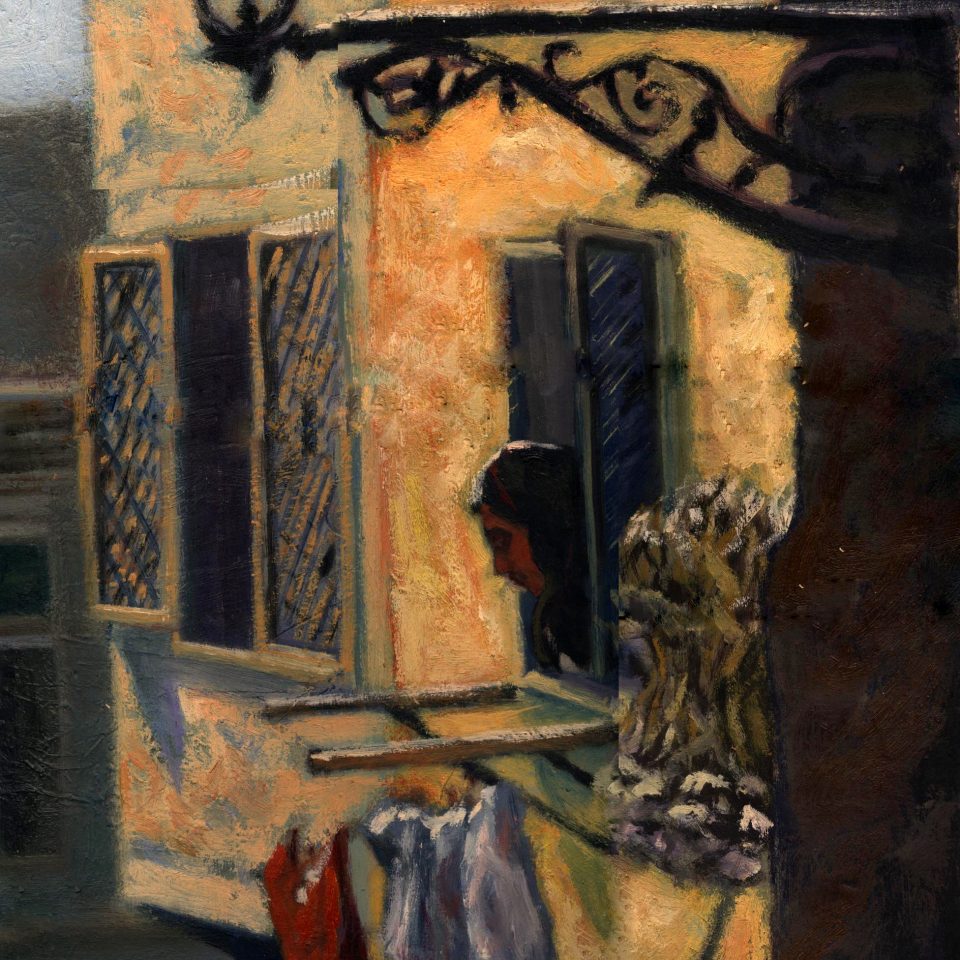

Artwork Courtesy of Reda Khalil

Also by Montasser Al-Qaffash: The Issue of the Light Well