KILMA كلمة, Noun

Meaning: Word, bond, oath, promise

“Rajul kilma” (رجل كلمة): A man of his word

As I approached his armchair, strategically placed in the living room for the best view of the television, I could clearly see the back of his head nodding and shaking sporadically. The rapid jarring movements suggested he might be in the throes of a stroke. However, upon closer inspection, I saw that he was simply trying to end a call on his smartphone, and despite his repeated angry poking and prodding of the screen, the device refused to comply.

When he finally noticed my presence, he handed me the phone in exasperation and directed me to “turn that thing off.” His sister, still on the loudspeaker, could be heard shouting all the way from her balcony in Algiers,

“Badr! Just press the red button—the red button at the bottom!” which I did, with an ease that further raised Dad’s level of frustration by several notches.

It was three o’clock in the afternoon, and he had summoned me earlier in the day, refusing to mention the reason over the phone, meaning a serious discussion was in the cards. Yet, despite the urgent summoning, he began by reporting in detail everything he had been doing that morning and the various annoyances he had encountered. That particular day, he had been doing all kinds of back-breaking work in the garden, and for anyone else, now, would have been the moment when he should have sat down with a cup of tea and rested. But in his case, he sat down and took stock of the day’s various injuries—like head wounds—that he had acquired during his bouts of frenetic gardening. Then he reported the day’s efforts by making a series of telephone calls to relatives or anyone who happened to be nearby, which today included me.

According to his report, the most annoying issue that morning had been a big tree branch he had dragged from one end of the garden to the other. Only after he had gotten the branch off his chest did he move on to the serious business of why I had been summoned.

“I was talking to Majed yesterday, you know, my cousin Majed?”

Majed was one of a multitude of distant relatives whom I had met only once or twice, so his name elicited no more than a blank look from me. My inability to distinguish every person on the boughs of the family tree was a source of great disappointment to Dad, who interpreted my incompetence as disinterest.

Dad waited a few moments, hoping that I would uncharacteristically redeem myself with a sudden recollection of who he was talking about.

“Majed is the cousin who used to be a military pilot… his mother was my uncle’s third wife…”

My blank look persisted.

“He has one leg, for God’s sake!”

I restrained myself from saying that perhaps he should have started with this detail. “Oh, ok, one-legged Majed. And?”

“And, he said he has not received the package yet!”

Dad was, at this point, furious indeed, and most unfortunately, I had nothing to say at all. I could not remember what package he was referring to, or why he was asking me about it.

“You didn’t send it, did you…?”

“Just remind me again, what pack—”

“You didn’t send it! I was sure of it! Just like everything else… I can’t rely on you, ever!”

By now, Dad’s arms were flailing in all directions and engaged in advanced-level Mediterranean gesticulations, conveying a multitude of emotions simultaneously, among them: fury, despair, existential angst, and of course the emotions most commonly evoked when dealing with his firstborn: disappointment, frustration, and, in my view, a misplaced but profound conviction that I had the ability to do anything if I wanted to. It was a sight to behold, and an intervention was required. He knew it, and so did I.

“Linda! Linda!” Dad called out toward the dining room.

“She didn’t bloody send the package to Majed, and I told him we’d sent it weeks ago, so now, now I’m a liar! She has broken my kilma! Majed’s like an old, gossiping woman. He will tell everyone in Algiers! Everyone!” he bellowed with a level of dramatic exasperation worthy at most of a Greek tragedy and at the very least of an Egyptian soap opera.

Even though I still could not recall which package Dad was referring to, I began to understand the gravity of the situation. His “word,” or kilma as it is referred to in Algeria, had been called into question, and, worst of all, amongst his kin. Almost nothing could be worse than this.

“Linda!” Dad called again for my mother—the only person who might be able to guide us through this terrible debacle.

Mum was in the dining room, eating her way through a packet of wine gums. She was usually occupied at this time of day with the internecine conflicts occurring within her current Duolingo league, so it was with some reluctance that she came to see what the fuss was about.

“What haven’t you sent, dear?” she asked me calmly.

My response was a shrug.

Mum popped a wine gum into her mouth, paused for a moment, then addressed Dad, “Are you talking about the trousers?”

“Yes, the trousers!” my dad bellowed back at her as she stood just meters away.

“Calm down, Badr, before you give yourself another nosebleed,” Mum said before turning toward me.

“Your dad’s talking about the trousers with big pockets, the ones he was wearing when he was in Algeria last time. He was sitting outside your uncle’s shop when Majed came along on his crutches and complimented the trousers, saying he’d never seen such big pockets on trousers before. So, your dad promised he would send them to Majed the minute he got back to England, as he wanted to wear them for the journey back, because of how useful the big pockets are for travelling. He asked you to drive 100 miles up to London the next day to send them, because he doesn’t trust the post office here, where we are, it being ‘too provincial.’ I remember you saying you’d sent them yourself and that you had the receipt,” Mum said before returning to the dining room. Having given all the help she could, she no doubt wanted to see how far down she’d fallen in the Duolingo rankings because of this pointless interlude.

Yes, well, now I remembered the “big-pocketed trousers,” known to the rest of the world as “combats” or “parachute trousers.”

Dad had a strange fondness for big pockets. He had only bestowed approval upon three items of clothing over the years, and it was precisely because of their pockets: a jacket from the army surplus store in 1989, an “excellent shirt” in 2012, and the trousers in question, which had only been in his possession for a year. Despite his fondness for those trousers, he could barely think about anything other than sending them to Majed after he returned from Algeria—probably considering that sacrificing them to his cousin was a clear sign of his unquestionable love and loyalty to his kin. Upon his return, he had quickly emptied the trousers of all the items he considered essential provisions for any journey—dates, reading glasses, back-up reading glasses, a roll of cash, tissues, sanitizer, and a small bag of soluble coffee—and put them in the washing machine so that they would be ready to be sent to Majed the next day.

I remembered that my three brothers and I had each tried to avoid being given this particular errand, because none of us wanted to drive to London, until it dawned on me that my friend Valentina would be returning to Argentina for a holiday and would fly out from London—which meant that I would be able to score a few extra points without having to fulfil the mission myself.

Yes, now I remembered the trousers, and my heart sank as I realized that, in a moment of negligence, I had outsourced the whole of our family’s honour to a third party.

“So, did you send the big-pocketed trousers or not? That’s all I want to know now… because I remember you saying at the time, something like, ‘Why does Majed need big pockets on his trousers if he only has one leg…’ and I said to you, ‘He has one leg for God’s sake not no legs, so he can use the pockets on one side, even if he has to pin the other up!’ Even after you told me you’d sent them, I remember thinking, ‘What kind of person would say a thing like that?’ Maybe she did not send the trousers at all because she thought Majed would not use them. If she could think it, maybe she could do it. So now I need to know: did you send them, or did you lie to me?”

And then, to my surprise—and unfortunately as proof of what my mother had always said about me being “exactly like Dad,” with the only difference being that my blood ran a little cooler, but not by much—I felt the sudden burning desire to defend my honour, notwithstanding that in this instance, the accusation was, at least partially, true.

“Dad, this time, you have really crossed the line!” I cried in the voice of someone who had suffered a terrible injustice. “In fact, all possible lines that could be crossed, you have crossed them… After all I’ve done for you, you accused me of this… I dare you to give me one example of me not doing what I promised. Give me one!”

Dad narrowed his eyes, obviously trying to come up with an example, clearly as surprised by my outburst as I was.

As for me, it was obvious there was no going back now, so I decided to double down on my faux mortification and, in doing so, buy myself some time to pinpoint the current location of the trousers.

“I gave you my word, Dad, my kilma, and I honour it no less than you. Majed will get his trousers. I sent them, so they must be on the way,” I finished and dashed out of the house.

A month and a half after the showdown, Majed received the big-pocketed trousers. It did, however, come as a surprise to all but me that the package had arrived in Algeria with a postmark and stamps from Argentina. Dad’s honour had been fully restored, and so had mine as far as I was concerned, so what did it matter how the big-pocketed trousers had arrived at their destination? Surely what counted the most was that they had indeed arrived, just as I had said they would. But the Argentinian stamps had further sown the seeds of doubt in Dad’s mind. Even he could not believe that the Royal Mail was capable of such ineptitude, though I would argue that it was. The physical appearance of the trousers in Algeria made it nearly impossible for him to claim otherwise.

Majed confirmed receipt of the package by sending a photograph of himself standing outside my uncle’s shop, wearing the trousers and giving a thumbs up while my uncle pointed solemnly at the big pockets. This was, I maintained, irrefutable evidence that I had indeed sent the trousers and that my kilma was worth something. I also made sure to explain to Valentina that, if we were to remain friends, she must vow never to tell another living soul that she had ever been in possession of a pair of big-pocketed trousers, and, of course, she must never set foot in my parents’ house.

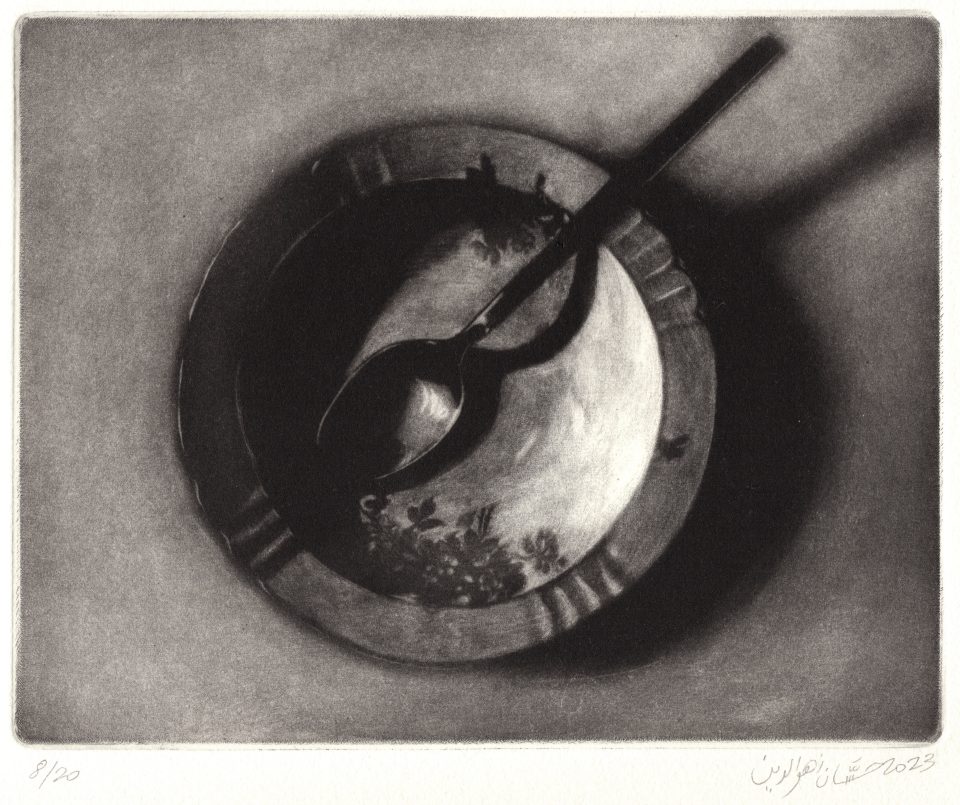

Despite his best efforts over the years to obtain “the truth,” I remained steadfast, much like his smartphone, utterly immune to his repeated prodding and interrogations. Nevertheless, every so often, when I would be visiting my parents, Dad—who during his rare moments of quietude reminded me of the African lions at the zoo: dignified, estranged, and languishing resignedly under the British rain—would turn to me while we drank our coffee and say, “You didn’t send them yourself, did you?”

Artwork courtesy of our featured artist Ernest Williamson III, PhD