Behind the scenes of media and political campaigns vilifying stateless resistance as a kind of inhuman and even animalistic terrorist extremism in the global news cycle, the struggle for Palestinian self-determination is steeped in intellectual solidarity with the popular impetus for just revolutionary action. Its history of ideological sentiment against violent imposition and defense of national sovereignty echoes from Bastille to Port-au-Prince, Leningrad to Ho Chi Minh City.

As the world bears witness to innocent Palestinian civilians exhumed from under the rubble of unceasing militarism between Israel and Hamas, the source of the fighting remains human, as the lines between good and evil blur in the light of day. In such times of mournful chaos beyond mere reason it takes a poet to show how the toughest battles still boil up from within.

Palestinian poet Nasser Abu Srour debuts in English with a haunting exclamation that reverberates with such empathic determination, communing with Franz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth while, in spirit, clutching a copy of Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. And with an abiding talent for poetic phrasing, Srour articulates the cris de coeur of the age:

Our naked, bleeding breasts exposed the lie about a barbarous East that needed the West to refine its primitive savagery. In our lexicon of dignity and worth, the pains of others had no color or smell that distinguished them from our own, for we identified with every speech that rebelled against injustice or supported the not yet triumphant.

Loudly, we rejected tedious panegyrics for kings and sultans. Instead, we read the works of Nâzım Hikmet and Amal Donqol; we read about Võ Nguyên Giáp and Che Guevara. We danced around the fire with the remaining Native Americans. We recited the fatiha over the souls of a million Algerian martyrs. We ran to cut the noose from around Omar al-Mukhtar’s neck in Libya.

In a turn of Levantine romanticism, Srour begins his prison memoir, The Tale of a Wall, not with a call to arms but with a curious, metaphysical quandary. Introspective, indulging in a kind of listless indifference to convey mental freedom despite his overarching captivity, he invokes love as a spiritual ideal via the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard.

By responding to his condition as an incarcerated Palestinian man through a reckoning with basic human experiences, he is disempowering the state of Israel and its abuses of law by relegating the repercussions of its actions to broader, existential questions of being. He opens the first chapter, “Letting Go and Holding Fast,” with the following passage:

Two weeks ago, I emerged from an extended bout of apathy and decided to read a book by Kierkegaard. In the book he talks about love, arguing that the best way to preserve it is to release the beloved and to deny all possessive instincts, such as dependency and egotism. He also claimed that this letting go is only possible through the irrationality of faith.

His literary demonstration of self-expression is that of a man alone with his humanity, pondering the persistent omnipresence of nihilism in the Nietzschean sense of skepticism toward reality as a means to self-determination. His shrewd eye for false definitions runs through his chronicle of childhood remembrances divided by postcolonial territories with unresolved histories of double-edged boundaries, imposed like the place names whose religious connotations ring hollow. On growing up as the fifth child in a family of ten amid suffocating refugee camp housing in Bethlehem, he notes:

I was born in a refugee camp near a place that is still called the City of Peace, even though all Bethlehem has known of peace is its absence. […]

Just when this city settles down to harmonize its breathing to the ringing of bells, the calls to prayer, and hymns being sung, my father turns up, along with a whole caravan of people like him who possess no houses at all. So they erect a tent as their cramped home. Before long, that first tent has become a camp.

Palestinian history is marked by various kinds of defeat. There is the total loss of the Nakbas, meaning catastrophes in Arabic, both during the original sin of pre-state displacement in 1948 and Israel’s land-grab of 1967. The self-sacrificing protests of the intifadas, or rebellions, followed in due course, but as Srour attests, much to the debasement of young Palestinians. As such, Srour distinguishes the Bethlehem refugee camp where he was born according to the materials used by its inhabitants; cloth, brick and concrete, the latter increasingly shadowed by eyesore settlements bathed in sunlight on not-too-distant hills.

Unveiling his wide-ranging, erudite prose, Srour’s voice evokes the existentialist pretext that Jean-Paul Sartre outlined in Being and Nothingness, perhaps best summed up by the quote, “Freedom is what we do with what is done to us.” Or, as Srour writes:

I was like every other Palestinian aware of their bondage, who had to lose their freedom in order to be free, who had to die in order to live.

With the embittered tone of stunted youth, scoured of insincerity, Srour details his trials of imprisonment beginning in 1993, picked up off the streets at age twenty-three as one of the Generation of Stones, alleged to have been an accomplice to his cousin in the murder of an Israeli Shin Bet intelligence officer. But he does not plead against the indictments of his case, even while taking the reader by the hand to witness the horrors of his confession under torture.

The Tale of a Wall exposes the confessional resignation of a man dehumanized not just by Israeli authorities, but before the world. Long having accepted his fate, beyond hope of justice, he resorts to philosophical contemplation, interpreting his confinement through the internalized abstraction of his poetic muses, reminiscing on the greater resistance movement that landed him in solitary enclosures and crowded lockups with the same anguish that he speaks of unrequited love.

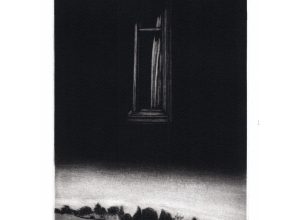

He writes with poignancy of his internment as a microcosm for the universal condition of existence in its sheer bleakness, unmediated by the trappings of experience, his sense of reality lain bare, plain, austere. All that remains between himself and the other, be it death or liberty, is a flat, empty wall. As the writerly metaphor of a blank page, or, as a young rebel realizing the futility of their yearnings, the nondescript surface gives him space enough to breach his sense of collective will toward personal transformation, encountering that impasse of absolute failure which inspires self-transcendence.

Throughout his gripping, nuanced book, peppered with references to classic works of literature and philosophy, Srour grapples with the central theme of deliverance, in part one from the unbearable pain of standing as one among untold, disenfranchised youth born fighting and dying too young to resuscitate the stillborn contractions of Palestinian nationalism, and in the second section, mourning a fleeting, epistolary romance eclipsed by his life sentence.

The first act, stylistic and meditative, reflects the life and mind of the poet, who notwithstanding his national pride in the cause of communal emancipation, assumes the role of the artist, vulnerable to the whims of personal weakness as he conveys his lack of confidence in the ideals of justice and his ultimate desire for self-preservation.

He writes:

Sometimes you kept the faith, and other times you shook off the religious heritage that weighed you down. A freedom fighter one day, and the next day a slave to a reality that allows you to glimpse heaven’s gift, even if its details shatter your existence.

[…] Now you are firmly established within yourself as a self that has been liberated from the religious, social, and political repressions that formerly conferred a sense of protection. […] I had to let go of the possibility of freedom and embrace that wall if I hoped to survive.

Exploring figures of speech inherent in the words “faith,” “religion,” “freedom” and “reality,” Srour’s searching philosophy of despair doubles down on the meaning of conviction, which unravels to contain both a deeply abiding sense of commitment to a cause while being, at the same time, a prisoner, found guilty and sentenced to life in jail, otherwise blacklisted as persona non grata among those who identify as the free and the civilized. But wielding the semiotic rationalism of ethical continental philosophy with an enviable ease, Srour sees the wall itself as the noumenon of Immanuel Kant;

[…] arguing that the reality of things is not outside our perception and sensation. If he fails to convince the wall, he scatters the board and sets the pieces anew, for things are what we want them to be.

The author’s careful elaboration of historic and contemporary agitations for a Palestinian state rests on internal strife as a participant, once-removed, passively observing the rightward drift within the movement’s leadership since the Nakbas of 1948 and 1967, the intifadas of 1987-1993 and 2000-2005, ever mourning the failures of the once-hopeful nationalist camp arguably advanced furthest on the world stage by Yasser Arafat (referenced in his laudatory appeal as a victim of assassination despite lack of such proof in official records).

From inside his many cells, transferred between jails across Israel’s sacrifice zones, he shares the fate of more than 5,000 Palestinian prisoners, musing on the upstart visions of the broader yet more factionalized armed resistance under the banner of Islamism, whose chief arbiters, Hamas, incited the latest war between Israel and Palestine by committing the Oct. 7 massacres that killed some 1200 Israelis before taking 253 hostages, inflaming seven decades of military and economic conflict affecting the civilian population of the Gaza Strip.

Srour’s prefatory nod to the acceptance of faith can be read as the cry of a nationalist Palestinian rebel from Bethlehem in the West Bank, jailed at the bitter end of the first intifada, sympathetic to his greater national community in Gaza, despite the regressive strategies of their token leadership while thoughtfully and creatively contributing to a culturally astute, universally-relevant Palestinian resistance movement as a symbol of righteous indignation against the hubris and belligerence of American-led, Western globalism.

And yet, after nearly thirty years behind bars, the degree of sheer powerlessness that Srour is forced to accept riddles The Tale of a Wall with the underlying plea of the Palestinian passion, that it is not only sovereign nationhood that Palestinians seek, but an opportunity to be treated as fellow human beings in a world that has shrunk, unprecedentedly, from the global village of postcolonial internationalism to the scattered thoughts of each disembodied individual reduced to the incessant buzz of smartphone notifications.

The Tale of a Wall is an echo, fading though it may be, heard by a generation coddled into conspiratorial paranoia by social media newsreels lurid with scenes of genocidal atrocity, if not of Palestine, then Ukraine, Sudan, and elsewhere ad absurdum. Most observers from international civil society around the world exhaust themselves over the tragic realities of Palestinian life. Yet, Srour duly counters the desensitizing, pugnacious influence of mass media with the warmth of his tasteful, deliberate prose, delving into depths of psychological interiority rare in nonfiction.

His grappling with the rage of life-threatening political action is tempered by glowing eruptions of humanist verse. The Tale of a Wall is rich with critical Palestinian poetics, enacting the interplay between social responsibility in the community and the power of poetry to enable a man facing the long march of death in obscurity to survive on dreams. Nourished by sheer grit, Srour finds ample inspiration to write while ensconced by the cold facts of his detention.

The prisoner begins exhibiting the same zeal for the monotony of his day and his possessions that a writer feels for his text. […] In Ashkelon, I would learn to write with small, cramped letters to avoid disturbing my neighbors.

Although he includes all of his comrades in his panegyrics to the martyrs and activists working for Palestinian sovereignty, Srour’s prose poetry often appears exceptionally enlightened for a man bearing such a burden of moral opposition.

Believing in the universality of oppression and the globalization of poverty was all it took to break free of our provincialisms.

We were not yet twenty years old, yet we devoted ourselves to causes that by now had entered their third millennium. We warred against illusions that debased the human self.

In terms of his broad-minded identity as a Palestinian, or more accurately, a human dweller of his embattled homeland, he writes one line at a time:

We were bigger than our country: our sea, our land, and our sky.

We were holier than our holy places: our mosques, our churches, and our shrines.

We were more delicious than our gardens: our apples, our palm trees, and our grapevines.

We were older than our history: Canaan, Adnan, and the Arabic tongue.

A third of the way through The Tale of a Wall, Srour intervenes in his prose with a full chapter written in verse, titled, “In Prison…” He is essentially conveying the experience of being jailed for his readers, as an inward plunge, scraping the bottom of the barrel of his hollowed psyche, expressing his basic will to exist.

in prison…

you are a confession of everything inside you

some of the words you speak

say a little about you, they might convey things

you do not believe

Here, again, Srour is pointing, however subtly, to the forced nature of his confession as a literary device to consider his ambiguity toward faith, both in the national cause, and the religious fundamentalism of an armed struggle that has landed him square against the bald fact of his own mortality, alive just enough to face off with death, one day at a time, submitting to the darkness and silence of his imminent expiration.

in prison…

nothing testifies to your presence

you are not here

you are far from there

a there where nothing still recalls your little details

or misses you

The Tale of a Wall comes at a time when Palestinian nationhood has returned to the forefront of global attention. Prior to October 7, Palestinian defiance against the Occupation had been largely overshadowed by Israel’s protests against Netanyahu’s overhauling the Supreme Court and normalization with Saudi Arabia, as well as the war in Ukraine and other leading headlines. The sense of having been forgotten by the international community is a recurring theme in Palestinian rhetoric and Srour’s memoir of incarceration is a humble rebuttal to that overriding spell of national condemnation to what is largely characterized by voiceless disempowerment.

The second part of The Tale of a Wall, full of melodramatic romance between Srour and Nanna, his lover, communicates the power of being desired and remembered, despite the amnesic, overlapping trends of the mass media that regularly stifles such past offenders by the shadows of obscurity. Nanna, a social justice worker and diaspora Palestinian in Europe, is committed to unearthing him from under reams of legal files, so as to reveal a human face amid one of modernity’s great tragic, political dramas. She stands with him, disputing the notion that Western civilization is a humanist project, suspect in the bloody cradle that raised its founding moral institution in the so-called Holy Land.

Of Nanna, he writes, “born in 1987 in one of the Mediterranean countries across the sea,” younger than him, of Arabic-speaking Palestinian parentage in Italy, much of her identity is largely concealed, but she is his Beatrice, his Penelope. Her story mirrors his on the other side of the territorial borders that define Palestinian belonging on the basis of shared suffering, confronting the mounting transgressions of international law perpetrated by the state of Israel, or as Srour writes, “the Occupying State.”

He reenacts their initial meetings, first as her interview subject then a growing object of infatuation before their chemistry ignites into a full-blown affair, however unconsummated against the cold, unforgiving glass and bars of their conditional visits. Yet, in his words, she is no less ravishing, and worth feeling for. Sensitively, he writes:

There are some faces that surrender the key to their mysteries before finishing their first sentence.

Filled with a desire to write to her, he succumbs to his muse:

I believe…that I am alive though dead, free though a prisoner. I am a young man in his midforties. I am a martyr in my paradise, without any wine or heavenly nymphs.

Again, embodying her ill-fated wish to embrace him, and he takes up her voice, one straining with resistance in its every articulation:

I’ve come to you with a scream: be stubborn.

The most beautiful of sounds is to scream ‘No!’

There is no god but the one dwelling in your face when you see me.

The Tale of a Wall concludes on July 6, 2019 from Hadarim Prison, Cell 33, as Srour declares that he has been born twice and killed the same number of times. First in Bethlehem from Mazyouna, his mother who waits hopefully if futilely for his release, secondly out of the womb of Nanna, and the relationship that blossomed between them.

It is finally, love, whether in the exasperated vein of Kierkegaard or by the comforting breath of his Nanna, that distills his faith in the future of the Palestinian national ideal into the hard truths of the life he lives, undefeated if only because he remains proud of being human, affirming his existence one word at a time, whether in poetry or prose, his is a voice muffled by his enclosure yet ringing clear, transforming the emptiness of a wall into the fulfillment of his tale; this evocative, wise book.

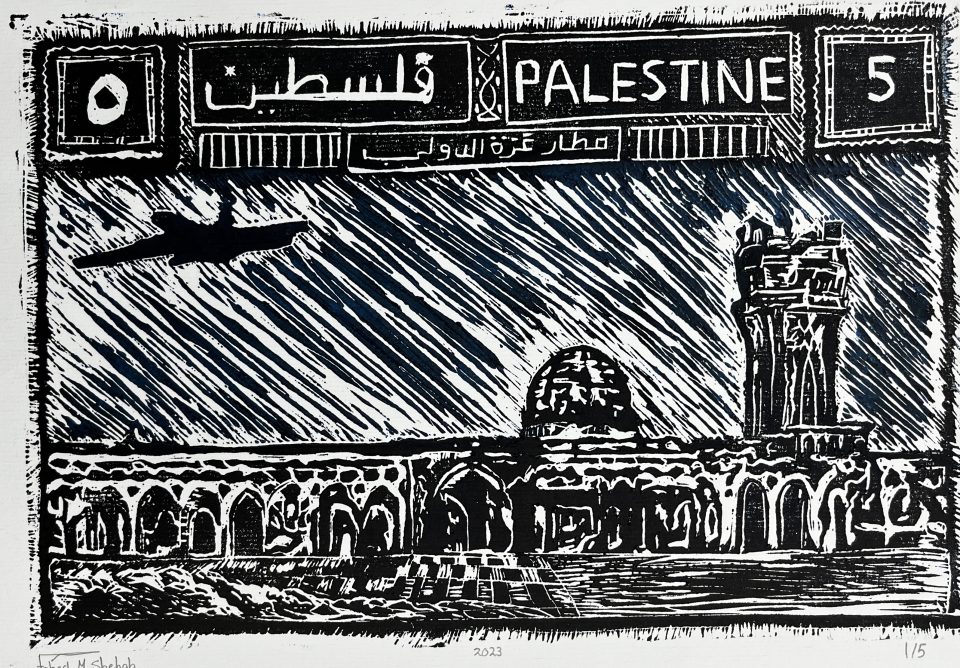

Painting Courtesy of Our Featured Artist Fahed Mohammed Shehab