I

Whenever I think of my mother we are on a beach – even though we didn’t live by the sea. And whenever I think of her I think of the colour gold, even though she hardly owned any gold jewellery, only a pair of hooped earrings like two snakes intertwined.

It seems to me now that she had always been liquid.

Hairspray particles on a mirror. Bronze perfume in a bottle. She was always already leaving. She was always changing shape.

I can see her standing on the shore, watching the stranger take me into the water. The cliffs, the crags, the rock pools. We had been collecting bright crabs in a bucket. We’d put them back after. For now they crawled confusedly, bright red in salt water.

I can teach her! said the woman, when my mother said, My daughter can’t swim yet.

I can teach you too!

My mother said No thanks, laughed. She was fine…

She stood in the bikini I remember distinctly because, like all of her clothes, it stands out now where she fades. I can feel the pink towelling of her bandeau top, the warmth of her skin. Her hair was gold and her heart so big and red that it coloured her whole chest pink. She was home and she was death, because one day, she would be gone. I tried to guess when it would happen. I asked all the time, as I got older: Is anything wrong? Do you have any pain? Is there anything you’re not telling me?

She always laughed.

The woman who taught me to swim, I remember, was like my mother and yet nothing like her. She was blonde and sunburnt, and she had big, white teeth. I knew she was stronger than my mother physically. And I sensed somehow, even then, that she was less vulnerable to death.

Now, incredibly, my mother was nowhere. Nowhere. But even when she had been there, the scene had always been filled with the quiet threat of when she wouldn’t be.

My mother and her sisters all looked alike. They had the same laugh, the same voice, and laughed at things when they were together that I learnt to laugh at too. Look at her, they’d say, Isn’t she like her father? My father I didn’t know. Still, my mother and I were like one, like water poured into separate glasses that seemed to have taken on permanent shapes.

The two of us, always just the two of us.

As I went out into the sea with the stranger that day a thick sea fog fell. It swallowed the beach. My head bobbed, my armbands bright. I could hear my mother calling from the shore. The stranger kept the low rolling waves from my face, her back to the horizon. The black water, her big, white teeth. She placed a hand under my stomach, and showed me the movement. Then she swam back a bit and held her arms outstretched. I swam to her in a few, frantic strokes.

That’s it!

Good!

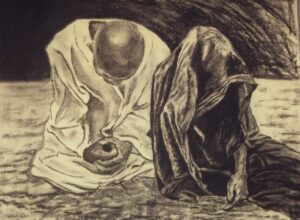

And when I reached her I clung onto her and she said, Do you want to stay on this island with me forever? I must’ve said no, and that must’ve annoyed her, because then she did something I’ve never been able to forget. She grabbed my head and she held it under water. I can still feel her clawed hand, still feel the inside of my head flushing with salt. It could only have been seconds, one, two, three, and I’m not sure what distressed me most, the shock of what she did or what she said before she did it. People we love always leave us. They die, or they swim away. Don’t ever forget that.

She swam back fast, holding onto me, to where I could feel the stones under my feet. She pulled me, hard, onto the beach, where my mother slowly came into view. The rocks of the cove were invisible, and as we climbed back up towards the hotel only the pine needles poked through the fog. My mother apologised that I’d got myself into such a state. She gets it from me, she said. I’m scared of the sea, I know, I know, it’s pathetic… But the woman didn’t reply. She had gone, disappeared into the squid grey air. We took one step at a time up to the road. I was trying to catch my breath. Short, sharp inhalations, my head still full of saltwater, my eyes stinging. I didn’t tell her what she’d done, the sea woman, what she’d said. If I’d said it outloud, it would have come true: People we love leave us. They die. I already knew even at four or five that you had to be careful with your thoughts.

I’d never known what to do with premonitions. I knew there was a relationship between my thoughts and what happened, but couldn’t understand it. I did everything to avoid thinking, just in case. But it wasn’t what you thought deliberately that happened. It was the thoughts that happened to you, the ones you had when you were on the verge of not thinking at all, half-thoughts that took place somewhere at the back of your mind, like a dream.

We didn’t see the woman again after that. Not in any of the few restaurants that lined the rocky coastline, or on any of the beaches in that port town on the quiet island of Ogygia, which, in early-September, was all but emptied of tourists. There were handmade jewellery shops that sold red coral and sea sponges and shells that were tigery and pink. She wasn’t in those or by the port where we drank Coke from glass bottles, or in the labyrinthine streets where old ladies in black sat on steps in silence. I went around frightened everywhere we went after, in the jelly shoes and a T-shirt my mother had cut the bottom of into long, thin white strips that curled in the afternoon heat.

We left the island a few days later, on a big square boat. I remember watching the white port disappearing, the tinkling masts and sails of fishing boats, and I thought I saw her, the sea woman, standing on a piece of dark rock that stuck out of the water like a tooth.

The sea was everywhere, and the boat turned it over, turned the diamond blue sheet into a big, white beard as it went. I hung my head over the back and pictured something chasing us as the water was sucked down and thrown up by the engine.

After that it seemed as if my mother and I didn’t exist together in time. I was more intensely aware of her mortality, and so it was almost as if she were always already dead. The fear never went away. You are always a child with your mother, even when you are like sisters, even when she becomes your daughter.

The idea of Greece became like a haunting — all the islands, their stories and the sea, the sea that went on and on, boundless, and could kill you. It was something I could never get out of my head. Very early on I knew what I was going to study, not just because it came to fascinate me, but because I feared not understanding it. I felt like knowing the myths would somehow save my life one day.

What are you going to do with it? my mother asked later, about the Classics degree, In the future? I remember her taking a cigarette from a packet and lighting it, crossing her legs in high-gloss gossamers. She hadn’t been to university, and had gone back to work when I was four weeks old, she’d had no choice. Tell me again, she said, before I had a chance to answer, What is it, exactly, you’re studying?

When we came back from Greece, the smell of her was different. She had a briny smell, silvery-wet like plankton. It was the cold smell of rock salt, sometimes the bitter smell of seaweed. It was a green smell. The smell of life concentrated and of disappearance, of lost sailors and approaching pirates and time and change and dissolution.

II

I was thinking about all of this, walking along in last night’s clothes.

My mother had been dead a whole year. And there I was, wearing her coat, looking faintly like her in all of the ways that didn’t matter anymore.

After her death I was just trying to survive, minute by minute. Apart from an intense programme of therapy, I read and did everything I could think of to understand it.

I read the Bhagavad Gita. I read Lao Tzu. I read Rumi and Krishnamurti and Jung and Raja Rao, Salinger and C. S. Lewis, T. S. Eliot. I learnt mantras in Sanskrit, Persian, Punjabi, Hebrew. I said the Jesus Prayer. I tried three types of church. I went to The Theosophical Society. The Dhyana Centre. The Buddhist Society. The Kagyu Samye Dzong. The School of Psychic Studies. The Kabbalah Society. Decided I was dying a few times, decided I didn’t mind. I still missed her so much I couldn’t breathe, and still it made no sense. Trying to make sense of her being gone was like trying to conceive of all of outer space. I felt like I was dead myself, like a no one, an ellipsis, a negation.

Mum. What a small word.

Now that she was gone, I only knew what I wasn’t. I had never known where she had ended and I’d begun. She had been torn from me, and now, in the half that was missing, something was growing, something without beginning or end, something dark and wet that seemed to know things I couldn’t yet know myself. She had been the only definite part of me, the first part. And yet I worried now, for no real reason, that I hadn’t ever really known her, just thought I had.

I’d see her just as I was waking up, still in a half-sleep. Things I’d forgotten would be crystal clear: the exact feeling of being near her, the cornflower blue of her eyes, her glittering laugh. It was as if I absorbed her through a single, sharp sense, the way an oyster might; as if she were a liquid taken from a spoon, a taste, a perfect memory, a kind of wonder.

Almost every night I took one of the very strong sleeping pills and flicked again through a few of my old books from university I’d found at home in boxes. The Hellenic World, The Greek Myths, The Odyssey and an unreturned library copy of The Metamorphoses with thousands of notes in the margins in different writing. There was also a book of Sappho with torn edges.

It was another dark summer’s day. The summer seemed not to have come at all that year. Or to have only appeared like a long, stretching shadow.

The Clerkenwell Road was like the City on Sundays. Dead. The only life spilt out of the church of San Pietro, from the late morning mass. The building had a fresco above the doors that depicted the Miracle of the Fishes in blues and golds.

Three little girls were standing on the church steps, their hair like mermaids’. Their dresses swooshed as they twisted at the waist, which they did coyly as they spoke. Pink and white dresses. They looked like little cakes piped with icing. Grey clouds gathered above their heads.

There were three older girls, too, standing in sullen conversation. They wore all black like their mothers. Fifteen? Seventeen? They were like pieces of myth still. Long horse hair down to their waists, bones in their chests, their ankles, like fishes’, swelling out.

I thought I could tell which ones their mothers were by the way they looked panickedly or proudly across at the daughters who ignored them. They lifted their princess hair from their chests, the weight of it, and dropped it behind them, as if it, like their mothers, had nothing to do with them. Everything was unbearable in their world. Everything touched each already too full moment and threatened to make it overflow. One of them felt an urge to capture summer, or was it her own beauty?, and put it in her pocket. What would it be? A large, frightening shell?

It was as if they had stolen something from me, those girls, with their shimmering skins and their mothers, and their delicate, delicate bones…

The rain came and smelt of silver.

The little girls floated under the portico like bubbles. The older ones ignored the rain, as if it were just another symptom of their existence. Their mothers fussed around them, putting up big, black umbrellas that were annoyingly convenient.

And then – they turned to liquid, all of them, the mothers and teenage daughters, they all turned to liquid, and fell fast out of shape. They fell into the gutters and swirled like squid ink down a single dark drain.

They were like the Oceanids, I thought, putting my hands in my coat pockets and walking away. Daughters of Titans. Three thousand. They were like all the multiple Classical women: the Seasons, the Hours, the Fates. The mother goddesses conflated with their daughters, their sisters, each with her own multiple names.

Three girls. Three mothers. Two large clouds – one, two.

How nice to blur, to blur with others, and never be alone.

*

My grandmother said that she was going to call my mother Faith, but something made her change her mind. At the last minute she gave her a name that meant ‘Bitterness’ or ‘Star of the Sea’.

The only faith I had was in darkness, faith that if I kept walking into it I would find her.

III

Maybe it was because my mother smelt of the sea that now she is gone I go after men who are like pirates. Men who are unknowable, men who come and go.

I like the repetition of loss, its certainty – the fear or the fantasy of never being whole.

I walked back towards Bloomsbury listening to the rain, letting it seep through my clothes, feeling my hair stuck to my face like tentacles.

The smell of him, the man from the night before, was dense and sharp and filled my whole skull. Amaro was the same as death. And what else was he? The sky had been a fierce blue flame when I’d left him. It had gone on and on like the sea and looked like it could kill you.

We had been close. We had been so close. We were still one and would be for hours.

I could keep us being one if I imagined it enough.

Bittersweet impossible Amaro.

We met up at Bethnal Green. My new, second-hand dress was black velvet and studded with tiny silver stars. He sauntered up to me, like old times. He always wore the same heavy black boots even in summer. I could barely hear him when he spoke, his voice was lazy, a low, gritty stream. He had an accidental beauty like sheer rock that always stunned me. Looking at his face was like looking at the face of a man for the first time.

He asked whether I’d be willing to fuck right here, and pointed to the public toilets, and when I said no, no way, he held my face in both hands and kissed me for an hour.

His tongue was fat, and the moths were fat under the streetlamp’s yellow light.

We walked back along the long, dead road without touching.

He was unromantic except when he talked about glamour and revolution, which he did sometimes, as if recounting a dream. I could see his moustache, his dark eyes and hair on a poster, his heavy brow, his reckless spirit I romanticised (by way of projection) as a willingness to die.

He had once told me he had no ego, and I remembered thinking that that was impossible. I’d always sensed he’d imagined existing for a higher purpose than just himself somehow. Now he worked late at the Marriott, wore a uniform, lived in a flat with seven strangers where techno came through the paper walls till dawn. Don’t you miss it? I asked him, You know, home, the woods, the beaches? What about your mother? He didn’t answer. We smoked and listened to the Stones.

There had been no moon. He had taken all his clothes off himself, first, like a child. He had grown twice as fat. There was twice as much of his rough love. Twice as much of his mouth, which he kept wide open. Twice as much of his tongue – he was starving, and I felt as if I wasn’t even there.

I watched myself in the caramel light of the mirror, watched him hover over me, his body like a small god’s, his thin legs and chubby top half, the tiny pair of fluttering wings. The wings were beating so fast I almost couldn’t see them moving. The effect was more like a noise, a sort of blurring in the air. I tried to not look at them in motion. They always made me feel nauseous, maybe because Amaro acted like they weren’t there. It was as if they had shifted into irrelevance in the cruel city, in the half-life he was living.

Afterwards, he lay on his back, and squashed the wings into the mattress.

In the night he rolled over, away from me, as I lay wide awake. I put on a lamp by the bed and looked at the wings. They were the same colour as his skin where they joined his spine. But the feathers were mostly a creamy blue, and in some places they were like mud, and in others like ice, translucent. Something about his body beside me, rising and falling, made me feel sad, and I couldn’t tell whose sadness it was, mine or his, or whether it had always been both.

I turned off the lamp.

I knew I wouldn’t see him afterwards for months, maybe never. It’d always been that way. Amaro drew a definite line between himself and all permanence.

I felt like I loved him. I knew it wasn’t love but there wasn’t a word for this, something like love highly concentrated, something primordial, more like a madness I had felt for thousands of years.

It occurred to me, as I lay there and he slept, that we were similar, that our greatest fear bounced off each other like sunlight off mirrors, and in our own opposing ways we both seemed to say: Leave me alone. Both seemed to know that it was better to guarantee the pain of isolation than risk the possibility of happiness.

I left as he half-slept. He made a gruff sound, a goodbye, from beneath the sheets. By the door, on a mirror, was a Post It note he’d written an affirmation on to himself that said:

This darkness won’t last forever.

I wondered, as I disappeared down the hall, quick, so I didn’t see the big, black communal dog, whether I could save him from his darkness, or whether I was a part of it, a part of his dark descent, just like he was a part of mine.

The next day I replayed the night over and over, walking through the rain, treading through the black water of what was once mothers and daughters, jumping in puddles – in their black liquid church clothes, in their love.

The pain of separation from Amaro would come later. But I could almost feel it by memory, the abstract need for the other. Everything had been arranged to make the fleeting oneness possible, and now the night was over and would never return in the same way. Amaro had been swallowed into it, sinking with a feeling of rapturous escape no doubt, into the peaceful, purest black.

The day was wet and it was getting darker. I walked into it, with my eyes closed, dissolving.