Everyone knows about the 1957 launch of a dog into space, but few know about the cats who tried to retrieve her. The clowder of strays staging this operation were not friends to dogs. In fact, the news of a dog being blasted into hellscapes unknown came as a welcome subject of jeering for the cats. Immediately after hearing this on November 3rd, Jura, the leader of the strays, went out to find a dog to heckle, “Days of ‘Man’s best friend’ are done, you pooches. Bipeds are going to rid the planet of you. Bit fucking late, if I’m an astrologer. I’d have punted the first of you right back into God’s balls. You’re lucky nobody lets me make these decisions.”

Of course, Jura made all the decisions for the feral colony, but she felt somehow oppressed by the fact that she didn’t make all of the decisions about everything. She had heard that rulers must rule with the consent of the governed. She somehow interpreted that to mean she personally had to be consulted and consent to all decisions conceived in the cosmos. She developed a real victim complex by how things more powerful than her seemed to act without her input. This was due, largely, to the fact that she was a cat, a species which famously struggles with the condition of also being just a cat. Of course, as a ruler of her peers, Jura was a fierce tyrant and allowed herself some delusions of god-king status. There was a character in The Old Mewings named Tropo whom Jura would think of and say “Why couldn’t that be me? The description of Tropo seems to describe me pretty well. What an amazing life that would be, to be thought of like a character in an old story.” While she couldn’t come up with an argument against her own divinity, she equally was unable to disprove that this was entirely a lie she told herself to avoid the reality of being a low-class creature with no cosmic significance.

One time, Jura was telling a mewing about the before times when cats ruled North America with ruthless domination and dogs were pushed to the point of extinction. There was a slight anachronism in the story that Pedantico pointed out. Jura clawed his face. Out of spite, Pedantico falsely accused Jura of an even greater anachronism where she had used “cats” and “dogs,” instead of the ancient feline and canine counterparts. Jura clawed deep into his throat and pushed the gasping, pleading cat into traffic. This was the particular way with this clowder of cats, they ruled by assassination. If a ruler didn’t assassinate, they’d risk looking ready to be assassinated.

In the instance of Jura, this undoing started by making jokes about Laika to a dog on the third day of November in 1957. Jura was up a tree in a literal sense. It was the only way to avoid being disassembled by the mutt she was mocking. Jura hated heights. While she didn’t mind climbing, she avoided it due to a lack of skill regarding getting down. However, at the moment, she was appearing to do well by disguising her fear with overt hostility. As a leader, she had learned to always act as though there was an audience, where every interaction was a scene she must win. When the scene is about whether you should live or die, there is enough importance to merit getting rough.

“Go fetch some fucking self-respect, you Nazi trash fucker.” While cats didn’t understand world wars, they did get the concept of genocide and adopted the human word, “Nazi.”

The dog, Bruno, barked some nonsense, “Cat, your tone is not appropriate. While yes, I will defend myself at you until you are dead for your words about Laika, you’d think that you’d at least face death with some class. And while some dogs feel the only good cat is a dead cat, I assure you I am a moderate. I think that there are some good cats as long as they domesticate and learn to speak properly. While I am no fan of socialist dogs, I feel deeply for the plight of Laika. Similarly, I am no fan of American cats, but I am sympathetic to the plight of the occasional articulate stray feline. However, if you’re going to keep being so unkind to me, then I might change my political perspective and see you hang from that tree.”

Jura rolled her eyes. She hated when racists tried to mail hate in a compassion envelope. When she killed someone she did it out of violence and because she was mean and godly. She didn’t understand the need to pretend it was some selfless, altruistic deed. Because of that she felt herself to be the moral better of killers who need to sell themselves on what they do.

Bruno rambled on, “I hope you understand that I believe all lives matter, and I try very hard to think that includes cats as well.”

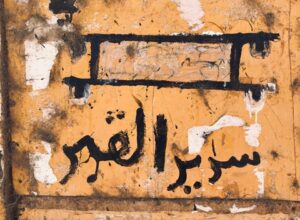

“Don’t strain yourself under such a burden on my behalf. It’s not good for you to have such an enlarged heart and all.” The rhetorical form Jura was best at was something similar to the sharp, demoralizing mockery called Hijā,’ poetry used by Arab tribes throughout the Middle East to rattle their opponents before battle.

Meanwhile dogs had the rhetorical style of a human who learned fallacies in 11th grade, but not actually, and then never questioned their own beliefs with said fallacies. “Ma’am, that is a strawman argument! You have misunderstood my meaning, and your attack misrepresents my goodness. You frame it as something bad because you’re cynical. What you said is a strawman!”

“Your mother was bred to be a serotonin addict and a dumb bitch!”

“And that is an ad dog-inem!” the dog barked.

Jura decided to code switch to mock the canine’s lofty diction, “You’re unskilled at being a canine and morally malaligned. In multiple ways you’re a bad dog.”

Bruno took a lunge at the tree, sliding as the bark gave way under his weight. “I will end your life as a favor to cat-kind! Keep your dirty ideas from other strays who might find the joys of domestication! I will gnaw on your femur! I will lick your pelvis clean!”

“Don’t threaten me with a good time,” Jura said with a wink.

Laughter came from cats hidden all around. There is always an audience. There is no winning the argument, just winning the crowd.

“You will be dead! It will not be a good time!” the dog shouted.

Jura saw Bruno was tangled in the leash of conversation and decided to give his collar a tug. It isn’t enough to win a debate about whether one lives or dies with a logos argument. If the opponent can walk away with dignity and strength, you are in a crisis. They need to be clowned so no one identifies with them or what they might say. “Well, sometimes when I mated, I wished I was dead, so you’re not offering me the worst of it, are you?”

The cats meowed in laughter. The crowd belonged to Jura.

Bruno shouted, “You’re so dumb you don’t realize I’m going to murder you!”

“Can I be of some help here, Bruno?” a cat asked. His name was Helico, a reputed coward who was prone to uncowardly deeds, but in ways that maintained his reputation regardless. He was a tuxedo cat whose natural patterns resembled that of a human dress suit, which is rumored to be why dogs awarded him a level of respect. He knew how to code switch and so some of the less fascist dogs would allow him an audience. Helico had the build of a female cat and when other creatures referred to him as a she, he did not protest the way most male cats would. His name means “Sprial” or from a cat perspective “One who is difficult to label or understand, one of indistinguishable direction.” Spiral is also a slur for cats, meaning someone who seems to exist outside of social definition and norms.

Helico feigned listening to the dog’s complaint and dismissed him with a simple “That sounds like a stressful time for you. It seems like you’ve done enough here. Let me handle things.”

“You’re right, Helico. You’re one of the good ones,” Bruno said.

Helico gave a half-smile and wagged his tail.

The dog misinterpreted the tail wag as happiness and felt proud of his open-minded ability to bridge the gap between species. So he started for home feeling quite good about himself.

Jura, however, could not leave it at that. As her cats watched the spectacle from their safe spotting points, Jura managed to pick out the faces of a few opportunists, like Dyna who had been itching for an excuse to kill her and rule. While Jura was not bad in a fight by virtue of fighting dirty, she lived by the philosophy of the fight avoided was the fight won, at least when your opponent was certain to kill her. Dyna was particularly terrifying and couldn’t be avoided by climbing a tree. Jura could imagine talking points in Dyna’s speech about how Jura was so mighty yet needed to be saved by a spiral. It’s less dangerous to fall from a tree than to slip in respect. Jura couldn’t leave the appearance of power in the paws of the scene-stealing Helico. She shouted, “Yeah, pet, get home to your television programs. Watch that bitch-whore Lassie.”

The cat crowd meowed in laughter.

The dog paused.

“Don’t trouble yourself over it! She’s just a cat,” Helico shouted, and the dog left.

“Just a cat? What does that make you, your majesty? A puppy? No? A skunk then?”

A-Cat-Whose-Name-and-Significance-No-One-Remembers is thought to have shouted, “He looks like the cat the cartoon skunk is in love with!”

Chuckling, the colony seemed to forget that their unpopular leader was up a tree and not likely to know how to get down. So with a simple redirect of their scorn, the colony lost their chance at an easy coup attempt. Assuming the scene was over, one by one, the spectators returned to that which better occupies a stray cat’s attention, naps and sunbeams.

When the last cat had gone, Helico climbed up the tree, joining Jura on a limb. The branch wobbled under his added weight, and Jura shamelessly plunged her claws into bark like knives into Caesar, a regretful revelation of fear. She scanned Helico for murderous intent, but couldn’t find any. Did that mean she was safe, or was Helico just a cold murderer? Jura had seen it in other cats that had come for her life, and secretly hoped other cats saw it in her. As far as feline tolerance had come by 1957, there was just no understanding who or what Helico seemed to be. He negotiated with dogs. What else was he capable of? Speech with bipeds? Helico had an undeniable power and so she had kept a rule to avoid him. Now she had called him a skunk to maintain the tentative favor of a few ignorant dumpster cats.

In the old mewings, there are stories of sacred beasts capable of bridging worlds. Dogs answered to Helico, so what kind of divine wrath did he have? He seemed on the side of the dog. Why did he wait until there were no witnesses for what he was doing now? Jura knew it was stupid to take the old stories to heart, but she had a fool’s heart, and that heart was anticipating holy judgment.

She justified her tyrannical cruelty as the actions of a sweet-natured kitten who refused to let a mean world beat her. She wondered how much weight these words would carry before a god. In the old mewings, there are stories that tell of two reactions of a fool who is not right with their god. The first is to bow and beg for forgiveness, gambling on a coin-flip judgment. The other is to harden one’s heart and see what happens. Jura didn’t spend any of her lives being someone’s chump. “Helico, how do you fucking stand yourself? Talking to dogs like that? Seeing a male like you makes a girl want to get spayed.”

Helico pretended to need to lick his paw, then his face, a self-soothing behavior that looked a lot like coy apathy. “You believed that act? Dogs just want to hear that they’re good and not racist. Just tell them what they want to hear and they will let you exist in their territory.”

“Just because they piss all over it, doesn’t make this land theirs.”

“I’m just trying to tell you how to survive.”

“I don’t survive like that.”

“You must be tired from always being so strong,” Helico said, “You’re very high up. Can I show you how to get down?”

“I don’t want to fall,” Jura admitted, her claws digging deeper into the branch.

“You’re not going to fall,” Helico assured her, “But sometimes going back to where you started is the worst fate of all.”

Helico’s plan was a matter of unique perspective. He told her to just run down face first, then treat the floor like it’s a wall and climb up. Instead of climbing up the “wall” she’d be running normally on the grass below, burning off her excess momentum.

Jura rolled in laughter from the safety of the ground. The plan to “climb up the floor” was stupid-in-brilliance. Jura thanked Helico and asked, “Why did you help me? I wasn’t exactly ever nice to you. I think at best I tried not to think about you.”

“‘Tried?’ You put effort into not thinking about me?” Helico asked.

“You should be glad I do,” Jura said, giving Helico a brutal glare. She was joking, flirting even, but only managed to be absolutely terrifying.

Helico glanced away and redirected the conversation, “To answer your question. I just don’t believe in a world where someone can get stuck up a tree and no one helps them down.”

“Yeah, that’s a pretty hard world, but it’s the place we live, isn’t it?” It felt deeper than just being in a tree. Jura somehow remembered being very small and under a dumpster knowing that mom was not coming home anymore.

A part of Jura wanted to relax for once with another cat. That part thought that if a cat existed that she could bond with, it would be this frail boy. Then she remembered Helico ate food from bowls set out by humans and was above hunting. A collarless outdoor cat is not the same as a stray.

Helico asked, “By the way, what did you say to that dog to get him so mad?”

Jura smiled, not even trying to contain her delight. She explained the situation of Laika in space with poisoned food that would euthanize her in a few weeks.

“Is anyone trying to save her?” Helico asked with pathetic sadness in his eyes.

This was why Jura tried to not think of Helico. He had a feminine beauty and a lightness to his emotions that felt like definitive proof that no god would ever be her, when they were so clearly him.

A human saw the two cats together and said the human word “meow,” which in human means, “meow.” But the feline language is a tonal one, and the human happened to hit the inflections that made “meow” mean, “Hello, my friend Helico.”

Helico replied with confusion, “Hey, how’s it going?”

Seeing Helico had a human friend he could talk to, Jura had confirmation of what she had always feared was true, a greater divinity outside of herself. Her own destiny reduced to being the sainted witness to someone else’s miracles. Seeing the light of the rising moon bringing a glow to Helico’s whiskers, Jura was powerless against the illumination of new purpose.

On November 4th at noon, Jura had the colony gather behind a parking lot that was a key landmark of their territory. Before Helico could speak, some of the strays started to leave but were shepherded back by one of Jura’s threats, sending a message of what was expected of the rest of the crowd.

Helico explained that they were going to launch “Project Dogcatcher,” the most ambitious infrastructure project of all feline kind since Breva dug under the fence by The Wide Mouse Field. This grabbed the attention of the cats who regularly enjoyed the quality of life improvement that the shortcut tunnel had made. The hunting in The Wide Mouse Field was tough, and a last resort for a food deprived cat, but walking around the block just to start a desperate hunt was not the best use of calories. The tunnel was a significant improvement to the clowder’s culture.

“So if we help you, what do we get? The world doesn’t need another dog in it,” a cat named Porto asked, “I helped Breva dig because I knew there’s hunting in The Wide Mouse Field. Is there hunting where this Laika dog is?”

“Um…” Helico had assumed when Jura gathered the colony that she had already done the convincing. He didn’t realize he was going to be up there making a pitch. “There is no real return on investment beyond living in a world knowing no creature gets left up a tree, literal or figurative.”

The colony wordlessly shifted their gaze from Helico to Jura, piecing together how their ruler was up a tree, probably saved by Helico, and now Helico was telling them what they would do for the next several days.

“Why should we?” Breva asked.

“Look, we either get the dog down or it dies,” Jura shouted, “You can’t waste away half a dozen of your lives eating trash and sucking in sunbeams then complain about giving a few fuckin’ days.”

“Yeah, but those are our fuckin’ days! You can’t take them from us for no fuckin’ reason,” Breva said.

“I guess I can’t,” Helico admitted.

“Helico is Tropo!” Jura shouted, “From the old mewings!”

There was silence. Helico had the same terrorized look in his eyes as if it was the human fireworks day that happens in July. “What in every fuck, Jura?” he whispered so the crowd couldn’t hear. Helico wanted to manage expectations, but the myth of Tropo could not allow for anything short of a graceful success.

Once upon a time, there were two deities, one of sky and one of Earth. The one of sky had to jump to stay on the ground, and could only stay for a few seconds before falling upwards. The one of Earth could not jump at all. Tired of meeting only in moments, they decided to be incarnated as animals. The problem was, they could never remember whether they were going to be dogs or cats in the next life. Each time one would be a dog, the other would be a cat. Eventually, they decided to spin both of their spirits into one creature, becoming the plural, transcendental deity called Tropo. This creature would have mastery over feminine and masculine, of up and down, of cat and dog. They would find only theoretical boundaries, semantic boundaries, but nothing could be truly an obstacle.

Jura had once played this hand of Tropo standing before them, using her own masculinity and canine-like fierceness to justify her divine rule over the cats. She had also played this con to get a hotly contested, discarded meatball from Dyna. It seemed playing this hand now would push her already strained credibility. The sideway glances and dared back talk were dangerous reminders of how fast and loose Jura had been playing her leadership. Maybe that’s why she was allowing Helico an audience with her colony; she had been wasting her powers on things like scraps of trash from an Italian restaurant dumpster. If someone was going to kill her and take her throne, she wanted the whole thing to be worth something.

For now, this is what she allowed herself to believe; this was simply a gambit. If her power was going to evanesce anyway, then she was going to wreck it herself. What she truly believed was that she saw Tropo in Helico, and she had batted her future into the paws of her colony in an odd moment of sincerity. She had believed something so absurd, her own mind came up with a sensible lie to cope with it.

“I see it,” Breva said, “He’s a fuckin’ spiral.”

“What’s wrong with being a spiral?” Lumi The Spiral demanded.

“I’m saying he’s hard to understand,” Breva said.

“Like the paradoxes of God?” Lumi asked.

“Yes!” Jura jumped in, seeing an ember in need of air. “I’m not just saying Helico is holy, I’m saying he is specifically Tropo, and this fucking task is about closing the gap between Earth and sky! Do you all understand what this means for us?!”

“Being a fuckin’ spiral doesn’t mean he’s holy. It means he’s fuckin’ weird,” Porto vetoed.

“Being holy is fuckin’ weird or it’d be normal.” Lumi argued.

Helico had completely dissociated. It was enough for someone to call you a deity for political purposes, but another thing for people to start to believe it. Then Jura said something that snapped Helico out of his daze and showed him this wasn’t just a ploy to sway the masses, “We all know he talks to dogs, but I saw Helico talk to a human. The human knew his name!”

“Come on!” Breva asked, “The human called him something like ‘Mittens’ or ‘Sweetie,’ right, Helico?”

“No,” Helico replied with the hesitation of knowing that you’re in a special case where the truth is the worst lie, “she called me by my proper feline name. It was really weird to be honest.”

“What did she say to you?” Lumi demanded.

“She said ‘Hello, my friend, Helico.’”

“And what did you say?” Porto asked.

“I said, ‘Hey, how’s it going?’ Then she walked away. I didn’t pursue it. I was a little disturbed by it to be honest.”

“The reluctant prophet!” Jura shouted.

“I am not a prophet!” Helico shouted, deciding to end the fiasco.

“Look! He’s doing it!” Lumi shouted, “He’s being reluctant!”

Jura started chanting “Tropo! Tropo! Tropo!” and soon most of the cats were joining in.

Helico and Jura exchanged looks. Each had an opposite expression that acknowledged the same truth. Jura had, once again, played the crowd and won the scene. The small ember from Lumi’s spiral-like open-mindedness was fanned into a forest fire by Jura’s wicked paws. Helico had learned that the first cat converted to the lie was Jura herself. Suddenly, Helico felt more than Laika’s life depended on the success of the mission.

Porto was not chanting with the others but pivoted his stance to skeptical agreement. When the other cats had quieted down he asked, “Okay, we’re going to reach into space and save this socialist dog. How are we supposed to do that, Helico? Do we even know where she is?”

Jura had just realized that she never actually asked Helico his plan, just had a blind faith that Tropo would make it happen with magic or whatever. What if he didn’t have an answer? She hadn’t calculated the political consequences of Helico not being Tropo. Suddenly, Jura realized more than Laika’s life depended on the success of the mission.

Helico answered, “Well, Laika is in the stars.”

“If she’s in the stars, then why are we talking about this in the day?” Porto asked.

“Well, I was thinking we can build a tower to get to her during the day, when we can see what we’re doing, and then wait for the stars to come out at night.”

The chorus of cats let out variations of “Oooh,” “Of course,” and “That just might work.” They may have responded in the opposite if they weren’t just a bunch of cats.

“I have done the calculations,” Helico said, “I have climbed the tallest tree in our territory, and I have yet to touch a star. I’m afraid the stars may be two or even three trees high.”

Jura’s relief that Helico was clearly showing the level of competence needed to run a feline space program was replaced by her fear of falling. One tree seemed like suicide, but going multiple trees high? When a god asks you on a quest to the stars, is it bad form to say that you’re afraid of heights? Jura decided to just play it cool.

Helico glanced at Jura, and she looked like she was gagging on a furball. He assumed the cause was Jura’s fear of getting down from trees. He gave her a comforting look then said to her and the crowd, “Don’t worry. A tree is too unstable and too short of a starting point. We may want to get to the top of this office building and start building a tower there. We can prop open the door to the stairs with a stone and then get to the roof.”

Jura’s stomach relaxed as that statement took care of all her worries. Heights were fine as long as she had a way down like stairs. Jura assumed Helico read her mind with divine powers because she had assumed she had done an expert job concealing her unease. So he was probably a plural god incarnate after all. Everything was right and approved by the heavens, and nothing could go wrong.

Helico had long ago learned that you can put a stone in a doorway, and humans won’t remove it. They assume the person who put the stone there was propping the door open for some reason. Humans assume that by removing the stone, they do more to cause trouble than to help.

As fate had it, the roof was prone to leaking and a contractor was being called out to fix it before winter. The janitor had let the contractor onto the roof. Breva and Lumi followed closely behind them, positioning pebbles in the doors before they could close. One pebble for the ground door and another for the door on the roof. The men left. The contractor assumed the janitor left the doors ajar and the janitor assumed the contractor had done it so he could work without asking for the keys all the time. The contractor, in contractor fashion, said he’d start work immediately, but did not return for weeks. Throughout the week the timid janitor just assumed the contractor was still using the doors. So by a woven tapestry of causation, the cats were left to their project.

Helico wanted to rush to the roof to start building. Jura delayed asking that larger rocks replace the pebbles holding the door open.

“We don’t have time to spare cats on that just because you’re afraid of being stuck on the roof,” Helico argued.

“With cats going to and from getting supplies, someone is going to kick the small pebbles out. We need to spend time getting large, sturdy rocks,” Jura said.

“If we’re going to have rocks, it would be a better use of time to use them as building materials,” Helico insisted.

“You’d better hope there’s enough material to reach space on the roof because when we inevitably get trapped up there that’s all we’ll have to build with, and the only thing we’ll have to eat is Laika’s suicide kibble,” Jura argued.

“Why don’t we have Tropo bless the pebbles?” Lumi suggested.

Jura glanced at Helico to see if he thought this would work. His uneasy silence made her think that either Heaven didn’t work this way, or perhaps Helico doubted his own holiness. Either way, Jura felt Lumi’s attempt at helpfulness contained an accidental threat. If Helico blessed the pebbles and they got moved, the cats would lynch her and Helico. Jura was not going to get killed over someone kicking a stone out of a doorway. Glaring at Helico, she said, “Heaven helps those who help themselves, Lumi.”

“I-I was just going to say that,” Helico added.

“Alright, do it the dumb way,” Lumi said.

The roof was nothing special. It was a cracking, flat roof of a commercial building. The building was rectangular in shape. A small brick wall ran along the perimeter. There was a step-ladder and some paint buckets. Helico stared at them trying to figure a way that cats could use them, but he couldn’t think of anything. While the ladder seemed like a good short-cut, the A-frame design didn’t seem like felines could set it up. Their pile of stuff to the night sky plan would be their best option to reach space.

Dyna was the cat put in charge of the stones in the doorways. The first was easy. She just used her massive strength to bat a rock to the building. The hard part was scooping the second rock up each and every step. By the time both stones were in place, the other cats had put one foot of height to the pile. So far the structure was built from sticks of varying sizes, a woman’s glove, and a waffle cone.

After a day of seeing cats walk up and down the stairs past her without offering any help, Dyna was done with this project. “I have just done the most Sisyphean bullshit a cat can ever do. I carried a rock up some steps. It even rolled down some! And your amazing structure is just some sticks and a waffle cone?!”

“It’s just a start,” Jura intervened.

“This might take more than one day,” Helico admitted.

“I’ve let you live too long, Jura,” Dyna threatened, “I don’t have what it takes to lead these trash mammals, but if you’re making them carry rocks up steps and use their sticks to make a path to the sky, then you’ve been allowed to live too long. I want to see what this is all for!”

Though Dyna didn’t use her claws, she made sure smacking the fierce Jura to the side knocked the air out of her.

Dyna made straight for the pile. Helico tried his best to shield their project. Jura started making a few winded paces for the door in case the scene played out as she was expecting it to.

“You don’t understand I’m putting this together in a special way,” Helico pleaded, “You can’t disturb it.”

Dyna ignored him, knocking him to the ground with her chest and then walking right over him. She took a seat on the pile. Peaking over the small wall around the building, Dyna saw the twinkle of the city below. It was a diorama of mighty man in miniature. “I was wrong,” Dyna sobbed, “Everything, the buildings and city lights that were so big, look tiny like stars. That means we must be halfway to the stars.”

“Exactly!” Helico shouted, pulling himself off the floor.

Jura snuck behind the crowd of worker cats. Taking a deep breath, she shouted in a disguised voice, “But Dyna attacked Tropo!” Then again in another voice “She must be killed or this project is cursed!”

“No! What can I do to make it right?!” Dyna pleaded, “I see what this is about now. I’m completely loyal.”

Jura worked her way to center stage, “I’m sorry, but it seems like the crowd knows what needs to be done.”

“Sorry, we have to kill you, Dyna,” Lumi said.

“Let’s make it quick,” Breva said.

“It’s a shame. With her gone I’m going to be the only one doing any heavy lifting,” Porto said.

“Wait!” Helico said, “I forgive her. Heaven says, ‘Don’t kill her. She knew not what she had done!’ Heaven says it’s fine as long as we all work hard on the structure.”

Jura stepped to Helico. “What she did needs to be punished. She is powerful and dangerous.”

Helico said, “What Heaven just said cannot be unsaid. Dyna’s faithfulness to the cause will be rewarded.”

Jura’s fur bristled, “Dyna, you can help Porto bring heavy things for the rest of the project.”

Dyna sucked her teeth, “Like you weren’t already using me like that.”

Jura, still struggling to breathe, licked her paw in feigned apathy and deafness.

***

By November 6th, the pile had begun to grow wider in order to keep growing taller. By this point, it was about five standing cats tall, or almost two stretch cats. When Helico woke up from a nap, he saw that Jura was taking pieces down. “Jura, what are you doing?!”

Jura said, “The cats are out of loose things to build with. They’ve started using meat.”

Helico shouted, “What’s the problem? Now we have something to feed Laika when we get her down.”

Jura said, “The meat is greasy and will decay. You don’t want it to be something you build with.”

“We need the mass, Jura. All the mass matters.”

“We need structure. And if the cats are bringing us meat, then what are they eating?”

“I asked them if there was a way to spend more time on gathering materials and less on hunting, and Lumi came in with some religious zeal and demanded that the cats start fasting.”

“Fasting?! They’re working nonstop and fasting?!” Jura asked, “These are not self-sacrificing creatures. They’re individualists and materialists. We already asked them to stop napping and stop using catnip. We’re pushing this too far. Why didn’t you stop it?”

“I actually agreed with Lumi. Time is, after all, an issue.”

Jura got into Helico’s face, “We’re going to have a mutiny on our paws, and we’ll lose a lot more than time if—” Jura remembered her rule to always assume there was an audience. She casually looked around. She glared at a glow of waxing moonlight bouncing off two tiny ears pointed in their direction. Their owner noticed the silence and decided to reveal themselves.

“Is there a problem?” Lumi asked popping their head into view.

Jura noticed they were asking Helico, not her.

“We decided the fast is over,” Jura said as an announcement to all the cats, “Please, everyone eat the meat off of the bones in the structure, and then return the bones when you’re done.”

A cheer went up among theclowdery crowd. The cats in earshot took to dismantling the tastier parts of the tower. Helico looked on in horror shouting, “Wait!”

But none of the cats listened. They were too eager to start eating. The exception was Lumi who leapt from the top of the tower, pouncing near Jura’s position. If Lumi wasn’t half her size, Jura may have even flinched. Lumi demanded, “Why has Heaven changed its mind?”

“We have shown enough devotion,” Jura said, “Heaven needs us strong now.”

Lumi wagged their tail with violent chaos. Jura kept her tail flat to show she was not pressured by Lumi’s anger, that Lumi could die mad without concerning Jura in the slightest. In truth, Jura was wondering whether they had taken the collar off of something they shouldn’t have. Maybe Jura should have just told Helico to leave Laika to Heaven. Lumi finally had enough of the tense silence, “I’m going to go back to gathering.”

“You should eat something,” Jura insisted, “It’s time to break fast.”

“Heaven will keep my belly full,” Lumi said. They looked to Helico, “Right?”

Helico nodded with a smile, “Just keep working, and you’ll be fine.”

Jura waited for Lumi to disappear over the rock that propped open the door. She looked Helico up and down as if the way in which he looked physically would confirm what she was thinking, “I think I made a mistake about you.”

Helico was smart enough to not be lured into telling on himself. He wasn’t sure what part exactly Jura had a problem with, but he didn’t feel like there was anything to gain by defending the wrong thing. “How so?”

Jura looked around. The other cats were too busy eating, but she decided to push Helico away towards the corner by the ladder.

Helico didn’t care for the shoving, but he also appreciated the safety in privacy. Only now while redoing his social-math was he realizing that his inviting her to elaborate could be considered a challenge. But the display of loyalty from Lumi might have implied a change of dynamics in Helico’s favor. Could the devotion of one spiral cat to another really be an accurate reading of the more normative ones? The grim prize for round off error was a premature trip to Heaven. It was an age old question, who had power here? The one in charge of law or the one in charge of the stories of Heaven? It was a question far more ancient for cats than it ever was for humans. If Jura lost faith in his being Tropo, then there wasn’t much keeping him alive. She might kill him out of pure humiliation, or to save face with her cats. The opposite problem was if Jura believed the stories, then she’d believe that Tropo could be brought to suffer the inconvenience of reincarnation. Jura was definitely the type to try and kill a deity.

Not that he needed the reminder, but a shooting star at that moment pulled his attention to the fact that Laika’s time was waning. Tomorrow was the full moon and the ignorant cats were going to let superstition spook them. He would need Jura to rally them, but after asking the cats to put their meals into the tower and not into their bellies that would be a tough sell. He wasn’t even sure Jura was believing her own lie anymore.

“You’re supposed to be here, able to bridge the gaps and overcome. But you’re begging for a mutiny,” Jura whisper-shouted, her nose pushing through Helico’s whiskers.

Helico ran the social numbers on saying “I never said I was Tropo. You’re the one who wanted to believe I was Tropo so much!” The math came back with the conclusion that any response that called Jura out for her mental lacking was not wise. Though, the calculations may have been skewed by the threatening way that Jura was breathing hot in his ear and pressing him against a cold metal ladder. Helico just sat silent, his tail wagging in frustration. There was a tower to build and a life to save. Why was he being wrapped up in the stupid politics of a bunch of cats? Why was this one cat insisting her spiritual psychosis spill all over the project? It wasn’t his fault she just assigned him a role in her mind. What if he had done it to her? What if he actually did do it to her? Helico asked, “Do you know which god you remind me of, Jura?”

“Tropo?” Jura squeaked, knowing the answer she hoped for was not going to be the answer he said.

Helico tried to stifle his laugh, but the laughter hit him quicker than his self-preservation. “Did your mother ever tell you about Morsa?”

“I didn’t have much time with my mother. She never got to that one.”

“Then you get to hear a new Old Mewing,” Helico said.

Jura backed away a few steps from Helico’s face and lay down, but avoided eye contact. “It better be a true Old Mewing. I will ask the elders if you’re trying to manipulate me.”

Helico sighed, wondering where this spiritual fact-checking attitude was earlier, though maybe it was just a warning that Jura’s faith was failing. “Don’t worry this was my favorite one as a kid.”

“Once upon a time, all the cats had thrived as immortals. These were the dark ages. Cats aged, and their bodies broke, and there was no end to the pain. When Morsa’s mother’s body broke years too early, the mother feared the eternity of pain. Morsa was deeply wise in the sciences of spirits. She discovered something that could be done, death. She would take those who didn’t want to be anymore and take them where they didn’t have to. She called it a sleep without dream. Morsa was the hero of cats and brought in the golden ages. Heaven rewarded her with eternal youth and health, ironically making her immortal for creating death. Soon everyone forgot what life was like without death, and Morsa was seen as a villain. Cats would learn healing to defeat her. The only ones who showed any want for her just wanted to shake off the painful parts of life. She became indifferent to the cats and began taking anyone, not just those at the end of their time. What did it matter to a friendless deity with no worshipers?

Eventually, one day, Morsa wanted to create instead of destroy. She made an aesthetic arrangement of string. A couple of cats were the first to view it. As they quizzed the tapestry, Morsa would cut in with insecure additions to try to sway the audience’s opinions, “I colored the string with blood,” “I used saliva and dirt to control the tone to create contrast,” “I think it was a daring choice to break the rule of thirds.”

The couple nodded politely.

It was the first time since Morsa’s apotheosis that she faced being laughed at, or worse actually connecting with other cats. She couldn’t handle giving that to whatever mere feline who happened by her tapestry. Morsa filled the room with a deadly disease, and before the cats could comment, the couple had died. Morsa transfigured their corpses to ash and swept them away, pocketing their souls for later delivery to nonbeing. Morsa’s gallery showing continued in a similar manner until eventually cats stopped coming to see Morsa’s work.

In the end, Morsa realized she hadn’t gotten what she was looking for. The neutral nothing of no reaction was worse than the possibility of laughter. At the gate to nothing, Morsa hesitated. She opened her pocket and asked the souls of the cats who had seen her tapestry what they had thought. All the responses were similar, “Even the worst thing I’ve ever seen didn’t kill me. That alone makes the worst art better than this art that killed me.”

Morsa tried again with a new tapestry, but nobody dared to come. Ultimately, the only creation Morsa was capable of was death. Some say whenever there is a cat whose only benefit is how she can destroy, then that is Morsa incarnated.”

Jura sat with the message of the fable for a moment. Finally, she said with her words dripping in restrained grief, “So you’re saying there’s something wrong with me. So what? Maybe I’m not the blessed reincarnation of Tropo like you are.” Jura’s ears fell flat, and she spoke with her eyes closed, “I want things to be done right. I want to save the dog that’s up a tree. I’m…” she paused, “…not ruining things.”

“You’re the only one seeing problems. You’re the only one telling us to tear down parts of the tower,” Helico said, “The only one without faith. What did you do to make Heaven give you such a hard heart?”

Jura wanted to argue that she kept the doors from closing on them, but she couldn’t actually prove that the pebbles wouldn’t have held the doors. Maybe the lack of problems with the doors was simply because there wasn’t any problem to be solved. Maybe she did ruin everything. Maybe she was just wasting time. Was she going to end up killing Laika? She only knew how to manipulate and kill. This tower was the only positive thing she ever tried with her life, and doing things her usual way was maybe ruining it. Maybe she needed to be less herself.

Wordless, Jura buried her face under her paws. Helico had overplayed his hand, but Jura’s complicated relationship with Heaven and herself left her without the chips to call his bluff.

Lumi returned with an iron-on patch for a poodle skirt, “Look what I found! It’s a sign!”

Helico reasoned that Heaven would forgive his masquerade, or that maybe he truly wasTropo. After all, Jura had good reasons to believe he was the deity. And so far there was no situation he couldn’t talk his way through. With just words he managed to destroy Jura, the best of cats, empty her of her power. Maybe up until now, he’d been too timid. Time was running out, and the story he had just finished reciting told him that a cat like Jura, who lives by death, could only be dogged by failure. It was sad that for as long as he could remember he had an ill-advised crush on Jura. But now his own tactic manipulated him into seeing her only as Morsa, a sad deity. Tropo however was the transcendental power of the thesis and its antithesis. The feminine and the masculine. The cat and the dog. Lumi the faithful had brought light to the new direction of this mission with a picture of a dog.

“You’re going to need faith, Jura,” Helico said, “Even when what we need goes against everything your logic says.”

“I want to be better,” she whispered.

***

Helico was missing the morning of November 7th, the day of the full moon. Superstitious mutterings spread through the cats.

“It’s fine,” Jura said, “Just keep working. He’ll be back soon.”

Cats would come to Jura asking whether what they found would be good or not. Jura had her thoughts but just said, “It’s fine.”

Jura had to reluctantly admit that simply saying yes to everything that the other cats wanted to do was getting a lot of height done on the tower. The cats were doing simply what they saw was best and the team effort was working. Lumi started taking from the width added for support and going for height. While it was against Jura’s judgment, the tower was getting taller. She had to have faith that Heaven would not allow someone to tilt the tower over. Ignoring the tidal forces pulling and stretching on her anxiety, Jura ordered Dyna and the others to help Lumi. Jura was going to have value outside of thanatos. She faked a smile as if saying “See, I am capable of eros, of creative forces. I am not death incarnate.”

As Porto pulled materials from the base of the tower, Jura thought to confide in him. He was the one who made the winning argument for her ban on drinking the cotton candy water found under cars sometimes. “Porto? Your mom ever tell you the Morsa mewing?”

“Yeah, Morsa always reminded me of you actually,” he said, “Never got your obsession with Tropo when there was a much more Jura-like story. Why?”

“I had a question, but you answered it,” Jura squeaked.

After sunset Helico returned, assembling all the cats. The full moon had already risen to add a grim and delightful white glint to Helico’s whiskers. “I’ve heard concerns that, despite our work, the stars do not seem any closer. It’s as if they move away as we get closer. That’s just an illusion. I, Tropo, can take us to the stars, but we need to work harder. So I brought harder workers.”

Through the propped open doorway to the roof, two dogs appeared. Each feline hair bristled, except for Helico’s. “This is Jack London. And Jura, I believe you’ve met Bruno.”

Jura stepped through the crowd. As she passed Dyna she said, “Stay close.” Despite their friction, Dyna knew to do what Jura said. When in mortal need of shenanigans, even Achilles follows Odysseus.

Porto saw Dyna follow Jura on her left flank. He joined on the right flank. Lumi slipped along the sides to watch from the front row. Breva took the shortest route to the top of the tower, deciding to opt out of whatever was about to happen. A-Cat-Whose-Name-and-Significance-No-One-Remembers did something as well.

Jura thought she’d try to have faith in Helico’s plan. For his plan to work, she was going to have to choke out the conflict. “Bruno, my dear friend,” Jura said to the eggshell white dog whose fur screamed of moonlight.

Jack London interrupted her. “Jack London is Jack London. This is Bruno.”

Jura looked this time at the gray dog. “I hope you’re not holding a grudge about that gentle teasing I gave you the other day. As you can see we’re hard at work to save Laika. A favor of good will to dog-kind.”

“You were laughing. You said you’d have kicked all of dog-kind back into ‘God’s balls’ if you could.”

“Bit of a misunderstanding,” Jura said, pausing to figure out how to spin the situation. “I thought dogs loved a bit of casual talk about genocide. Your favorite type of humor I’m told. ‘Only good cat is a dead cat’ is my favorite canine bit of satirical commentary.”

“I told you I was a moderate.”

Jura looked to Helico who offered, “An apology might be a start.”

“You called Lassie a bitch-whore,” Bruno said.

The cats tried not to snicker. Bruno’s canine companion Jack London growled, and the cats found their composure quickly.

Bruno added, “You responded to my death threats with, what I later realized was multiple perverted sexual innuendos, which were not at all appropriate.”

“Okay, so I’ll apologize for the comments, and you’ll apologize for the death threats and actual intent to take my life?” Jura asked.

Bruno and Jack London growled. A drop of drool fell from Bruno’s teeth.

“I understand the situation,” Jura said.

“You also—” Bruno started.

“I waive reading of the charges, your honor,” Jura said, “If it pleases the court, I want to apologize for how I clearly hurt your feelings.” Sarcasm aside, this was actually Jura trying to show civility and respect to a dog, albeit at the barrel of a gun or canine equivalent.

“I’m not a fragile snowflake!” barked Bruno, “You couldn’t hurt my feelings!”

“Um, well, then I’m sorry what I said was offensive.”

“I’m not easily triggered,” Bruno said, “I wasn’t offended.”

“Well, then it appears we have no grievance!” Jura said, losing patience.

“You said horrible things!” Bruno shouted.

Jura had ironically realized that she wasn’t going to get out of this by showing respect. Fascists were obsessed with power and hierarchy. She couldn’t handle this with a sincere apology, so she just echoed back the last thing they said with an apology prefix and hoped they were stupid enough to accept it. “I’m sorry, I said horrible things.”

“You were rude and uncivil.”

“I’m sorry, I was rude and uncivil.”

Bruno and Jack London’s tails started to wag. The beef was squashed.

“Excuse me, I need to clean myself,” Jura said, moving slowly and whispering to Helico. “These dogs are violent, unstable, and racist.”

“I told you to have faith even when it goes against your every bit of logic,” Helico said, “Remember I’m Tropo. I surmount the insurmountable.”

Lumi stepped in front of the dogs, their bright fur outshining the moon. “This is a great day of miracles and proof that we are living in the light of Tropo. Imagine canines and felines working as equals!”

Jack London growled, “Jack London believes you’ve insulted Bruno and Jack London.”

Jura asked Helico, “What are Jack London’s views on race?”

Helico replied, “Well, we know Bruno is a moderate. I also know Jack London is a socialist, which is why Jack London wanted to help us save Laika. I don’t really know his views on race.”

Clearly hearing all of Jura and Helico’s sidebar conversation, Jack London said, “Jack London believes in genocide for the lesser breeds. Jack London believes in eugenics.”

Lumi gave an awkward laugh, “But the old mewings say that cats are the highest predator and even once almost made canines extinct in North America.”

Jura sighed, “I hate all this science racism.”

“May Jack London retort?” Jack London asked Helico.

“I think it would help to bridge the distance between us to have an open discussion of our biases,” Helico said.

Jack London stepped to Lumi, who didn’t flinch. He towered over them, but as they stood in the moonlight shadow of death, they feared no evil for Lumi always carried their own light. Lumi simply existed without fear. Jack London took this personally. In a flick of a whisker, Lumi was in the dog’s mouth and in one bite their life was punctured. Their emptied body dropped on the ground as a testament to racial supremacy.

“Eyes!” Jura shouted, already paw-deep in Jack London’s left eye.

Porto flanked around to Jack London’s right eye, but his swipes only caught a closed eye-lid.

Dyna hesitated. “What about his friend?” she asked, “He’s a moderate.”

“Fuck the fascist’s friend!” Jura shouted.

Dyna jumped over Bruno’s face, grabbed hold of his nape, then started swiping at his eyes with her hind legs.

Bruno wailed, “But I’m a moderate!”

“A moderate between what and what exactly?!” A-Cat-Whose-Name-and-Significance-No-One-Remembers said, and then clawed or bit Bruno on his tail or leg maybe. Then all others who were brave joined in the fight as well.

Bruno ran straight ahead to shake Dyna off of him, headbutting her into the tower. As the tower leaned over the edge, every creature paused to witness its fate. Breva leaped from the structure, providing the last bit of force to topple it off the roof, clattering to the ground. They stared in horrified silence as all but the first few hour’s worth of work was gone. Not reading the scene Breva said, “Wow, I almost died.”

Bloody, the dogs decided to leave. The cats weren’t militaristically capable of the revenge kill to make things even. Jura knew that beating your opponent to the point where they learned not to fight you was a win and left it at that.

“So what about Laika?” Breva asked.

“Laika will be as dead as Lumi,” Jura said. Saying cruel things without a laugh or without anger was the closest to saying “I’m in very real pain” that Jura was capable of.

“We can still make this work,” Helico said, “We’ve had some setbacks. But I have another plan if you can help me with the ladder over there, maybe—”

Porto interrupted by licking the bridge of Helico’s nose and disappeared into the darkness behind the door propped open by the rock. As each cat left the roof, they came by and licked Helico the same way. They were voting. Each lick was a cat vowing responsibility for the murder of the licked cat. Dyna pulled down Jura’s head and licked from her eyebrows to her ears. Dyna then licked Helico on the bridge as she left. Helico, by unanimous decision, would be killed on sight for falsely representing himself as a god. Jura was challenged to a fight to the death. The same sentence with different executions.

Helico rattled around with the ladder, “Jura, if you help me we can still save Laika.”

Jura said, “Even the ladder won’t get us three trees high.”

“Maybe, it doesn’t need to get us all the way there if Laika can reach down and meet us halfway.”

“I’m sick of dogs.”

“What about Laika? What about creatures stuck up trees?”

“You were supposed to be my Deus Ex Machina, you know?” Jura mewed, “You were supposed to make all my life have meaning. If Tropo could come and touch this dumpster cat’s life with some grand quest, what an amazing fucking life would that be? But I’m broken, I only know how to destroy things, and it’s too late for any god to fix that.”

Helico ran to Jura as if convincing her was a matter of proximity. “If you help me set up that ladder, you can still have that life.”

Jura walked towards Lumi’s body and licked the bridge of their nose. “How dare you promise me the ability to undo any cruelty in this world?”

“We still can!” Helico shouted, “but I can’t do it alone.”

“You’re not alone; you have your devoted Lumi,” Jura said without anger or laughter. Helico followed Jura to the darkness of the stairwell. Her eyes glowed from the moon now in its zenith, “Each cat volunteered to kill you. If you reach Laika, it’s probably best that you just disappear with her wherever she’s going.”

“You need to have faith again. I always believed you were the best of cats,” Helico professed, “I would dream you could love me.”

Jura mewed, “I thought you were a god.” She licked the bridge of Helico’s nose, and pulled the stone out from the doorway. As the door closed, she saw no fear in Helico’s face.

The mewings say when Dyna defeated Jura that Jura was unable to swing her claws at Dyna. Some say for Morsa to escape her being herself, she needed to create. Unable to create, the only way to find peace was to choose not to destroy. They think Morsa found an escape from her legacy of killing, in her last moments as Jura. Others say an immortal spirit of pure thanatos cannot escape the death drive by letting itself die; whatever was accomplished in the life of Jura was not of use to any gods, and that’s how it goes sometimes.

When the contractor arrived weeks later, Breva and Porto went back to the roof the instant the doors were opened. They found only Lumi’s mummified body and an upright ladder.