She sunk her hands into the red clay, and scooped up a piece like a hunk of meat. It was cold, deathly, something not yet living. Her eyes squinted as the afternoon sun invaded her studio from the west. It would hit the pyramids soon, and be broken into shards of deviating light, but for now it was concentrated into one thick plank, smacking against the rooftop window.

She smoothed the clay onto her subject, around the tough sinewy throat, sweeping upwards to the chin, pinching a cherry cleft between finger and thumb; then up to the cheeks, with their parched bones, filling in the gaunt, hollow eyes, caressing. The face captured a strange look— frozen, somewhere between sadness and exasperation, a person not ready for a sealed fate. She stepped back to look at her work: beautiful, even without embellishments. So different from the amorphous figures lining her shelves, nothing like her ghastly wire forms and haunting reliefs. But this wasn’t just art. It was a salvation.

Basil wrote: Feb 4th, cold: Madiha had until Valentine’s Day—a self-set deadline: a statue of a fiancée, missing since the engagement. Devastating.

But Madiha knew the best medicine for a broken heart: a commemorative piece to grace the living room, a piece of forever, the beloved in a cast.

It wasn’t her first project. The first had been that schoolgirl, two years back. November 22nd, chilly: waist-length hair and musical talent strayed from a bus on a Sakkara school trip, never seen again. The school kept the sculpture as a memorial. The parents couldn’t bear the resemblance; it was too real.

And the footballer. People think footballers are at risk of ruptured spleens or massive kicks to their head or scrotum. Not this one. March 12th last year: breezy. Farid H. disappeared, and left behind a trail of personal effects—watch, ID, a sweatband, an odd sock. His wife said he had always been the depressed type. Suicide or homicide? No clue. No trace of a body. His wife loved the sculpture. An incredible likeness for someone the artist had barely know.

How do you know these people, Madiha? Mind your own business, Basil.

It was time for coffee, Madiha decided, or should she wait for the call? No, coffee now. Maybe she should stop taking his calls. She wiped her hands on the filthy rag and went to fill the kettle from the tap, looking at her reflection in a speckled mirror above the sink. A face that had never been adorned. Or adored. Her features were disturbed by a lacy web of black, where the silver foil beneath the glass surface had eroded. It was like a nest of spindly spiders crawling over her face as she moved. She pushed back the little headscarf and her snaking dreadlocks, as if looking for an excuse; they squirmed out, struggling for dominance.

Dominance. She clicked the kettle on, and pondered a smoke. No smoke. A stick of Indian jasmine, instead, to sweeten the air, was wedged into the window sill. Her hair jiggled as she struck a match to the long taper of incense.

Jiggly hair. It had been jiggling since middle school.

Ya Madiha ya binti, won’t you even consider a different style? Hair straightener? It’s not feminine. You look like a madwoman.

Or an alien.

Or a devil.

Papi would know. He died silently disappointed.

That daughter is becoming such a mess after her Papi’s passing. Nothing like Amy. Maybe it’s depression.

No, no, they weren’t even close. She was evil-eyed, early on. Remember the soft baby curls? Those symmetrical eyes, shiny as black olives, the pip-sized nostrils, those jelly-soft cheeks? All gone! An evil-eye will shatter stone! Poor thing. Will she ever find a husband?

None to be found. No one liked what they saw. She wasn’t an Amy. Nose went splat, obsidian eyes went squint, and cheeks embraced acne scars. Then Madiha added her own magic: dirty nails, an expression set in stone, and an obsession with weird art. And wild hair.

She loved the English name for her knots. Dread. Locks. Imprisoners of doom. Madiha’s doom. In Arabic it was just dafayer – braids – not daunting enough. No power in them; you don’t get tremors from a schoolgirl’s plaits in white ribbons. But dreadlocks were her armour. They kept everyone at bay.

It’s not feminine. You look like a madwoman.

Everyone but Basil. Look what Papi’s love did.

So she wasn’t going to study medicine like Papi? Engineering like Amy? Law? Business? No. Art. Hands-in-the-mud art.

It’s a phase.

It’s a bad bunch. It’s rebellion.

It’s a curse.

Her cell phone rings. Basil. As brave as his name. Great at sneaking up, like a snoopy sales assistant in a tawdry downtown shoe shop. Remarkably lanky. Where-oh-where did you come from Oh Wonderful Bassoola? Planted like a bug, perhaps, by an old auntie because Madiha hadn’t found herself a nice man on her own, and wasn’t going to sit down in a salon to be inspected anymore. He had just shown up and said he wanted to take pictures of her artwork. She gritted her teeth.

Pictures? Fine.

That’s what photojournalists do.

And then he was always there, through the seasons, showing up outside her studio, to carry supplies up the steep six floors; to poke around with sales to her private clients, to set up her exhibits in tiny galleries. And she found herself letting him. Greedy eyes, scouring her artwork, wandering everywhere but to her face. Had he ever even seen her eyes?

Are you an art freak? Show me your reviews.

All in good time, Madiha.

Soon he made her buzz. Just a little. Her heart started doing those stupid “skippy-leapy” things that hearts do when in love.

Was she in love? Didn’t want to be. Love exposed you and then you fell. Look what Papi’s love did.

Hello? Busy? Always busy.

Can I come over? Basil, I have work.

I have work too. But I thought—

I have to finish this project. Can’t I see?

No.

As you wish.

The kettle screeched and clicked off. She poured the water over the instant grinds, swirled it, a little too violently, and plop, a little scald of it licked her wrist.

Damn!

She walked out onto the grubby rooftop. It was freezing. She edged up to the kiln in the corner, still hot after a day’s burning. A little twist of white lace fluttered at her feet; she lifted it and tossed it into the kiln, watching it fizzle to a black thread, then to nothing. Basil should be nothing. His questions were too many.

Why don’t you do more of these life-like sculptures? You don’t like my other work? It’s different. Bizarre? Very bizarre sells. But the realistic sculptures are incredible. You could make a great name for yourself. And a lot of money.

I don’t need money. What are these stuffed with, Madiha? Stuff.

What stuff? Show me. Show me yours.

He took out an envelope, filled with black and white prints.

They’re all people.

I like taking pictures of people. Your subjects don’t know you are there.

Neither do yours, Madiha.

She shuddered back into her studio, and faced her sculpture. Yasmina, the beautiful. Swaddled in robes like a Diana. Poor droopy-eyed fiancée.

Loss is so hard. Madiha knew. Hadn’t she lost Papi—over and over and over, like tumbling down a forever staircase, floor after floor after floor? He’d let go of her hand when she turned out different, and after that, she had just kept falling.

When he died, it was like landing— finally—all broken.

The phone rings again.

Hello?

I am downstairs. I have to see you, have to talk, have to—

She jerks the phone away from her ear and looks at it as if it is a swear word.

Hello? Madiha?

Poke. Poke. Poke.

He knows. Of course he knows. She knew all along that he did.

Madiha slushed down the rest of her coffee. The sun was splintering the pyramids now, stabbing the vulnerable skyline, bleeding into the smog-sodden clouds, making them an awkward, dirty, bruised pinkish-blue. He’d be up in a minute. She looked around her studio— nothing extraordinary, just wire and stones and clay.

Did Papi know how it hurt, the doctor who didn’t understand pain? Maybe he would be proud of her anatomical accuracies now, perfectly dissected, dried, wired, wrapped. Embellished. When we can’t embellish ourselves, we embellish life.

The door creaks. No need to knock.

Madiha sits on the stone floor. She looks at Yasmina. Almost done. Three, maximum four days. Then she’d bake her, embellish, and serve.

Basil squats.

What is it you do, Madiha?

I enhance life. But why do you ask when you already know? Isn’t that why you came? He looks her in the eye.

I don’t do multiple projects, Basil. She reaches out, as if to kiss his ear, but touches his throat, and grasps the protruding tendons of his neck. He smiles and cuts her short, and grasps her wrist with a swift flick, catching it with the clink of a handcuff. Neither do I, Madiha.

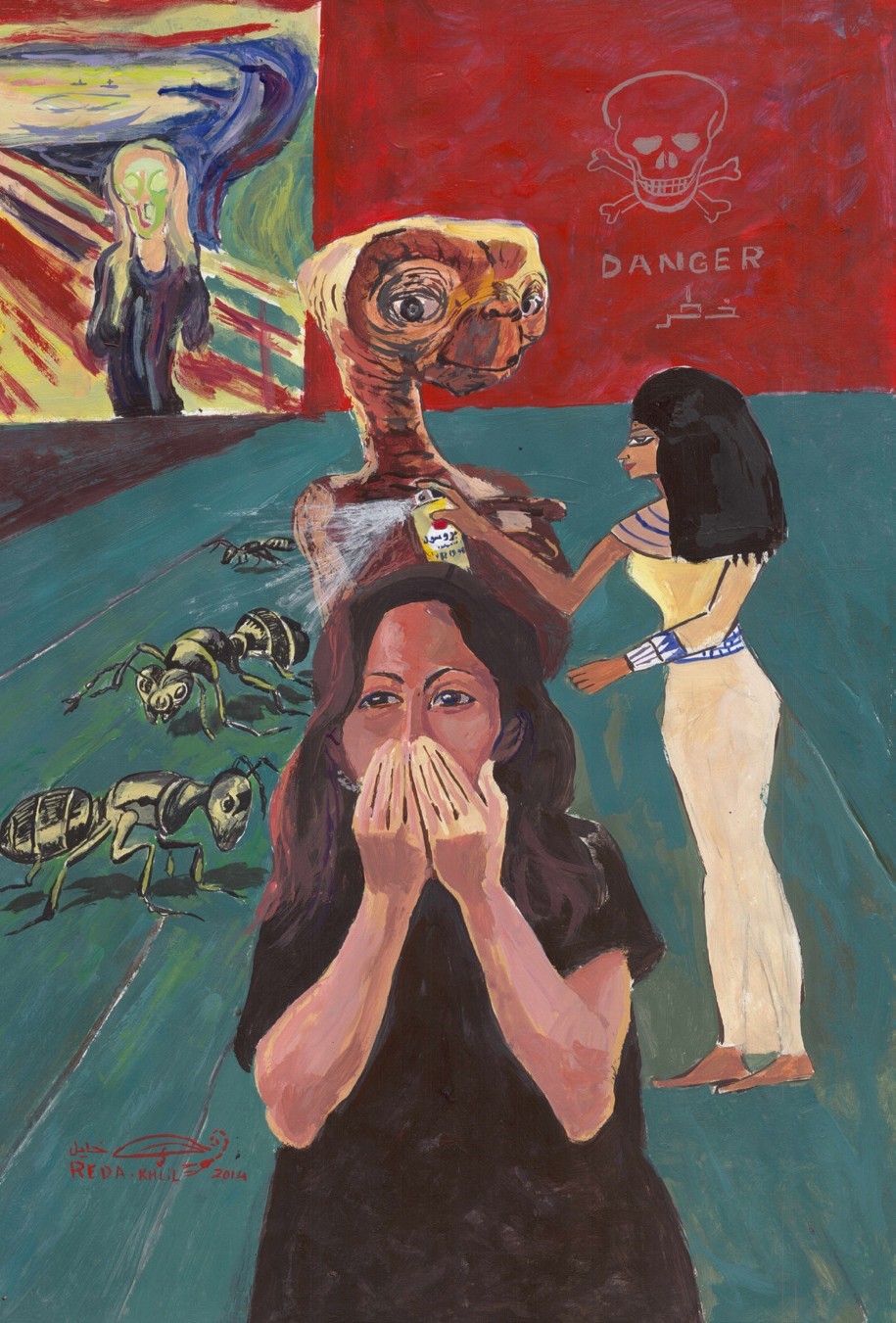

All artwork is courtesy of Reda Khalil.