Away from the bustle and the oppressive, dry heat of Xi’an, at the foothills of the mountains that overlook my city, lie my creations. They still stand today, testament to the perseverance of my subjects, who molded the earth in their own form, testament to the apocryphal gods we are… that I was. And though my empire has not existed in the real world for many centuries, around me, it lives on. Here, I am still emperor, and though millennia have passed, time is yet to puncture this tomb of mine.

In life and in history books, they called me an inhuman emperor, and now, that is what I have truly become. My body lacks signs of life, carrying only the marks of death, each feature victim to decay and time. Just another corpse—animate, unexplained, disconsolate. Sleep has eluded me for over two thousand years. Thirst, hunger, love, and fear are now just words; even their memories are evasive. These are, after all, the feelings of mortals. To be devoid of them is to be dead—this is what logic dictates. But it appears that logic, too, fails to penetrate these parts, for I have lived these uncountable years as an exception to the fact that the dead don’t move, don’t think.

To create is one thing, to protect another, and I have done the more important of these. Every single day, I have paced around this tomb, my mind fixed on one thought: getting out of this—call it what you will…city, palace, tomb…for me, it is nothing but a prison. There is no night or day here, and the only light comes from the eternal blue flames that the fāngshì had initiated by setting alight the air from within the ground. It was an exquisite source of pride then, but that pride has long since waned. Now, the blue flames are just a light that exposes this grand hollow, these endless treasures, and my peeling skin.

A lake of mercury laps against the eastern wall, reflecting the blue flames. Here, the flames and the lake are the only things that move besides me. I had come to think of this lake as a friend. But on the day I inched closest to it, I saw the guifrom hell, staring back at me and I thought that it had come to drag me away. For a moment, I thought I was gleeful, though I could no longer feel it; any escape would be a good escape. I knelt further in towards this gui, its face blackened like burned clay, cheeks sunken and hollow, patched with holes like a beggar’s cloth. Though repulsive, I extended my hand towards it, towards the surface of the mercury lake, and the gui extended its hand too. When I pulled back my hand, it pulled back too, and I saw that its skin was avulsed from the bone. When I touched my face, ittouched its own. I watched it move its hands over its almost bare skull as I moved my hands over mine. And I watched, disgusted, as it thumbed the holes in its flesh, and then I realised that my fingers had found their way into the gaping hole that was once the emperor’s right eye. And it was then that I knew that there was no gui except me, that there was no hell except this, and that for me, there would be no redemption.

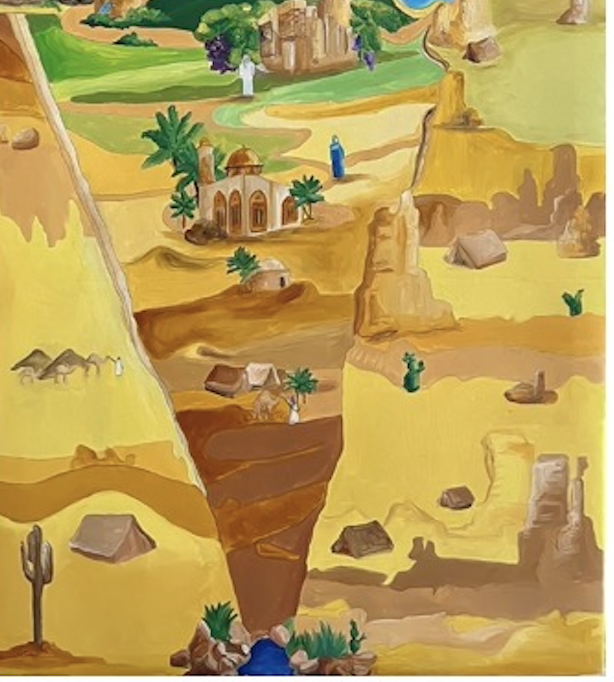

Since that day, I have stayed far away from the lake. This tomb is vast. There is much else to see. At the northern end is a majestic wall adorned with murals, promising an afterlife fit for an emperor. Golden phoenixes decorate the wall and glimmer in the light. Underneath them, covered in gold leaf, I see Mount Penglai stretched out in all its glory. That is where I will make my way once I leave this cursed tomb. In here, there are no chirping birds, no rustling leaves, no blooming plum blossoms or scented osmanthus, no gushing streams, no scented women of the harem, no pleasures of the flesh. Only this rotting, putrefying flesh. This asceticism has been thrust upon me against my will, and I remain an unwilling saint.

Without my soldiers, I would have long destroyed myself. I have a thousand eyes made of clay that look out at the world, a thousand ears that hear. Through all that they see and hear, I have known the passage of time, the changing fates of kings, the fickle loyalties of power.

Today, my shattered army is constantly surrounded, not by a horde of the Xiōngnú as they once were, but by people who visit from all over this nation. They tell their stories—of legends they have heard, places they have seen, and those who came after me—without knowing that they are doing their first emperor a great service, without knowing that their stories are my only companions as I live out my endless days in this crypt, giving me renewed vigor.

Ah, yes. I live through my terracotta men. I see through the terracotta, I hear through the terracotta, I feel every shattered fragment, and I feel through every piece of terracotta. It was through them that I felt the betrayal of Xiang Yu. Snakes will be snakes, and that traitor was undeserving of my generosity. It is my own stable that bred incompetent fools. Even Zhao Gao, my most trusted eunuch, failed me. As Xiang Yu’s rebel army stormed my capital, my heart was singed. When they broke into my tomb, aided by my treasonous soldiers, I was consumed by a long-forgotten rage. But I had little idea of the real pain that was to come. As the traitors set fire to my clay soldiers, I felt the flames lick my skin and burn through my flesh, even though I myself remained uncharred. As the terracotta shattered, so did my bones, only to fuse back together. A million pieces; a million fractures, fused again.

My subjects and plotters have long since turned to dust, but my terracotta men stand. To whom has time been kinder? Who can say? In an ephemeral world, permanence finds itself only in the remains of the inanimate. For the animate, permanence is only a concept, worthy of the ruminations of philosophers, and I, in my desperate miming of life, remain its only proof.

I remember my life, the victories, the losses, the betrayals. I remember the making of the mud warriors. I remember the preparations for my death. I remember the very moment of my death, when my spirit joined me in the grave, and I remember waking again. And I have remembered every day since. There were no placations for me in this sealed tomb. Here, in its oppressive air, where even the sky is carpeted and plastered, I feel my unappeased spirit transform into a gui, I feel myself becoming angry, I know myself getting frustrated. My daily walks are spent pacing. I can no longer see the wealth they buried me with. I have moved it all, trying to find a gap, to find any way out. There has been nothing—no escape except the one door that does not open. That door, beautifully carved, adorned with phoenixes and embossed with epithets addressed to the corpse it houses, teases me every day, leers at me, its own emperor!

My body, too, fails me. Like my terracotta, I am not whole. Not shattered like them, but worse. What is this afterlife that smells? Where is the perfumed harem I was promised? It is by my own orders that they lie at the bottom of their funerary pit. In the early days of my resurrection, I had hoped that they would come alive, too. But they have stayed dead all these years.

Meanwhile, I stare at an endlessness that has no horizon. No beginnings, no ends, only me, only my soldiers, and only this slow disintegration, this decay that gnaws at my bones and pulls at my skin. It is a putrid feeling. I can smell myself and it makes me retch. There is no nobility in the afterlife. If this is the afterlife, it is degrading, it is filthy, it is blood and pus and bile, and it is nothing that an emperor should be. Were it not for the soldiers, I would have long forgotten what it felt like to be human. But I see through their eyes, and I remember the devotion of the hands that made them, and every decade that they stand in formation is another decade that I live, another decade that I remember what I was, and another decade that I relive the betrayal. They buried so many others with me, but I alone have to bear this curse—of life beyond death, amongst death. In the early days, I walked among them, and I did not know if the stench of decayed flesh rose from their bodies or from my own skin. Now, they are only bones, yet the smell of the decay remains. It is me, it was always me—me, the emperor who turned gravekeeper.

I have made numerous, repeated attempts to end my existence. Immolation only blackened me further. Mercury feels like water to the touch. My elixirs are equally incompetent. Suffocation? I haven’t taken a breath in two millennia. I have butchered myself only for my limbs to grow back like vines.

Which other God must I make a sacrifice to to escape this wretched life…death…afterlife? I have consulted my books, the few that have survived, and I find no answers. I have long suspected that my condition is the result of the transgressions and incompetencies of my priests. My soul remains uncleansed, or perhaps their sacrifices were polluted. If only those new monks, the Buddhists, were right; reincarnation would have been preferable to this. Where is their bodhisattva? Here, there is only me, enlightened of my own misery.

Or maybe this is reincarnation. Perhaps I am reincarnate as myself, perhaps there is no other creature burdensome enough to bear this weight of my karma. I must bear the fruits myself, vile though they may be. Mine has been a life few would envy, and many will misconstrue, but was it unworthy even of a crowning afterlife or even a minor reincarnation? Are there gods merciful enough to understand, to find out the truth, and to free me from this tomb of mine that closes over me with each passing day or week or century or millennium? Or have the gods, like the people, been misled in their beliefs about me?

Time has bent itself into a monolith; there is no past, no present, no future. Only my doings stretching before and after me. Laozi was wrong too; “Even heaven and earth could not last forever, let alone human beings.” Fools, all of them. I stand as undeniable proof against their claims. Perhaps I was right to burn down every false word of his and his fellow exemplars.

I have heard them talk, and in my day as well as this one, they still say the same things. They say I am not my father’s son, that I am of merchant blood, that I am illegitimate. How dare they. How dare they think it even matters. I brought this nation together; I made it one, I made it whole. I may not know who my father was, but I know that the fatherhood of this land is mine, and mine alone. I united the zygotic clans that fought among themselves, so that they now call themselves one people. I moulded the earth and raised the Great Wall. It was me, no one but me!

In Wang Bi’s works, I find a meaning to my curse. I’ve had plenty of time for reflection. For over two thousand years, I have had the company of his words, and with each passing century, I have become aware of a greater depth in his work. He speaks of me: “Loud sound is impossible to hear, and a great figure cannot be seen.” I am the loud sound. I am the great figure. I am the Great Uni. Father of the Middle Kingdom. Builder of the Great Wall. Ruler of lands from the Taklamakan to the Yellow Sea.

But look at this, what is this, the one who brought this land together falls apart himself—this separating blood and bone and sinew that peels apart? What am I now? Prisoner, emperor, or fiend? Who can tell me? The one who had brought this land together slowly disintegrates and yet no one comes to his aid. That is all I know.

Through the eyes and ears of my clay soldiers, I have known of the new empires that have arisen in my stead. Many have come after me! A republic too! What is it like to rule again, over the living? What is it like to feel the rush of power through your veins? What is it like to feel the run of blood through your veins?

I wish I could have spoken with him, or spoken with anyone at all. Loneliness is the most unbearable. I have been denied even the sound of my beating heart. For over two thousand years, only my ramblings and my elixirs have given me company. Ah yes, my elixirs. The fāngshì promised me immortality. Fools, liars. Till my last living moments, they served me a ‘life giving’ concoction of mercury. But each sip served only to drain my life away from me. They had left these elixirs in my tomb. When I awoke, there was plenty of dàmá, xiàojùn, làngdàng, and other potions to restore myself. I finished them within the first few days. They passed through me like water, with no effect. Betrayed even by my trusty intoxicants. Ha, fate has never been crueler.

Xu Fu failed me too. Liars all of them. I wonder if he ever reached Penglai and found the elixir of immortality he promised me. I hope he drowned. That would be preferable to betraying his emperor.

It has been over 50 years since my terracotta men surfaced in the world of the living, and since then, the army has been slowly pieced back together. With every shard that is glued back on, my bones grow back their sinew and flesh. Every inch of repair is a resurrection. I feel myself fatten up, like a pig before the feast that would take its life. After millennia, I approached the lake of mercury and braved a look at my reflection. My face is fuller, the patches on the skin have evened out, and my right eye fills its socket—watchful, prepared. I am stronger now. Yet blood and a beating heart have been elusive. Enough shards have been put together, and most of my skin and flesh have grown back. I thought I could finally make my way to the living world above. Not to live, but to be put to rest. I know from instinct—as a newborn knows to breathe on exiting the womb—that certain death, whatever that means, lies beyond those doors. Deep within my hollow gut, I know that I will melt away like the fine dust of the Gobi. And yet, I feel a burning desire to open the door that has kept me confined in this purgatory, that taunts me and keeps me prisoner to this fate.

With every ounce of energy I could summon, I made my way to the door, trudging across the tomb for what I hoped would be my last two hundred meters. The clatter of bone and leather against stone was a sound I was now accustomed to. As I neared the door, the golden phoenixes caught the flicker of the dim flames. I could almost hear the stone snakes that stood guard by the door hiss, “A crueler fate awaits”. I could swear that their eyes glimmered with more life than mine.

I summoned every fiber of muscle and ligament that grew on my bones to push open the short door, hardly befitting an Emperor’s entry or exit. I had hoped to see light as the doors parted, but I was met only with darkness from the cobbled passageway that lay beyond. In the yellow light from my torch, I saw the path littered by brittle bones still wrapped in their owner’s clothes, golden bracelets and pearl necklaces still adorning bony wrists.

I made my way through the pitiful grave. There was still no breeze against my tunic. Still no light. As I trudged forward through piles of bones in the narrow passageway, arrows whistled by, traps meant to deter tomb raiders. After two millennia, they struck their own emperor. They lodged in my chest and my arms. It made no difference. As I walked on, I found myself struck by more waves of arrows that covered my body. I did not bleed, and my flesh grew back, enveloping the arrowheads and claiming them as my own. And then I saw the door. An exit, finally!

Or so I thought.

Suddenly, the earth rumbled, and before my own eyes, the roof caved in, piling rock and sand and dust in my way to create an insurmountable, unmoving wall. Behind it, the door stood, unchallenged, forever sealed, and with it, I felt my own fate sealed forever. Entombed once again.

I limped back to my tomb, closed the doors, and attempted to once again butcher myself—one last desperate attempt. I tore at my leathery skin to expose the hollow inside me. The arrowheads clinked to the floor. But I was fated to keep standing, to regrow like weed.

But I am no more conflicted about choosing life, death, or what lies in between. To be turned to dust is all I wish for. It is perhaps only through death, absolute and consummate, that I will make my way to Mount Penglai.

This is my story. I leave behind this letter for whoever comes next, alive or undead. If you are reading this, you have made your way to the realm beyond the underworld. In doing so, you have freed a tormented soul. I thank you for this mercy. These are my final words and proof that your emperor endured unfathomable torment. I have lived more lives than historians can fathom, ruled more years of the underworld than any emperor before me and any after me, and repented for more years than I lived. I regret that there is only so much I can tell you, for I have more gold than I need, and lamentably less ink than I desire.

Your First Emperor,

Qin Shi Huangdi

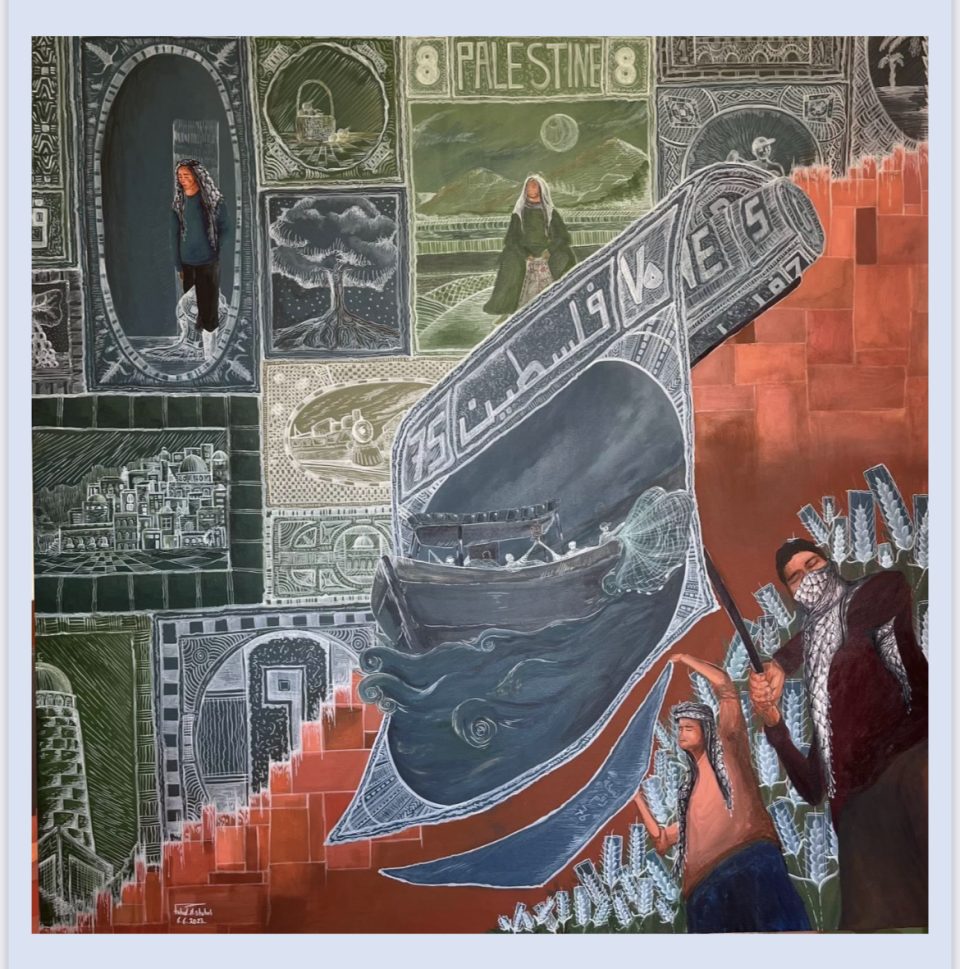

Painting Courtesy of Our Featured Artist Fahed Mohammed Shehab